Laura Pitt-Pulford, Michael Ball and Danielle de Niese in Aspects of Love. Photo by Johan Persson.

Laura Pitt-Pulford, Michael Ball and Danielle de Niese in Aspects of Love. Photo by Johan Persson.

ASPECTS OF LOVE

July 6, 2023

Lyric Theatre, London

There’s been quite a lot of hoo-ha about this new revival of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s 1989 musical, co-written with Don Black and Charles Hart, about love between the generations of one family. There seems to be quite an ick factor in particular about the attraction between two cousins, one much older than the other, with its implication of grooming in the #MeToo era.

And yes, the story – based on a 1955 novella by David Garnett – remains moderately shocking, with its uncle-and-nephew pair sharing one object of desire, and a mistress and aforementioned cousin revolving around this ménage à trois. But in truth, there’s nothing trickier here than you’d find in your average episode of EastEnders, and it’s not exactly shied away from in the lyrical themes.

In the nuanced hands of director Jonathan Kent, what Aspects offers today – besides a predictably show-stopping turn from Michael Ball as Uncle George – is a series of vignettes about the vicissitudes of that great motivator, love, collated as a chamber musical of elegance, beauty and somewhat serious intent.

Veteran opera designer John Macfarlane makes his first foray into West End musicals and his backdrops and artistic input lend the production much of its character and atmosphere, recreating 1960s Paris or the French countryside or a circus crowd with a painter’s instincts and an audience’s sensibilities.

Meanwhile, the voices are terrific. Ball sparkles, relishing his new role as the older man more than 30 years after playing the younger lead (and having the score neatly tweaked to give him back his most famous number, Love Changes Everything). But Jamie Bogyo as his nephew Alex matches him note for note in both singing and acting, and the pair work superbly together

Laura Pitt-Pulford sidesteps potential melodrama to create a fully-rounded Rose, the object of both their desires, while Danielle de Niese judges the mistress Giulietta perfectly, making it quite obvious why everyone – Rose included – is in thrall to her voluptuous, life-affirming character. Anna Unwin completes the quintet as the young cousin Jenny, playing her as old enough to understand her womanhood while retaining an appropriate air of innocence. Thanks to her, the ick is largely absent.

New orchestrations by Tom Kelly place a huge emphasis on five strings in Cat Beveridge’s 13-strong band, which occasionally strains to sound lush enough for Lloyd Webber’s score, but any suggestion that Love Changes Everything is the only real tune in this show is comprehensively demolished by both the songs and the arrangements, which come through crystal clear in Paul Groothuis’s impeccable sound design.

Jon Clark’s lighting, too, helps generate atmosphere and tension as Macfarlane’s flats swoop across the stage, with Douglas O’Connell’s video and projections providing just enough context to frame the upcoming scene.

It’s a beguiling and musically satisfying production that belies the opprobrium that has been heaped upon it to the point, mystifyingly, of advancing its early closure on August 19. Suffice it to say, the audience I was in disagreed.

July 6, 2023

Lyric Theatre, London

There’s been quite a lot of hoo-ha about this new revival of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s 1989 musical, co-written with Don Black and Charles Hart, about love between the generations of one family. There seems to be quite an ick factor in particular about the attraction between two cousins, one much older than the other, with its implication of grooming in the #MeToo era.

And yes, the story – based on a 1955 novella by David Garnett – remains moderately shocking, with its uncle-and-nephew pair sharing one object of desire, and a mistress and aforementioned cousin revolving around this ménage à trois. But in truth, there’s nothing trickier here than you’d find in your average episode of EastEnders, and it’s not exactly shied away from in the lyrical themes.

In the nuanced hands of director Jonathan Kent, what Aspects offers today – besides a predictably show-stopping turn from Michael Ball as Uncle George – is a series of vignettes about the vicissitudes of that great motivator, love, collated as a chamber musical of elegance, beauty and somewhat serious intent.

Veteran opera designer John Macfarlane makes his first foray into West End musicals and his backdrops and artistic input lend the production much of its character and atmosphere, recreating 1960s Paris or the French countryside or a circus crowd with a painter’s instincts and an audience’s sensibilities.

Meanwhile, the voices are terrific. Ball sparkles, relishing his new role as the older man more than 30 years after playing the younger lead (and having the score neatly tweaked to give him back his most famous number, Love Changes Everything). But Jamie Bogyo as his nephew Alex matches him note for note in both singing and acting, and the pair work superbly together

Laura Pitt-Pulford sidesteps potential melodrama to create a fully-rounded Rose, the object of both their desires, while Danielle de Niese judges the mistress Giulietta perfectly, making it quite obvious why everyone – Rose included – is in thrall to her voluptuous, life-affirming character. Anna Unwin completes the quintet as the young cousin Jenny, playing her as old enough to understand her womanhood while retaining an appropriate air of innocence. Thanks to her, the ick is largely absent.

New orchestrations by Tom Kelly place a huge emphasis on five strings in Cat Beveridge’s 13-strong band, which occasionally strains to sound lush enough for Lloyd Webber’s score, but any suggestion that Love Changes Everything is the only real tune in this show is comprehensively demolished by both the songs and the arrangements, which come through crystal clear in Paul Groothuis’s impeccable sound design.

Jon Clark’s lighting, too, helps generate atmosphere and tension as Macfarlane’s flats swoop across the stage, with Douglas O’Connell’s video and projections providing just enough context to frame the upcoming scene.

It’s a beguiling and musically satisfying production that belies the opprobrium that has been heaped upon it to the point, mystifyingly, of advancing its early closure on August 19. Suffice it to say, the audience I was in disagreed.

Sam Underwood and Natalie Dunne star in The Third Man. Photo by Manuel Harlan.

Sam Underwood and Natalie Dunne star in The Third Man. Photo by Manuel Harlan.

THE THIRD MAN

July 4, 2023

Menier Chocolate Factory, London

Carol Reed’s 1949 noir classic is frequently trotted out as possibly the best British film ever made, so anyone attempting to adapt it as a stage musical is always going to be up against the naysayers – even when those adapters are of the calibre on display here.

Musical veterans Don Black and Christopher Hampton have supplied words to a score by one of this country’s leading film and television composers, George Fenton, and the whole thing has been put on stage by Trevor Nunn, who once ran the RSC and has directed many of the world’s biggest musicals for decades.

The result, in the wonderfully claustrophobic Menier Chocolate Factory, is a moody, intense, noir musical with flashes of wit and cynicism that would have made original author Graham Greene proud. And while it might not rank up there with the finest work of any of its creators, it’s still a fine, atmospheric thriller with plenty to recommend it.

Fenton’s music is full of dark corners, using Anton Karas’s iconic zither theme from the film only obliquely and sparingly, but to great effect when it does seep in. One or two numbers – notably a couple of cabaret turns used to lighten the mood in each half – sit less comfortably with the overall tone, but it remains a textured and intriguing score.

Black and Hampton take the opportunity to expand on some of the ideas in Greene’s original novella, written as a treatment for the movie, thus making more of the homosexual undertones in the triumvirate of baddies attempting to conceal what really happened to mysterious racketeer Harry Lime in post-war Vienna. But the writers’ main focus is Holly Martins – the hack writer of westerns who comes to the ravaged city to find his old friend and ends up trammelled in a conspiracy of horror and death – and Anna Schmidt, the girl Lime has abandoned.

Here, and in the figure of Lime himself, the production reveals its secret weapons: Sam Underwood is terrific as the tortured Martins, Natalie Dunne does understated broken lover superbly, and Simon Bailey steals the show with a superb Harry Lime which channels the spirit of Orson Welles without ever attempting impersonation. The famous scene between Martins and Lime on the Ferris wheel at the Prater amusement park is beautifully delivered, weaving song into the well-known dialogue on a simple raised platform that becomes the ride thanks to Paul Farnsworth’s clever set and Emma Chapman’s sublime lighting.

This design pair have achieved the near impossible, recalling without mimicking the imagery of Reed’s landmark black-and-white film using largely monochromatic colour schemes and dramatic visual effects, and it works brilliantly. Tamara Saringer’s musical direction and nine-piece band, coupled with some layered orchestrations by another musicals veteran, Jason Carr, add still more to the classy mix, and under Nunn’s directorial hand the result is an accomplished refreshing of an old friend.

Altogether now: dum de-dum de-dummm de-dum…

July 4, 2023

Menier Chocolate Factory, London

Carol Reed’s 1949 noir classic is frequently trotted out as possibly the best British film ever made, so anyone attempting to adapt it as a stage musical is always going to be up against the naysayers – even when those adapters are of the calibre on display here.

Musical veterans Don Black and Christopher Hampton have supplied words to a score by one of this country’s leading film and television composers, George Fenton, and the whole thing has been put on stage by Trevor Nunn, who once ran the RSC and has directed many of the world’s biggest musicals for decades.

The result, in the wonderfully claustrophobic Menier Chocolate Factory, is a moody, intense, noir musical with flashes of wit and cynicism that would have made original author Graham Greene proud. And while it might not rank up there with the finest work of any of its creators, it’s still a fine, atmospheric thriller with plenty to recommend it.

Fenton’s music is full of dark corners, using Anton Karas’s iconic zither theme from the film only obliquely and sparingly, but to great effect when it does seep in. One or two numbers – notably a couple of cabaret turns used to lighten the mood in each half – sit less comfortably with the overall tone, but it remains a textured and intriguing score.

Black and Hampton take the opportunity to expand on some of the ideas in Greene’s original novella, written as a treatment for the movie, thus making more of the homosexual undertones in the triumvirate of baddies attempting to conceal what really happened to mysterious racketeer Harry Lime in post-war Vienna. But the writers’ main focus is Holly Martins – the hack writer of westerns who comes to the ravaged city to find his old friend and ends up trammelled in a conspiracy of horror and death – and Anna Schmidt, the girl Lime has abandoned.

Here, and in the figure of Lime himself, the production reveals its secret weapons: Sam Underwood is terrific as the tortured Martins, Natalie Dunne does understated broken lover superbly, and Simon Bailey steals the show with a superb Harry Lime which channels the spirit of Orson Welles without ever attempting impersonation. The famous scene between Martins and Lime on the Ferris wheel at the Prater amusement park is beautifully delivered, weaving song into the well-known dialogue on a simple raised platform that becomes the ride thanks to Paul Farnsworth’s clever set and Emma Chapman’s sublime lighting.

This design pair have achieved the near impossible, recalling without mimicking the imagery of Reed’s landmark black-and-white film using largely monochromatic colour schemes and dramatic visual effects, and it works brilliantly. Tamara Saringer’s musical direction and nine-piece band, coupled with some layered orchestrations by another musicals veteran, Jason Carr, add still more to the classy mix, and under Nunn’s directorial hand the result is an accomplished refreshing of an old friend.

Altogether now: dum de-dum de-dummm de-dum…

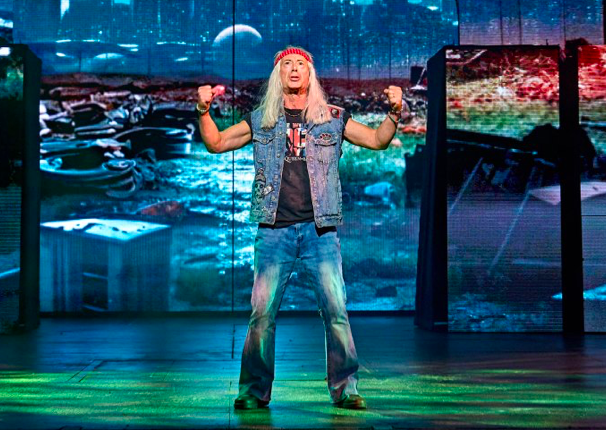

Ben Elton directs and stars in his own show, We Will Rock You. Photo by Manuel Harlan.

Ben Elton directs and stars in his own show, We Will Rock You. Photo by Manuel Harlan.

WE WILL ROCK YOU

July 3, 2023

Coliseum, London

It’s not often that members of the band get the top name check in a theatre review but axe heroes Nick Kendall and Nick Radcliffe deserve star billing for their astonishing recreations of Brian May’s iconic guitar solos in this revival of Ben Elton’s crowd-pleasing musical.

Of course, it helps to have Queen’s extraordinary back catalogue as your playground, but even so, the pair are truly exceptional. They and the rest of the band – Arlene McNaught, Neil Murray and Dave Cottrell – provide a stunning backbeat for the energetic power-show under the rock-solid musical direction of Stuart Morley.

First drafted more than 20 years ago and with a 12-year run at the Dominion Theatre under its belt, We Will Rock You proved the critics out of touch when its unabashed popularity with the public carried it from one record-breaking landmark to another. This new, state-of-the-art production, directed by and starring Elton himself for the first time in a theatre role, is no less imperious in its ambitions and achievements.

Yes, the story is inevitably contrived, with its dystopian future in which all music is carefully controlled by the megacorp GlobalSoft, and only the rebel Bohemians and their saviour Galileo Figaro can restore human creativity by rediscovering the long-lost recordings of four ancient mystics known as Queen. But Elton’s tongue is so firmly in his cheek that it’s almost surprising he can deliver his lines, and the shameless joy with which he contorts lyrics, gags and musical references in his quickfire script is utterly infectious.

He is brilliantly served by his cast, too, with Ian McIntosh outstandingly good as Galileo, his rock voice matching his acting chops in a tour-de-force performance. Brenda Edwards makes a chilling Killer Queen, with Lee Mead on top form relishing every delicious second of his underused villain turn as Khashoggi, while Christine Allado and Adrian Hansel make the most of their moment as rebels Meat and Brit.

A huge ensemble is impeccably drilled by choreographer Jacob Fearey, and the set and video design by Stufish Entertainment Architects are superb. But it’s the songs, supervised and orchestrated by Brian May and Roger Taylor themselves, that are the undoubted star of this show, even if Elton makes a fine attempt at stealing that top billing.

Its limited run at the Coliseum means it won’t be breaking the kind of records it did at the Dominion, but the audiences will be heading off humming into the night just as happily as they ever were.

July 3, 2023

Coliseum, London

It’s not often that members of the band get the top name check in a theatre review but axe heroes Nick Kendall and Nick Radcliffe deserve star billing for their astonishing recreations of Brian May’s iconic guitar solos in this revival of Ben Elton’s crowd-pleasing musical.

Of course, it helps to have Queen’s extraordinary back catalogue as your playground, but even so, the pair are truly exceptional. They and the rest of the band – Arlene McNaught, Neil Murray and Dave Cottrell – provide a stunning backbeat for the energetic power-show under the rock-solid musical direction of Stuart Morley.

First drafted more than 20 years ago and with a 12-year run at the Dominion Theatre under its belt, We Will Rock You proved the critics out of touch when its unabashed popularity with the public carried it from one record-breaking landmark to another. This new, state-of-the-art production, directed by and starring Elton himself for the first time in a theatre role, is no less imperious in its ambitions and achievements.

Yes, the story is inevitably contrived, with its dystopian future in which all music is carefully controlled by the megacorp GlobalSoft, and only the rebel Bohemians and their saviour Galileo Figaro can restore human creativity by rediscovering the long-lost recordings of four ancient mystics known as Queen. But Elton’s tongue is so firmly in his cheek that it’s almost surprising he can deliver his lines, and the shameless joy with which he contorts lyrics, gags and musical references in his quickfire script is utterly infectious.

He is brilliantly served by his cast, too, with Ian McIntosh outstandingly good as Galileo, his rock voice matching his acting chops in a tour-de-force performance. Brenda Edwards makes a chilling Killer Queen, with Lee Mead on top form relishing every delicious second of his underused villain turn as Khashoggi, while Christine Allado and Adrian Hansel make the most of their moment as rebels Meat and Brit.

A huge ensemble is impeccably drilled by choreographer Jacob Fearey, and the set and video design by Stufish Entertainment Architects are superb. But it’s the songs, supervised and orchestrated by Brian May and Roger Taylor themselves, that are the undoubted star of this show, even if Elton makes a fine attempt at stealing that top billing.

Its limited run at the Coliseum means it won’t be breaking the kind of records it did at the Dominion, but the audiences will be heading off humming into the night just as happily as they ever were.

From left, Cassidy Janson, Miriam-Teak Lee and Melanie La Barrie. Photo: Johan Persson

From left, Cassidy Janson, Miriam-Teak Lee and Melanie La Barrie. Photo: Johan Persson

& JULIET

October 18, 2021

Shaftesbury Theatre, London

At times like these, when we’ve all endured seemingly endless months of isolation, seclusion and misery, a lightning bolt of unadulterated joy can be just what we need. And in & Juliet, that’s just what you get.

Stitched together from the back catalogue of Swedish producer and songwriter Max Martin, it may not have an original score, but it’s got as much energy, cheekiness and sheer in-yer-face-ness as any of the artists he’s worked with – among them Katy Perry, Taylor Swift and Pink. If you’ve never heard of him, don’t worry: he’s pretty much a recluse, doesn’t give interviews and shuns the limelight, so you’re far from alone.

But you’ve undoubtedly heard his music. From Britney’s …Baby One More Time and Backstreet Boys’ I Want It That Way to Coldplay’s latest Higher Power and My Universe, he’s had a hand in some of the greatest hits of the last 25 years. In fact, only Lennon and McCartney have a better chart record.

The task of bringing some of these massive songs together in a musical was handed to Schitt’s Creek writer David West Read, and his genius idea was to attach them to an original story about Shakespeare trying to write Romeo and Juliet while his dissatisfied wife Anne Hathaway keeps getting in the way. The two worlds may seem miles apart, but the fusion works brilliantly.

I’m starting a campaign to jettison the phrase ‘jukebox musical’. While this one takes pre-existing songs from an extraordinary catalogue, it repurposes them in such a revolutionary way that they appear almost fresh-minted. I’d suggest ‘mixtape musical’, except that still doesn’t pay proper tribute to Read’s brilliance: not content with finding the right song for each moment, he cleverly reallocates individual lines – even words – to make them fit his narrative.

But the show’s wit and exuberance are only half the story. The other half is Luke Sheppard’s production, which fizzes and bounces along with irrepressible heart and fun from curtain up to the inevitable standing ovation. Miriam-Teak Lee plays Juliet from the point where Shakespeare’s famous play of star-cross’d lovers leaves off, and she makes the journey from sad teen to feisty feminist with drive and some belting vocal cords.

Oliver Tompsett and Cassidy Janson clash amiably as Will and Anne, but the strength of performances runs throughout the entire huge ensemble, with each street-dance move and tight harmony delivered with the same passion and commitment. Musical director Patrick Hurley commands a live pit band of power and subtlety and the music is, appropriately enough, front and centre.

For humour, uplifting delight and simple musical quality, can there be a better show currently running in the West End? If there is, then sign me up now…

October 18, 2021

Shaftesbury Theatre, London

At times like these, when we’ve all endured seemingly endless months of isolation, seclusion and misery, a lightning bolt of unadulterated joy can be just what we need. And in & Juliet, that’s just what you get.

Stitched together from the back catalogue of Swedish producer and songwriter Max Martin, it may not have an original score, but it’s got as much energy, cheekiness and sheer in-yer-face-ness as any of the artists he’s worked with – among them Katy Perry, Taylor Swift and Pink. If you’ve never heard of him, don’t worry: he’s pretty much a recluse, doesn’t give interviews and shuns the limelight, so you’re far from alone.

But you’ve undoubtedly heard his music. From Britney’s …Baby One More Time and Backstreet Boys’ I Want It That Way to Coldplay’s latest Higher Power and My Universe, he’s had a hand in some of the greatest hits of the last 25 years. In fact, only Lennon and McCartney have a better chart record.

The task of bringing some of these massive songs together in a musical was handed to Schitt’s Creek writer David West Read, and his genius idea was to attach them to an original story about Shakespeare trying to write Romeo and Juliet while his dissatisfied wife Anne Hathaway keeps getting in the way. The two worlds may seem miles apart, but the fusion works brilliantly.

I’m starting a campaign to jettison the phrase ‘jukebox musical’. While this one takes pre-existing songs from an extraordinary catalogue, it repurposes them in such a revolutionary way that they appear almost fresh-minted. I’d suggest ‘mixtape musical’, except that still doesn’t pay proper tribute to Read’s brilliance: not content with finding the right song for each moment, he cleverly reallocates individual lines – even words – to make them fit his narrative.

But the show’s wit and exuberance are only half the story. The other half is Luke Sheppard’s production, which fizzes and bounces along with irrepressible heart and fun from curtain up to the inevitable standing ovation. Miriam-Teak Lee plays Juliet from the point where Shakespeare’s famous play of star-cross’d lovers leaves off, and she makes the journey from sad teen to feisty feminist with drive and some belting vocal cords.

Oliver Tompsett and Cassidy Janson clash amiably as Will and Anne, but the strength of performances runs throughout the entire huge ensemble, with each street-dance move and tight harmony delivered with the same passion and commitment. Musical director Patrick Hurley commands a live pit band of power and subtlety and the music is, appropriately enough, front and centre.

For humour, uplifting delight and simple musical quality, can there be a better show currently running in the West End? If there is, then sign me up now…

Ben Miles as Cromwell and Tony Turner as Wolsey. Photo: Mark Brenner/RSC

Ben Miles as Cromwell and Tony Turner as Wolsey. Photo: Mark Brenner/RSC

THE MIRROR AND THE LIGHT

October 17, 2021

Gielgud Theatre, London, until Saturday, January 23, 2022

The first two instalments of Hilary Mantel’s Booker prize-winning Wolf Hall trilogy about Thomas Cromwell were produced initially in Stratford-upon-Avon, on the RSC’s thrust Swan stage. Written by master adapter Mike Poulton, they told the dramatic tale of Cromwell’s meteoric and unlikely rise from Putney blacksmith’s son to Henry VIII’s chief courtier, via the patronage of Cardinal Wolsey.

For the last of the trio, Stratford, the thrust presentation and Poulton have all been jettisoned – and each decision has brought something of a down side to the production.

The RSC’s home crowd in the Midlands will undoubtedly feel cheated to have been denied first sight of the final episode, given that the stage version evolved and matured there. The intimacy of the thrust configuration lent an immediacy and co-conspiratorial nature to the intrigues of the Tudor hierarchy which the caverns of a proscenium-arch West End house can’t hope to match.

And whatever the reasons behind ditching a bona fide playwright in favour of this adaptation by Mantel herself and lead actor Ben Miles, The Mirror and the Light lacks the dramatic engineering of a playwright’s hand that the first two instalments had in spades.

That’s not to say there isn’t much to enjoy about the production, with plenty of Machiavellian machinations and dangerous deviousness and a clearly-told historical narrative. What seems to be missing is the emotional punch and dramatic action. Instead, we get scene after scene of plotting aristocrats, ambitious ambassadors and self-serving bureaucrats all trying to better one another and avoid the – literal – chop.

The performances are strong, with Miles and Nathaniel Parker trading blows entertainingly as Cromwell and his volatile monarch respectively. Nicholas Woodeson is supremely unpleasant as the Duke of Norfolk, hell-bent on bringing Cromwell down, and Liam Smith offers some edgy light relief as Cromwell’s long-dead and abusive father Walter. Even the ghost of Wolsey (Tony Turner) gets in amusingly on the act, offering some belated hindsight with the benefit of historical distance.

But it’s disappointing, too, that the women should get such short shrift from a story in which the politics revolves chiefly around them: out of a company of more than 20, fewer than a third are women, and most of them are bit players.

It’s a well-dressed, elegantly-staged production but – rather like the third book, which missed out on the Booker shortlist after the first two won it – it doesn’t quite carry the same heft as its predecessors.

October 17, 2021

Gielgud Theatre, London, until Saturday, January 23, 2022

The first two instalments of Hilary Mantel’s Booker prize-winning Wolf Hall trilogy about Thomas Cromwell were produced initially in Stratford-upon-Avon, on the RSC’s thrust Swan stage. Written by master adapter Mike Poulton, they told the dramatic tale of Cromwell’s meteoric and unlikely rise from Putney blacksmith’s son to Henry VIII’s chief courtier, via the patronage of Cardinal Wolsey.

For the last of the trio, Stratford, the thrust presentation and Poulton have all been jettisoned – and each decision has brought something of a down side to the production.

The RSC’s home crowd in the Midlands will undoubtedly feel cheated to have been denied first sight of the final episode, given that the stage version evolved and matured there. The intimacy of the thrust configuration lent an immediacy and co-conspiratorial nature to the intrigues of the Tudor hierarchy which the caverns of a proscenium-arch West End house can’t hope to match.

And whatever the reasons behind ditching a bona fide playwright in favour of this adaptation by Mantel herself and lead actor Ben Miles, The Mirror and the Light lacks the dramatic engineering of a playwright’s hand that the first two instalments had in spades.

That’s not to say there isn’t much to enjoy about the production, with plenty of Machiavellian machinations and dangerous deviousness and a clearly-told historical narrative. What seems to be missing is the emotional punch and dramatic action. Instead, we get scene after scene of plotting aristocrats, ambitious ambassadors and self-serving bureaucrats all trying to better one another and avoid the – literal – chop.

The performances are strong, with Miles and Nathaniel Parker trading blows entertainingly as Cromwell and his volatile monarch respectively. Nicholas Woodeson is supremely unpleasant as the Duke of Norfolk, hell-bent on bringing Cromwell down, and Liam Smith offers some edgy light relief as Cromwell’s long-dead and abusive father Walter. Even the ghost of Wolsey (Tony Turner) gets in amusingly on the act, offering some belated hindsight with the benefit of historical distance.

But it’s disappointing, too, that the women should get such short shrift from a story in which the politics revolves chiefly around them: out of a company of more than 20, fewer than a third are women, and most of them are bit players.

It’s a well-dressed, elegantly-staged production but – rather like the third book, which missed out on the Booker shortlist after the first two won it – it doesn’t quite carry the same heft as its predecessors.

LEOPOLDSTADT

October 16, 2021

Wyndham’s Theatre, London, until Saturday, October 30

Tom Stoppard’s latest epic, revived after Covid restrictions were eased this summer, has all the hallmarks of one of his greater pieces. It’s huge, crammed with ideas and – largely thanks to its subject matter – engages the emotions as well as the brain. While this may not always be the case in some of Stoppard’s more intellectual work, Leopoldstadt aims for the heart as well as the head.

The narrative follows the fortunes of one family in Vienna from the turn of the 20th century to the years after the Second World War, tracing the gradual disintegration of order and humanity through a series of vividly-constructed vignettes. Each generation learns the lessons of its predecessors, some through memories of the past, others through the realities of the present. And all the while the spectre of the Holocaust hangs over proceedings like a malignant predator.

There’s been much discussion about just how autobiographical the play is. Stoppard’s Jewish Czech family fled the country when he was a baby and he subsequently took the surname – and nationality – of his English stepfather. Similar, though not identical, events happen to one of the characters in the play. But in a sense, the question is academic: this family stands for the many millions of Jewish Europeans who endured oppression almost beyond imagination.

The embodiment of the atrocities in one clearly-drawn family is a triumph, and Stoppard makes each of the many characters more than a cipher for their respective ideas: Freudian philosophy, number theory, the evolution of classical music all make significant appearances but never overwhelm the simple story at the centre of the play.

Director Patrick Marber’s beautifully elegant production, designed by Richard Hudson (sets) and Brigitte Reiffenstuel (costumes), uses the huge family table, a grand piano and a portrait to provide the central imagery, cleverly echoing the collapse of the family – and its beloved nation – alongside evocative black-and-white photographs projected between scenes.

Across the vast cast, the performances are uniformly excellent, with Faye Castelow and Aidan McArdle anchoring the family superbly across a span of more than 50 years, and the complex relationships never become confusing or a diversion from the relentless thrust of the story. It’s a grim and powerful reminder of a century that may have gone by, but as for the family in Vienna, there’s that dangerous warning that terrifying possibilities are never far away.

October 16, 2021

Wyndham’s Theatre, London, until Saturday, October 30

Tom Stoppard’s latest epic, revived after Covid restrictions were eased this summer, has all the hallmarks of one of his greater pieces. It’s huge, crammed with ideas and – largely thanks to its subject matter – engages the emotions as well as the brain. While this may not always be the case in some of Stoppard’s more intellectual work, Leopoldstadt aims for the heart as well as the head.

The narrative follows the fortunes of one family in Vienna from the turn of the 20th century to the years after the Second World War, tracing the gradual disintegration of order and humanity through a series of vividly-constructed vignettes. Each generation learns the lessons of its predecessors, some through memories of the past, others through the realities of the present. And all the while the spectre of the Holocaust hangs over proceedings like a malignant predator.

There’s been much discussion about just how autobiographical the play is. Stoppard’s Jewish Czech family fled the country when he was a baby and he subsequently took the surname – and nationality – of his English stepfather. Similar, though not identical, events happen to one of the characters in the play. But in a sense, the question is academic: this family stands for the many millions of Jewish Europeans who endured oppression almost beyond imagination.

The embodiment of the atrocities in one clearly-drawn family is a triumph, and Stoppard makes each of the many characters more than a cipher for their respective ideas: Freudian philosophy, number theory, the evolution of classical music all make significant appearances but never overwhelm the simple story at the centre of the play.

Director Patrick Marber’s beautifully elegant production, designed by Richard Hudson (sets) and Brigitte Reiffenstuel (costumes), uses the huge family table, a grand piano and a portrait to provide the central imagery, cleverly echoing the collapse of the family – and its beloved nation – alongside evocative black-and-white photographs projected between scenes.

Across the vast cast, the performances are uniformly excellent, with Faye Castelow and Aidan McArdle anchoring the family superbly across a span of more than 50 years, and the complex relationships never become confusing or a diversion from the relentless thrust of the story. It’s a grim and powerful reminder of a century that may have gone by, but as for the family in Vienna, there’s that dangerous warning that terrifying possibilities are never far away.

Ash Palmisciano, co-writer and star of The Ultimate Lad.

Ash Palmisciano, co-writer and star of The Ultimate Lad.

THE ULTIMATE LAD

* * * * *

March 15, 2020

The Crescent, Vaults Festival, Sunday, March 15, 2020

ANYBODY going through the traumatic process of transitioning – and living with the knowledge that their past could be exposed at any time – already has a battle on their hands. If you then co-write an autobiographical monologue about it and optimise the fame you’ve gained from a high-profile role on national television to bring it to a wider public, then you’re either barmy or unbelievably brave.

It takes just moments from Ash Palmisciano’s bounding on to the Vaults stage to realise that it’s the latter of the two. The Ultimate Lad is incredibly exposing for him as a performer, let alone as a person, and he has the audience in thrall from the outset as he offers considerably more than a glimpse into his astonishing journey to actor, soap star and man.

In case the name escapes you, he’s currently to be found on our television screens playing soapland’s first transgender character, Matty Barton, in Emmerdale. It’s a part he landed after originally going in to advise the programme on its intended storyline and getting asked back to audition for the role himself. Over the past 18 months he’s found himself an accidental trailblazer for the trans community and, as a result, a nominee for a diversity role model award.

But all of that was in the future when the events of The Ultimate Lad happened. With the guiding hand of co-writer and director Jon Brittain, Palmisciano has constructed a narrative that rides an emotional rollercoaster from hilarious highs to deep, dark lows, tapping into every fear of the outsider and resonating with anyone who’s felt trapped in their situation. That he makes it so funny in the telling is a tribute to both his skill as an actor and his extraordinary willingness to open his heart.

This is personal testimony as compelling drama, and Palmisciano pulls it off brilliantly. Every character he relates – from his Australian work supervisor to his faintly baffled father – is beautifully drawn and thoroughly real, and there’s an added punch of poignancy about knowing that it’s all based on lived experience.

A narrative as powerful as this, so intelligently constructed and honestly delivered, deserves to be compulsory viewing for anyone who’s ever wondered about the LGBTQ+ community. And even if you haven’t, it’s a blisteringly good drama on its own terms, and cries out to be discovered by a much wider audience.

* * * * *

March 15, 2020

The Crescent, Vaults Festival, Sunday, March 15, 2020

ANYBODY going through the traumatic process of transitioning – and living with the knowledge that their past could be exposed at any time – already has a battle on their hands. If you then co-write an autobiographical monologue about it and optimise the fame you’ve gained from a high-profile role on national television to bring it to a wider public, then you’re either barmy or unbelievably brave.

It takes just moments from Ash Palmisciano’s bounding on to the Vaults stage to realise that it’s the latter of the two. The Ultimate Lad is incredibly exposing for him as a performer, let alone as a person, and he has the audience in thrall from the outset as he offers considerably more than a glimpse into his astonishing journey to actor, soap star and man.

In case the name escapes you, he’s currently to be found on our television screens playing soapland’s first transgender character, Matty Barton, in Emmerdale. It’s a part he landed after originally going in to advise the programme on its intended storyline and getting asked back to audition for the role himself. Over the past 18 months he’s found himself an accidental trailblazer for the trans community and, as a result, a nominee for a diversity role model award.

But all of that was in the future when the events of The Ultimate Lad happened. With the guiding hand of co-writer and director Jon Brittain, Palmisciano has constructed a narrative that rides an emotional rollercoaster from hilarious highs to deep, dark lows, tapping into every fear of the outsider and resonating with anyone who’s felt trapped in their situation. That he makes it so funny in the telling is a tribute to both his skill as an actor and his extraordinary willingness to open his heart.

This is personal testimony as compelling drama, and Palmisciano pulls it off brilliantly. Every character he relates – from his Australian work supervisor to his faintly baffled father – is beautifully drawn and thoroughly real, and there’s an added punch of poignancy about knowing that it’s all based on lived experience.

A narrative as powerful as this, so intelligently constructed and honestly delivered, deserves to be compulsory viewing for anyone who’s ever wondered about the LGBTQ+ community. And even if you haven’t, it’s a blisteringly good drama on its own terms, and cries out to be discovered by a much wider audience.

BELLY UP

* * * *

February 23, 2020

The Forge, Vaults Festival, Sunday, February 23

There’s a play on at the National Theatre at the moment called The Welkin, about a woman in 18th century England who appeals for clemency from execution by claiming she’s pregnant – pleading the belly, as it was known. I haven’t seen it yet, but I can’t imagine it’s as much of a riotous romp as this blistering, hour-long feminist lesbian clarion call.

Writers Julia Grogan and Lydia Higman pull off the not unremarkable trick of addressing hideous iniquities against women, including some rather graphic detail about the penalties involved, with a tonal touch that constantly wavers on the periphery of absurdity while delivering consistently funny lines. Which naturally makes their underlying message all the more potent.

Grogan herself plays Liberty Whitley, the unjustly accused maidservant whose self-defence against the advances of her master provides no defence at all in court. The only way to save herself from the gallows – and be reunited with the object of her desire, her master’s betrothed, Phoebe – is to plead the belly. The only problem is, as a virginal lesbian, she’s not pregnant.

The ensuing chaotic caper, trying to find a willing sperm donor in Newgate Prison’s women’s ward while fighting a proto-feminist battle of the sexes in the process, is deftly handled in the witty and barbed script, and equally brilliantly executed on a tiny playing area by the versatile cast of five.

Apart from the no-nonsense Grogan, the ensemble play a wide and diverse range of characters, from upper-crust nincompoops to dim-witted jailers, all of them beautifully judged and seamlessly performed. Michael Bijok and Matthew Grainger’s double act as a pair of tarts with hearts is particularly entertaining, but there’s good work too from Anna Brindle and Annabel Wood completing the team.

Lauren Dickson directs with a clear-eyed sense of what works and what doesn’t, and there are some wonderful modern references and resonances, not least in the intelligent and hilarious use of music and dance. It’s unquestionably a show for today, despite its narrative from more than 200 years ago, and Liberty’s final rallying cry to the 21st century warriors who are carrying her torch is almost unnecessary: Belly Up’s message is clear and powerful and very, very funny.

* * * *

February 23, 2020

The Forge, Vaults Festival, Sunday, February 23

There’s a play on at the National Theatre at the moment called The Welkin, about a woman in 18th century England who appeals for clemency from execution by claiming she’s pregnant – pleading the belly, as it was known. I haven’t seen it yet, but I can’t imagine it’s as much of a riotous romp as this blistering, hour-long feminist lesbian clarion call.

Writers Julia Grogan and Lydia Higman pull off the not unremarkable trick of addressing hideous iniquities against women, including some rather graphic detail about the penalties involved, with a tonal touch that constantly wavers on the periphery of absurdity while delivering consistently funny lines. Which naturally makes their underlying message all the more potent.

Grogan herself plays Liberty Whitley, the unjustly accused maidservant whose self-defence against the advances of her master provides no defence at all in court. The only way to save herself from the gallows – and be reunited with the object of her desire, her master’s betrothed, Phoebe – is to plead the belly. The only problem is, as a virginal lesbian, she’s not pregnant.

The ensuing chaotic caper, trying to find a willing sperm donor in Newgate Prison’s women’s ward while fighting a proto-feminist battle of the sexes in the process, is deftly handled in the witty and barbed script, and equally brilliantly executed on a tiny playing area by the versatile cast of five.

Apart from the no-nonsense Grogan, the ensemble play a wide and diverse range of characters, from upper-crust nincompoops to dim-witted jailers, all of them beautifully judged and seamlessly performed. Michael Bijok and Matthew Grainger’s double act as a pair of tarts with hearts is particularly entertaining, but there’s good work too from Anna Brindle and Annabel Wood completing the team.

Lauren Dickson directs with a clear-eyed sense of what works and what doesn’t, and there are some wonderful modern references and resonances, not least in the intelligent and hilarious use of music and dance. It’s unquestionably a show for today, despite its narrative from more than 200 years ago, and Liberty’s final rallying cry to the 21st century warriors who are carrying her torch is almost unnecessary: Belly Up’s message is clear and powerful and very, very funny.

FALSETTOS

* * * *

September 5, 2019

The Other Palace until Saturday, November 23, 2019

If ever there was a triumph of delivery over content, then this first London production of the New York Jewish musical Falsettos is it. Everything about its production – the performances, the band, the direction – is so impeccable that review is rendered hardly necessary.

It’s unfortunate that so-called ‘Falsettogate’ has dogged the production with claims of cultural misappropriation because of the lack of any Jews in its construction. While it’s hard to argue with that, what is never in doubt is the quality of the performances that are on display in a tightly-knit sextet of adults and one starring turn from a child.

Essentially, Falsettos is a family comedy with a twist (or several). It focuses on Marvin, who leaves his wife and child for another man, Whizzer. The story plays with the quirky relationships between this group, plus the family’s psychiatrist Mendel, who becomes personally involved to add another layer of complexity. If I tell you that the opening number is called Four Jews in a Room Bitching, you’ll get some idea of the tone.

But while the tale is packed with cultural idiosyncrasies, comic songs and smart asides, it doesn’t quite have the lyrical, narrative or musical sharpness to work as a fully-rounded piece. When you learn it’s been cobbled together from three pre-existing one-act musicals, it makes more sense, but there’s something about the sudden gratuitous appearance of a lesbian couple next door at the start of Act Two, then the distinctly downbeat turn that things take, lurching tonally in a whole new direction, that undermines the bite which the show could deliver.

With those gripes out of the way, let’s return to those stunning performances. Daniel Boys holds things together as Marvin, a constantly neurotic, effervescent personality with vocal bravura to match his acting talents. Laura Pitt-Pulford is just as impressive as his ex-wife Trina, devastatingly funny and powerful in her first-act solo I’m Breaking Down.

Oliver Savile is almost too nice as Marvin’s love interest Whizzer, giving little hint of the characteristics that drive Marvin crazy, but he’s also in fine voice and has a twinkle in his eye. Joel Montague as the shrink gets to play it for laughs, and milks every opportunity from it in the process. In the performance I saw, Elliot Morris played Jason, the family’s young son who has to deal with the madness around him and somehow stay sane. Morris is utterly compelling, doing comedy, pathos and patter songs with equal verve and an alarming amount of confidence to go with his abilities.

The small band under MD Richard John generates a fabulous, controlled sound, and Tara Overfield-Wilkinson’s astute direction and choreography never interferes with the storytelling while adding just the right amount of pizzazz to a show that never flags in pace.

It may be mired in controversy off-stage, but the quality of the on-stage work is undeniable.

* * * *

September 5, 2019

The Other Palace until Saturday, November 23, 2019

If ever there was a triumph of delivery over content, then this first London production of the New York Jewish musical Falsettos is it. Everything about its production – the performances, the band, the direction – is so impeccable that review is rendered hardly necessary.

It’s unfortunate that so-called ‘Falsettogate’ has dogged the production with claims of cultural misappropriation because of the lack of any Jews in its construction. While it’s hard to argue with that, what is never in doubt is the quality of the performances that are on display in a tightly-knit sextet of adults and one starring turn from a child.

Essentially, Falsettos is a family comedy with a twist (or several). It focuses on Marvin, who leaves his wife and child for another man, Whizzer. The story plays with the quirky relationships between this group, plus the family’s psychiatrist Mendel, who becomes personally involved to add another layer of complexity. If I tell you that the opening number is called Four Jews in a Room Bitching, you’ll get some idea of the tone.

But while the tale is packed with cultural idiosyncrasies, comic songs and smart asides, it doesn’t quite have the lyrical, narrative or musical sharpness to work as a fully-rounded piece. When you learn it’s been cobbled together from three pre-existing one-act musicals, it makes more sense, but there’s something about the sudden gratuitous appearance of a lesbian couple next door at the start of Act Two, then the distinctly downbeat turn that things take, lurching tonally in a whole new direction, that undermines the bite which the show could deliver.

With those gripes out of the way, let’s return to those stunning performances. Daniel Boys holds things together as Marvin, a constantly neurotic, effervescent personality with vocal bravura to match his acting talents. Laura Pitt-Pulford is just as impressive as his ex-wife Trina, devastatingly funny and powerful in her first-act solo I’m Breaking Down.

Oliver Savile is almost too nice as Marvin’s love interest Whizzer, giving little hint of the characteristics that drive Marvin crazy, but he’s also in fine voice and has a twinkle in his eye. Joel Montague as the shrink gets to play it for laughs, and milks every opportunity from it in the process. In the performance I saw, Elliot Morris played Jason, the family’s young son who has to deal with the madness around him and somehow stay sane. Morris is utterly compelling, doing comedy, pathos and patter songs with equal verve and an alarming amount of confidence to go with his abilities.

The small band under MD Richard John generates a fabulous, controlled sound, and Tara Overfield-Wilkinson’s astute direction and choreography never interferes with the storytelling while adding just the right amount of pizzazz to a show that never flags in pace.

It may be mired in controversy off-stage, but the quality of the on-stage work is undeniable.

GUYS AND DOLLS

* * * * *

October 20, 2018

Royal Albert Hall, London, until Saturday, October 20, 2018

They’re never going to get away with this, are they? Stage one of the most thrilling, joyous and delightful productions of perhaps the world’s finest musical and then only give three performances? Never mind the anti-Brexit march nearby, there’ll be riots in Kensington if they don’t bring this beauty back.

Dazzling the echoing vaults of the Royal Albert Hall, Stephen Mear’s semi-staged version of Frank Loesser’s 1950 masterpiece has got everything going for it: there’s a band of more than 30 from the Royal Philharmonic Concert Orchestra under the capable baton of James McKeon, there’s an ensemble of surefooted hoofers giving their all to Mear’s stunning choreography, and there’s a list of headliners to make any musical theatre fan drool.

Top of that list is Adrian Lester – not, perhaps, the immediate first thought for Sky Masterson, but nailing the role brilliantly. Not since Ewan McGregor’s turn at the Picadilly back in 2005 has there been such a charismatic, charming and delectable Sky: the twinkle never leaves his eyes.

The leading ladies are on excellent form too, Lara Pulver’s acting chops supplementing her wonderful singing voice as Sister Sarah and cabaret star Meow Meow bringing authenticity and vulnerability to the role of Adelaide. Jason Manford holds up creditably as Nathan Detroit, adding to his increasingly extensive list of musical theatre turns, and if Paul Nicholas and Sharon D Clarke feel a little underused as two stalwarts of the New York mission where much of the action takes place, it’s no fault of theirs. Nicholas in particular offers a polished gem in his touching song More I Cannot Wish You.

The use of a narrator – an elegantly stylish Stephen Mangan – allows Mear to circumvent some of the staging problems, but the director never uses the ‘concert performance’ tag as an excuse for under-delivering. Indeed, the song-and-dance numbers are faultlessly executed and spectacular in scale, with every element serving the show. Clive Rowe’s impeccable rendition of Sit Down, You’re Rockin’ the Boat may be a showstopper, but no one performer is able to steal it.

Instead, this team effort hits the heights as a true ensemble piece and must surely get picked up by someone wanting to transfer it into the West End. Whether they’d be able to get ‘the band’ back together in quite such barnstorming fashion would be a tough call, but it’s got to be worth a try.

* * * * *

October 20, 2018

Royal Albert Hall, London, until Saturday, October 20, 2018

They’re never going to get away with this, are they? Stage one of the most thrilling, joyous and delightful productions of perhaps the world’s finest musical and then only give three performances? Never mind the anti-Brexit march nearby, there’ll be riots in Kensington if they don’t bring this beauty back.

Dazzling the echoing vaults of the Royal Albert Hall, Stephen Mear’s semi-staged version of Frank Loesser’s 1950 masterpiece has got everything going for it: there’s a band of more than 30 from the Royal Philharmonic Concert Orchestra under the capable baton of James McKeon, there’s an ensemble of surefooted hoofers giving their all to Mear’s stunning choreography, and there’s a list of headliners to make any musical theatre fan drool.

Top of that list is Adrian Lester – not, perhaps, the immediate first thought for Sky Masterson, but nailing the role brilliantly. Not since Ewan McGregor’s turn at the Picadilly back in 2005 has there been such a charismatic, charming and delectable Sky: the twinkle never leaves his eyes.

The leading ladies are on excellent form too, Lara Pulver’s acting chops supplementing her wonderful singing voice as Sister Sarah and cabaret star Meow Meow bringing authenticity and vulnerability to the role of Adelaide. Jason Manford holds up creditably as Nathan Detroit, adding to his increasingly extensive list of musical theatre turns, and if Paul Nicholas and Sharon D Clarke feel a little underused as two stalwarts of the New York mission where much of the action takes place, it’s no fault of theirs. Nicholas in particular offers a polished gem in his touching song More I Cannot Wish You.

The use of a narrator – an elegantly stylish Stephen Mangan – allows Mear to circumvent some of the staging problems, but the director never uses the ‘concert performance’ tag as an excuse for under-delivering. Indeed, the song-and-dance numbers are faultlessly executed and spectacular in scale, with every element serving the show. Clive Rowe’s impeccable rendition of Sit Down, You’re Rockin’ the Boat may be a showstopper, but no one performer is able to steal it.

Instead, this team effort hits the heights as a true ensemble piece and must surely get picked up by someone wanting to transfer it into the West End. Whether they’d be able to get ‘the band’ back together in quite such barnstorming fashion would be a tough call, but it’s got to be worth a try.

Striking: Bill Milner and Sheila Hancock as Harold and Maude.

Striking: Bill Milner and Sheila Hancock as Harold and Maude.

HAROLD AND MAUDE

* * * *

March 17, 2018

Charing Cross Theatre, London, until May 12, 2018

It was a curious, whimsical cult movie of the early 1970s. Subsequently its writer, Colin Higgins, re-engineered it as a curious, whimsical cult stage play, now perfectly suited to the inviting surroundings of London’s Charing Cross Theatre.

And while Sheila Hancock may be the star attraction (although she leaves the show on March 31), there’s so much more than her admittedly beguiling performance to recommend this striking and handsome production.

Director Thom Southerland exercises his customary sense of imagery and intensity – crucially without overwhelming the narrative or the acting – to deliver a piece that retains the oddball wackiness of its source material while making full use of the theatrical opportunities offered by Higgins’s beautifully crafted script.

Harold is the spoilt teenage rich kid dedicated to shocking his mother with increasingly realistic mock suicides. His penchant for attending strangers’ funerals launches him into chance acquaintanceship with the mysterious and decidedly unconventional septuagenarian Maude, an erstwhile Austrian countess whose impending 80th birthday sparks ruminative reminiscences alongside inspired insight.

Hancock is never less than mesmerising as the offbeat pensioner, lurching happily from wistful misty-eyed memories to down-to-earth pragmatism in the blink of an eye. But Bill Milner as the impenetrable teenager matches her line for line, scene for scene, making their integral relationship both believable and extremely poignant. And he never sees the ending coming, which makes it all the more powerful.

There’s a strong supporting cast of multi-instrumentalists too, supplying a humorous, talented Greek chorus of commentary by means of delicious harmonies, superb musicianship and entertaining ensemble acting. Indeed, Michael Bruce’s wonderfully playful score is one of the production’s greatest successes, woven seamlessly into the action yet adding a genuine extra dimension with its nuances, wit and tunefulness.

Francis O’Connor’s simple design allows the action to unfold breezily, but also evokes early 1970s America with the same effortlessness that suffuses every aspect of show. It’s charming, challenging and a masterclass in acting, and goes down as yet another delightful hit in the Southerland/Charing Cross catalogue.

* * * *

March 17, 2018

Charing Cross Theatre, London, until May 12, 2018

It was a curious, whimsical cult movie of the early 1970s. Subsequently its writer, Colin Higgins, re-engineered it as a curious, whimsical cult stage play, now perfectly suited to the inviting surroundings of London’s Charing Cross Theatre.

And while Sheila Hancock may be the star attraction (although she leaves the show on March 31), there’s so much more than her admittedly beguiling performance to recommend this striking and handsome production.

Director Thom Southerland exercises his customary sense of imagery and intensity – crucially without overwhelming the narrative or the acting – to deliver a piece that retains the oddball wackiness of its source material while making full use of the theatrical opportunities offered by Higgins’s beautifully crafted script.

Harold is the spoilt teenage rich kid dedicated to shocking his mother with increasingly realistic mock suicides. His penchant for attending strangers’ funerals launches him into chance acquaintanceship with the mysterious and decidedly unconventional septuagenarian Maude, an erstwhile Austrian countess whose impending 80th birthday sparks ruminative reminiscences alongside inspired insight.

Hancock is never less than mesmerising as the offbeat pensioner, lurching happily from wistful misty-eyed memories to down-to-earth pragmatism in the blink of an eye. But Bill Milner as the impenetrable teenager matches her line for line, scene for scene, making their integral relationship both believable and extremely poignant. And he never sees the ending coming, which makes it all the more powerful.

There’s a strong supporting cast of multi-instrumentalists too, supplying a humorous, talented Greek chorus of commentary by means of delicious harmonies, superb musicianship and entertaining ensemble acting. Indeed, Michael Bruce’s wonderfully playful score is one of the production’s greatest successes, woven seamlessly into the action yet adding a genuine extra dimension with its nuances, wit and tunefulness.

Francis O’Connor’s simple design allows the action to unfold breezily, but also evokes early 1970s America with the same effortlessness that suffuses every aspect of show. It’s charming, challenging and a masterclass in acting, and goes down as yet another delightful hit in the Southerland/Charing Cross catalogue.

GYPSY

* * * *

July 25, 2015

Savoy Theatre, London, until Saturday, November 28, 2015

OK, so I’m a bit late on the Imelda Staunton bandwagon, I realise that. But a stonking performance is still a stonking performance, wherever it falls in the show’s run. And whatever way you cut it, however far up you are in this most vertiginous of theatres, Imelda Staunton’s is unquestionably a stonking performance.

This production of Gypsy started life in Chichester, home of so many outstanding West End transfers of recent years, and its director Jonathan Kent also helmed Sweeney Todd to huge success along the same route with the same star. Jule Styne’s score for Gypsy may not have the subtlety of Stephen Sondheim’s demon barber, but with Mr S as his lyricist, there’s still plenty to enjoy.

Inevitably, it’s the big showstoppers – originally written for Ethel Merman – that prove most successful. Staunton’s belting but emotive voice captures all the power from songs such as Everything’s Coming Up Roses and Some People, and she’s never less than mesmerising in the role of Rose, the pushy showbiz mum living out her dreams through her two browbeaten daughters. One, of course, went on to become America’s best-known stripper, Gypsy Rose Lee, but in spite of the title, this show is not about her.

Staunton enjoys terrific support from Gemma Sutton and Lara Pulver as the girls, one all glitzy golden girl, the other timidity personified – at least until she discovers the attractions of fame. Peter Davison is touching and utterly believable as Herbie, the reluctant manager who becomes a father figure to the youngsters, and it’s all held together by a superb pit band under musical director Nicholas Skilbeck.

The rags-to-riches tale may feel a little well-worn, like the girls’ recycled frocks, but it’s completely unmissable thanks to its star turn. And with swathes of the upper levels rather forlornly empty, my advice would be to grab a ticket while you can. They’ll be talking about it for years.

* * * *

July 25, 2015

Savoy Theatre, London, until Saturday, November 28, 2015

OK, so I’m a bit late on the Imelda Staunton bandwagon, I realise that. But a stonking performance is still a stonking performance, wherever it falls in the show’s run. And whatever way you cut it, however far up you are in this most vertiginous of theatres, Imelda Staunton’s is unquestionably a stonking performance.

This production of Gypsy started life in Chichester, home of so many outstanding West End transfers of recent years, and its director Jonathan Kent also helmed Sweeney Todd to huge success along the same route with the same star. Jule Styne’s score for Gypsy may not have the subtlety of Stephen Sondheim’s demon barber, but with Mr S as his lyricist, there’s still plenty to enjoy.

Inevitably, it’s the big showstoppers – originally written for Ethel Merman – that prove most successful. Staunton’s belting but emotive voice captures all the power from songs such as Everything’s Coming Up Roses and Some People, and she’s never less than mesmerising in the role of Rose, the pushy showbiz mum living out her dreams through her two browbeaten daughters. One, of course, went on to become America’s best-known stripper, Gypsy Rose Lee, but in spite of the title, this show is not about her.

Staunton enjoys terrific support from Gemma Sutton and Lara Pulver as the girls, one all glitzy golden girl, the other timidity personified – at least until she discovers the attractions of fame. Peter Davison is touching and utterly believable as Herbie, the reluctant manager who becomes a father figure to the youngsters, and it’s all held together by a superb pit band under musical director Nicholas Skilbeck.

The rags-to-riches tale may feel a little well-worn, like the girls’ recycled frocks, but it’s completely unmissable thanks to its star turn. And with swathes of the upper levels rather forlornly empty, my advice would be to grab a ticket while you can. They’ll be talking about it for years.

MISS SAIGON

* * * * *

December 13, 2014

Prince Edward Theatre, London

IT’S probably heresy to whisper it, but the score of Miss Saigon is much stronger than that of Les Miserables. Claude-Michel Schonberg relies less on the bombast and overblown melodrama of his earlier work to deliver an intelligent, powerful and ultimately very moving composition with just the right mix of showiness and subtlety.

Cameron Mackintosh’s canny decision to revive the 25-year-old Vietnam War reinterpretation of Madam Butterfly pays off handsomely, with director Laurence Connor filling the stage with action and spectacle or drilling down to moments of high emotion as required.

American imports Jon Jon Briones as The Engineer and Eva Noblezada in her professional debut as Kim are both terrific. Briones imbues the seedy fixer with some humanity amid the greed and self-interest, and steals the show with his big production number The American Dream. Noblezada is touching, feisty and possessed of a glorious voice as the native whose life is ruined by the devastation of the invading GIs.

Niall Sheehy, meanwhile, understudying the role of the hapless young soldier Chris, proves well capable of the part, making the most of his solos and delivering a fine duet with Kim on The Last Night of the World.

The show is glossy, glitzy and glamorous, with a judicious helping of uncomfortable exploitation thrown in to highlight the politically contentious themes, and it makes for a performance of highly effective musical theatre. Whether it has the legs to match the seemingly never-ending run of its near neighbour Les Mis – as it properly deserves – remains to be seen.

* * * * *

December 13, 2014

Prince Edward Theatre, London

IT’S probably heresy to whisper it, but the score of Miss Saigon is much stronger than that of Les Miserables. Claude-Michel Schonberg relies less on the bombast and overblown melodrama of his earlier work to deliver an intelligent, powerful and ultimately very moving composition with just the right mix of showiness and subtlety.

Cameron Mackintosh’s canny decision to revive the 25-year-old Vietnam War reinterpretation of Madam Butterfly pays off handsomely, with director Laurence Connor filling the stage with action and spectacle or drilling down to moments of high emotion as required.

American imports Jon Jon Briones as The Engineer and Eva Noblezada in her professional debut as Kim are both terrific. Briones imbues the seedy fixer with some humanity amid the greed and self-interest, and steals the show with his big production number The American Dream. Noblezada is touching, feisty and possessed of a glorious voice as the native whose life is ruined by the devastation of the invading GIs.

Niall Sheehy, meanwhile, understudying the role of the hapless young soldier Chris, proves well capable of the part, making the most of his solos and delivering a fine duet with Kim on The Last Night of the World.

The show is glossy, glitzy and glamorous, with a judicious helping of uncomfortable exploitation thrown in to highlight the politically contentious themes, and it makes for a performance of highly effective musical theatre. Whether it has the legs to match the seemingly never-ending run of its near neighbour Les Mis – as it properly deserves – remains to be seen.

MONTY PYTHON LIVE (MOSTLY)

* * * * *

July 1, 2014

O2 Arena, London, until Sunday, July 20, 2014

Yes, by their own admission it’s a loving rip-off. Yes, they’ve freely confessed they’re doing it for the money. Yes, it’s an unashamed trip down memory lane with rose-tinted spectacles firmly in place. But for God’s sake, this is Monty Python live on stage!

Any lurking suspicions that beyond the age of 70 they might not quite be up to it, or that the fondly remembered sketches wouldn't stand the test of more than 40 years, are resoundingly blown away with a stunning production that more than warrants the scale of the venue and the price of the tickets.

This is truly vintage stuff, and yet still magically feels as fresh as it did when the Pythons first tentatively aired on BBC2. Somehow the five surviving members find a way to imbue the oft-recited lines with a modern, breathing life, and the enthusiastic cheers are as much at the genuine entertainment as at the happy recognition.

With Eric Idle directing and Arlene Philips choreographing, it’s a proper show, brilliantly and cleverly staged. The old favourite sketches are there, along with projections of Terry Gilliam’s iconic cartoons and occasional appearances from Graham Chapman, but there are also plenty of songs and big dance numbers from the back catalogue. Composer John du Prez leads a fantastic live band and on-stage ensemble in these impressive interludes between the comedy, and the pace of the three-hour show never lets up.

John Cleese appears to be fighting with a cold - and largely winning - while all five are firing on all cylinders in terms of their timing, repartee and sheer enjoyment of being together again in front of a wildly supportive audience.

If there was ever any doubt about the wisdom of this late-in-the-day reunion, it’s comprehensively shattered in a night of unadulterated joy.

* * * * *

July 1, 2014

O2 Arena, London, until Sunday, July 20, 2014

Yes, by their own admission it’s a loving rip-off. Yes, they’ve freely confessed they’re doing it for the money. Yes, it’s an unashamed trip down memory lane with rose-tinted spectacles firmly in place. But for God’s sake, this is Monty Python live on stage!

Any lurking suspicions that beyond the age of 70 they might not quite be up to it, or that the fondly remembered sketches wouldn't stand the test of more than 40 years, are resoundingly blown away with a stunning production that more than warrants the scale of the venue and the price of the tickets.

This is truly vintage stuff, and yet still magically feels as fresh as it did when the Pythons first tentatively aired on BBC2. Somehow the five surviving members find a way to imbue the oft-recited lines with a modern, breathing life, and the enthusiastic cheers are as much at the genuine entertainment as at the happy recognition.

With Eric Idle directing and Arlene Philips choreographing, it’s a proper show, brilliantly and cleverly staged. The old favourite sketches are there, along with projections of Terry Gilliam’s iconic cartoons and occasional appearances from Graham Chapman, but there are also plenty of songs and big dance numbers from the back catalogue. Composer John du Prez leads a fantastic live band and on-stage ensemble in these impressive interludes between the comedy, and the pace of the three-hour show never lets up.

John Cleese appears to be fighting with a cold - and largely winning - while all five are firing on all cylinders in terms of their timing, repartee and sheer enjoyment of being together again in front of a wildly supportive audience.

If there was ever any doubt about the wisdom of this late-in-the-day reunion, it’s comprehensively shattered in a night of unadulterated joy.