Four wealthy entrepreneurs on a Pacific island in Love's Labour's Lost. Photo by Johan Persson.

Four wealthy entrepreneurs on a Pacific island in Love's Labour's Lost. Photo by Johan Persson.

LOVE’S LABOUR’S LOST

April 18, 2024

RSC, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, May 18, 2024

“A jest’s prosperity lies in the ear of him that hears it.” So says one of the characters in Shakespeare’s knockabout comedy Love’s Labour’s Lost, which sees four lads struggling to keep to their vow of three years’ monastic existence after the arrival on the scene of four lovable ladies.

It's down to you, then, as an audience member. As one of Will’s more obscure, not to say obtuse, offerings, this is a curious choice as the curtain-raiser on the joint artistic directorship of Tamara Harvey and Daniel Evans, who have been in post almost a year but whose programming is only now coming on-stream.

Neither directs here, handing the reins instead to RSC debutante Emily Burns, whose recent tour of Macbeth with Ralph Fiennes and Indira Varma couched a sturdy production in some vivid modern-day trappings. She pulls off a similar trick here, locating the play on a private Pacific island and introducing the four lads as wealthy young entrepreneurs looking for a paradise escape.

The setting is sumptuous, thanks in no small part to Joanna Scotcher’s extraordinary set, a giant revolve housing the entrance to a swanky Tracy Island-type hideaway, two sweeping staircases and a couple of life-size palm trees. With additional square footage offered by the apron stage, the space transforms into a tennis court, a spa and even, in one inspired scene, a golf course.

The performances tend towards the epic too, with an over-the-top comedy Spaniard in the shape of Jack Bardoe’s Don Armado, an urbane and verbose Tony Gardner as Holofernes and, on shore leave from his role in Our Flag Means Death, a spiky and enjoyable Nathan Foad in the tricky role of the clown Costard. Meanwhile, Luke Thompson’s Berowne is grounded and highly watchable, with Ioanna Kimbook providing a three-dimensional foil to his lovelorn suitor.

It’s notable that all bar two of the cast are also newbies to the RSC, and it will be interesting to see if the Harvey-Evans axis continues to bring in creative colleagues from their past lives. But there’s some RSC continuity in the form of veteran Paul Englishby’s delightful Hawaiian-inspired music, which runs as a thread through the whole production.

Ultimately, the play relies heavily on some fairly turgid wordplay and a lot of references that were relevant in Shakespeare’s day – which might explain why it isn’t often done. Some judicious pruning in both these regards wouldn’t have gone amiss, also helping to trim the excessive three-hour running time, and while the physical comedy and nuance-free farce are always a winner with audiences, they do feel as if they’re stretched a bit thin at times.

It’s a big, brash, busy production with only a short run, so maybe there’s value in its rarity as well as its broad laughs. It may not offer much in the way of clues about the RSC’s forthcoming menu, but as an aperitif it has plenty of breezy appeal.

April 18, 2024

RSC, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, May 18, 2024

“A jest’s prosperity lies in the ear of him that hears it.” So says one of the characters in Shakespeare’s knockabout comedy Love’s Labour’s Lost, which sees four lads struggling to keep to their vow of three years’ monastic existence after the arrival on the scene of four lovable ladies.

It's down to you, then, as an audience member. As one of Will’s more obscure, not to say obtuse, offerings, this is a curious choice as the curtain-raiser on the joint artistic directorship of Tamara Harvey and Daniel Evans, who have been in post almost a year but whose programming is only now coming on-stream.

Neither directs here, handing the reins instead to RSC debutante Emily Burns, whose recent tour of Macbeth with Ralph Fiennes and Indira Varma couched a sturdy production in some vivid modern-day trappings. She pulls off a similar trick here, locating the play on a private Pacific island and introducing the four lads as wealthy young entrepreneurs looking for a paradise escape.

The setting is sumptuous, thanks in no small part to Joanna Scotcher’s extraordinary set, a giant revolve housing the entrance to a swanky Tracy Island-type hideaway, two sweeping staircases and a couple of life-size palm trees. With additional square footage offered by the apron stage, the space transforms into a tennis court, a spa and even, in one inspired scene, a golf course.

The performances tend towards the epic too, with an over-the-top comedy Spaniard in the shape of Jack Bardoe’s Don Armado, an urbane and verbose Tony Gardner as Holofernes and, on shore leave from his role in Our Flag Means Death, a spiky and enjoyable Nathan Foad in the tricky role of the clown Costard. Meanwhile, Luke Thompson’s Berowne is grounded and highly watchable, with Ioanna Kimbook providing a three-dimensional foil to his lovelorn suitor.

It’s notable that all bar two of the cast are also newbies to the RSC, and it will be interesting to see if the Harvey-Evans axis continues to bring in creative colleagues from their past lives. But there’s some RSC continuity in the form of veteran Paul Englishby’s delightful Hawaiian-inspired music, which runs as a thread through the whole production.

Ultimately, the play relies heavily on some fairly turgid wordplay and a lot of references that were relevant in Shakespeare’s day – which might explain why it isn’t often done. Some judicious pruning in both these regards wouldn’t have gone amiss, also helping to trim the excessive three-hour running time, and while the physical comedy and nuance-free farce are always a winner with audiences, they do feel as if they’re stretched a bit thin at times.

It’s a big, brash, busy production with only a short run, so maybe there’s value in its rarity as well as its broad laughs. It may not offer much in the way of clues about the RSC’s forthcoming menu, but as an aperitif it has plenty of breezy appeal.

Samuel Barnett and Victoria Yeates as Ben and Imo. Photo by Ellie Kurttz.

Samuel Barnett and Victoria Yeates as Ben and Imo. Photo by Ellie Kurttz.

BEN AND IMO

February 29, 2024

RSC, The Swan, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, April 6, 2024

There are countless examples across the history of the arts of so-called geniuses behaving monstrously, yet being forgiven and remaining beloved because their extraordinary gifts somehow bestow immunity upon them. From Mozart’s arrogant petulance to Wagner’s antisemitism, the work is often hard to separate from the creator.

The conflation of artist with their art is just as virulent today – perhaps more so, thanks to the ubiquity of social media – meaning that Johnny Depp’s personal life has made him difficult to employ in Hollywood, while JK Rowling continues to prompt boycotts by former Harry Potter fans with her anti-trans posturing.

All of this and more is the tricky subject of Mark Ravenhill’s two-hander play Ben and Imo, which turns the spotlight on the pre-eminent 20th century British composer Benjamin Britten and, in particular, his appalling relationship with Imogen Holst, daughter of Planets composer Gustav and Britten’s assistant in the composition and preparation of the 1953 Coronation opera Gloriana.

Just how much leeway a titan of the artistic world should be granted is a fascinating, intractable question that Ravenhill teases out without ever coming to a conclusion. So we are exposed to Britten goading, haranguing, manipulating and screaming at Imogen – no slouch in the composition stakes herself but willing to subsume her own creativity solely in order to enable Britten’s. He’s bitchy, vicious and, above all, cruel, yet she continues to tolerate his childish outbursts and emotional stuntedness for the sake of the end result, the music.

Samuel Barnett and Victoria Yeates relentlessly circle each other, metaphorically and literally on Soutra Gilmour’s piano-dominated revolving set, sizing each other up, testing each other’s boundaries and wrangling the best possible work out of the chaos of their maladjusted partnership. There’s plenty of light and shade to match the east coast seasons as nine intense months pass between Imo’s arrival and the impending opening of the opera, and the two players deliver top-notch performances.

But there’s a notable hole in the shape of Ben’s life partner and muse, the tenor Peter Pears, for whom he wrote most of his leading roles and whose absence here makes the set-up feel lopsided, like a tripod with a missing leg. There’s also been a clear decision not to engage with posthumous suggestions of Britten’s latent paedophilia and focus instead on the maelstrom of monstrosity that is apparently a necessary component of creative genius.

In her final contribution as RSC interim artistic director before the new season launches under Tamara Harvey and Daniel Evans, Erica Whyman directs, delineating and powerfully dramatising the highs and lows in the to-and-fro dialogue and giving a new life to Ravenhill’s 2013 radio play, reworked a decade on for the Swan stage.

And if we’re still no closer to understanding why brilliant artists can’t be pleasant people – or at least functioning adults – instead of tortured monsters, we can at least hop on for a rollercoaster ride around the creation of an important work of art.

February 29, 2024

RSC, The Swan, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, April 6, 2024

There are countless examples across the history of the arts of so-called geniuses behaving monstrously, yet being forgiven and remaining beloved because their extraordinary gifts somehow bestow immunity upon them. From Mozart’s arrogant petulance to Wagner’s antisemitism, the work is often hard to separate from the creator.

The conflation of artist with their art is just as virulent today – perhaps more so, thanks to the ubiquity of social media – meaning that Johnny Depp’s personal life has made him difficult to employ in Hollywood, while JK Rowling continues to prompt boycotts by former Harry Potter fans with her anti-trans posturing.

All of this and more is the tricky subject of Mark Ravenhill’s two-hander play Ben and Imo, which turns the spotlight on the pre-eminent 20th century British composer Benjamin Britten and, in particular, his appalling relationship with Imogen Holst, daughter of Planets composer Gustav and Britten’s assistant in the composition and preparation of the 1953 Coronation opera Gloriana.

Just how much leeway a titan of the artistic world should be granted is a fascinating, intractable question that Ravenhill teases out without ever coming to a conclusion. So we are exposed to Britten goading, haranguing, manipulating and screaming at Imogen – no slouch in the composition stakes herself but willing to subsume her own creativity solely in order to enable Britten’s. He’s bitchy, vicious and, above all, cruel, yet she continues to tolerate his childish outbursts and emotional stuntedness for the sake of the end result, the music.

Samuel Barnett and Victoria Yeates relentlessly circle each other, metaphorically and literally on Soutra Gilmour’s piano-dominated revolving set, sizing each other up, testing each other’s boundaries and wrangling the best possible work out of the chaos of their maladjusted partnership. There’s plenty of light and shade to match the east coast seasons as nine intense months pass between Imo’s arrival and the impending opening of the opera, and the two players deliver top-notch performances.

But there’s a notable hole in the shape of Ben’s life partner and muse, the tenor Peter Pears, for whom he wrote most of his leading roles and whose absence here makes the set-up feel lopsided, like a tripod with a missing leg. There’s also been a clear decision not to engage with posthumous suggestions of Britten’s latent paedophilia and focus instead on the maelstrom of monstrosity that is apparently a necessary component of creative genius.

In her final contribution as RSC interim artistic director before the new season launches under Tamara Harvey and Daniel Evans, Erica Whyman directs, delineating and powerfully dramatising the highs and lows in the to-and-fro dialogue and giving a new life to Ravenhill’s 2013 radio play, reworked a decade on for the Swan stage.

And if we’re still no closer to understanding why brilliant artists can’t be pleasant people – or at least functioning adults – instead of tortured monsters, we can at least hop on for a rollercoaster ride around the creation of an important work of art.

Madeleine Mantock and Tom Varey as Agnes and Will in Hamnet. Photo by Manuel Harlan.

Madeleine Mantock and Tom Varey as Agnes and Will in Hamnet. Photo by Manuel Harlan.

HAMNET

April 12, 2023

RSC, Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until June 17, 2023

It’s probably been anticipated with as much fervour as the latest play by that young upstart Shakespeare. Lolita Chakrabarti’s adaptation of Maggie O’Farrell’s bestselling novel reimagining the lives and relationships of Will, Anne and their children has already sold out in Stratford and is transferring to London’s Garrick Theatre in the autumn.

Directed by acting artistic director Erica Whyman, the RSC picked this show to reopen its remodelled Swan Theatre, with new seats (featuring arms, no less) and a shortened stage. Its wood and crimson upholstery are as cosy and welcoming as they always were, with a bit of added comfort.

With its pedigree and literary antecedents, Hamnet is a solid, reliable seller. This is the theatre which, pre-pandemic, gave us a line of classy book adaptations, from Robert Harris’s Imperium to Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall, and this latest addition to the repertoire fits in perfectly to the roll call. It may not be as epic, as moving or as historically intriguing, but it’s got plenty to offer in the way of warmth and wit.

Chakrabarti condenses O’Farrell’s dense narrative into just over a couple of hours, filleting the story to focus on Anne Hathaway – here provocatively renamed Agnes as a symbol of reclaiming her identity from the imagined versions of four centuries of historians. The first half is all plot, with a succession of vignettes culminating in the birth of the Shakespeares’ eponymous son, and it gallops along beside some brisk furniture removal by the 16-strong cast.

Things really get interesting in the second half, though, when Madeleine Mantock’s Agnes is put through the wringer by her children’s various illnesses and the absence of her gallivanting playwright husband, played with panache by Tom Varey. Mantock holds the piece together superbly, leaping between eras and emotions with calm assurance and tugging at the heartstrings along the way.

Tom Piper’s simplistic design allows the theatre itself to do a lot of the heavy lifting, which will make its proscenium-arch transfer challenging, but there are times when things get overly fussy and busy to the detriment of the storytelling – a charge that can also be laid at some of the performances.

But the overall effect is one of considerable care, charm and concern to give voice to some of the lesser-known players in the Shakespeare history, positing a plausible alternative to the accepted version of events – which, as O’Farrell has pointed out, is just as much guesswork as her interpretation.

It’s a good-looking show that aims to make something theatrical out of a prize-winning historical novel. It may not always hit the mark but it’s a bold and worthy attempt.

April 12, 2023

RSC, Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until June 17, 2023

It’s probably been anticipated with as much fervour as the latest play by that young upstart Shakespeare. Lolita Chakrabarti’s adaptation of Maggie O’Farrell’s bestselling novel reimagining the lives and relationships of Will, Anne and their children has already sold out in Stratford and is transferring to London’s Garrick Theatre in the autumn.

Directed by acting artistic director Erica Whyman, the RSC picked this show to reopen its remodelled Swan Theatre, with new seats (featuring arms, no less) and a shortened stage. Its wood and crimson upholstery are as cosy and welcoming as they always were, with a bit of added comfort.

With its pedigree and literary antecedents, Hamnet is a solid, reliable seller. This is the theatre which, pre-pandemic, gave us a line of classy book adaptations, from Robert Harris’s Imperium to Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall, and this latest addition to the repertoire fits in perfectly to the roll call. It may not be as epic, as moving or as historically intriguing, but it’s got plenty to offer in the way of warmth and wit.

Chakrabarti condenses O’Farrell’s dense narrative into just over a couple of hours, filleting the story to focus on Anne Hathaway – here provocatively renamed Agnes as a symbol of reclaiming her identity from the imagined versions of four centuries of historians. The first half is all plot, with a succession of vignettes culminating in the birth of the Shakespeares’ eponymous son, and it gallops along beside some brisk furniture removal by the 16-strong cast.

Things really get interesting in the second half, though, when Madeleine Mantock’s Agnes is put through the wringer by her children’s various illnesses and the absence of her gallivanting playwright husband, played with panache by Tom Varey. Mantock holds the piece together superbly, leaping between eras and emotions with calm assurance and tugging at the heartstrings along the way.

Tom Piper’s simplistic design allows the theatre itself to do a lot of the heavy lifting, which will make its proscenium-arch transfer challenging, but there are times when things get overly fussy and busy to the detriment of the storytelling – a charge that can also be laid at some of the performances.

But the overall effect is one of considerable care, charm and concern to give voice to some of the lesser-known players in the Shakespeare history, positing a plausible alternative to the accepted version of events – which, as O’Farrell has pointed out, is just as much guesswork as her interpretation.

It’s a good-looking show that aims to make something theatrical out of a prize-winning historical novel. It may not always hit the mark but it’s a bold and worthy attempt.

The cast of Roy Alexander Weise's new RSC production of Much Ado About Nothing. Photo by Ikin Yum.

The cast of Roy Alexander Weise's new RSC production of Much Ado About Nothing. Photo by Ikin Yum.

MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING

February 18, 2022

RSC, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon

Roy Alexander Weise directs an Afrofuturist production of one of Shakespeare's most popular plays.

For Michael Davies’s full review, visit whatsonstage.com.

February 18, 2022

RSC, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon

Roy Alexander Weise directs an Afrofuturist production of one of Shakespeare's most popular plays.

For Michael Davies’s full review, visit whatsonstage.com.

The Magician's Elephant conjures up some impressive imagery. Photo by Manuel Harlan.

The Magician's Elephant conjures up some impressive imagery. Photo by Manuel Harlan.

THE MAGICIAN'S ELEPHANT

October 29, 2021

RSC, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon

The RSC conjures up a musical spectacle for a family audience.

For Michael Davies’s full review, visit whatsonstage.com.

October 29, 2021

RSC, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon

The RSC conjures up a musical spectacle for a family audience.

For Michael Davies’s full review, visit whatsonstage.com.

THE COMEDY OF ERRORS

July 20, 2021

RSC, Garden Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Sunday, September 26, 2021, then touring

The Royal Shakespeare Company return to live theatre in a newly-built temporary space on the banks of the River Avon. For Michael Davies's full review visit whatsonstage.com.

July 20, 2021

RSC, Garden Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Sunday, September 26, 2021, then touring

The Royal Shakespeare Company return to live theatre in a newly-built temporary space on the banks of the River Avon. For Michael Davies's full review visit whatsonstage.com.

Jamie Morgan in his mo-cap suit for Dream. Photo by Stuart Martin / RSC

Jamie Morgan in his mo-cap suit for Dream. Photo by Stuart Martin / RSC

DREAM

March 16, 2021

RSC, online until Saturday, March 20, 2021

Billed as a research and development project by the RSC in collaboration with a number of digital and other partners, Dream has only the flimsiest connection with Shakespeare’s nominal source material, A Midsummer Night’s Dream. In fact, it’s a 25-minute exploration of the latest techniques and ambitions of motion-capture, testing how it might work in live performance.

Given that it was originally intended to be staged in a theatre before the pandemic struck, it’s a little unfair to this online version that it can no longer be judged for its potential in a real venue. Instead, the team have created what they jargonistically refer to as “the volume” – a cube of performance space in which actors in motion-capture (or “mo-cap”, to coin more jargon) suits move around, then to be transmogrified by the wonders of the technology into virtual avatars.

These figures move around in a digitally-created world – the forest from A Midsummer Night’s Dream – playing with form and movement to generate a weird visual something-or-other. And if the reviewer’s vocabulary appears to have evaporated, it’s because the technology has outrun traditional forms of critique.

What can certainly be said about it is that it’s not a show in any conventional sense. There’s no narrative as such, merely the chance to watch the digital creations interact with each other in what are clearly remarkably clever ways. For fee-paying ticket-holders, there’s a rather spurious opportunity to join in by using your device to “drop” fireflies into the proceedings at strategic moments.

But if technology isn’t your bag, and you can’t picture the future of theatre as computer-generated graphics instead of real-life actors demonstrating their craft, it all ends up feeling a bit self-indulgent. As R&D it’s interesting enough: theatre it isn’t.

March 16, 2021

RSC, online until Saturday, March 20, 2021

Billed as a research and development project by the RSC in collaboration with a number of digital and other partners, Dream has only the flimsiest connection with Shakespeare’s nominal source material, A Midsummer Night’s Dream. In fact, it’s a 25-minute exploration of the latest techniques and ambitions of motion-capture, testing how it might work in live performance.

Given that it was originally intended to be staged in a theatre before the pandemic struck, it’s a little unfair to this online version that it can no longer be judged for its potential in a real venue. Instead, the team have created what they jargonistically refer to as “the volume” – a cube of performance space in which actors in motion-capture (or “mo-cap”, to coin more jargon) suits move around, then to be transmogrified by the wonders of the technology into virtual avatars.

These figures move around in a digitally-created world – the forest from A Midsummer Night’s Dream – playing with form and movement to generate a weird visual something-or-other. And if the reviewer’s vocabulary appears to have evaporated, it’s because the technology has outrun traditional forms of critique.

What can certainly be said about it is that it’s not a show in any conventional sense. There’s no narrative as such, merely the chance to watch the digital creations interact with each other in what are clearly remarkably clever ways. For fee-paying ticket-holders, there’s a rather spurious opportunity to join in by using your device to “drop” fireflies into the proceedings at strategic moments.

But if technology isn’t your bag, and you can’t picture the future of theatre as computer-generated graphics instead of real-life actors demonstrating their craft, it all ends up feeling a bit self-indulgent. As R&D it’s interesting enough: theatre it isn’t.

Richard Clothier, second left, as reformer Alexander Boyd in The Whip. Photo by Steve Tanner © RSC

Richard Clothier, second left, as reformer Alexander Boyd in The Whip. Photo by Steve Tanner © RSC

THE WHIP

February 11, 2020

RSC, The Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, March 21, 2020

Juliet Gilkes Romero asks some difficult questions in this period piece, ostensibly about the abolition of slavery but plenty of modern resonances.

For Michael Davies’s full review, visit whatsonstage.com

February 11, 2020

RSC, The Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, March 21, 2020

Juliet Gilkes Romero asks some difficult questions in this period piece, ostensibly about the abolition of slavery but plenty of modern resonances.

For Michael Davies’s full review, visit whatsonstage.com

Toby Mocrei and Rufus Hound in The Boy in the Dress. Photo by Manuel Harlan © RSC

Toby Mocrei and Rufus Hound in The Boy in the Dress. Photo by Manuel Harlan © RSC

THE BOY IN THE DRESS

November 27, 2019

RSC, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Sunday March 8, 2020

When David Walliams first turned his hand to writing stories for children in 2008, there were many who hailed him as the natural successor to Roald Dahl. It probably helped that his illustrator was Dahl’s former collaborator Quentin Blake and there was plenty of giggle-inducing snot, farts and general unpleasantness.

It’s easy to see the parallels – and that might be a clue as to what prompted the RSC, in its search for a follow-up to its hit musical Matilda, to settle on this story, the tale of Dennis Sims, whose secret desire to dress up like a girl lands him in hot water at school. What’s interesting is that 11 years ago, the premise might have seemed daring – shocking, even. Today it feels a little old-fashioned, quaint, sweet.

Playwright Mark Ravenhill has done a terrific job with the script, keeping all the naughtiness that children love so much but also filling it with smart one-liners, clever gags and poignancy. If the ending feels a bit of a cheat and less than earned, it’s not for want of trying.

Gregory Doran’s production ticks all the right boxes too. On a fabulously ingenious set designed by Robert Jones, with sharp choreography from Aleta Collins and superb musical direction by Alan Williams – commanding a storming 11-piece band – the show looks and sounds magnificent. Voices are crystal clear, like the storytelling, and production values are everything you could wish for, from some balletic football sequences to a sparkling first-act disco scene.

The performances too are wonderful, led on press night by Toby Mocrei in the title role. His acting and singing are full of authentic emotion, and he has the charisma to carry a show that asks a lot of its young cast. Rufus Hound is beautifully touching as his would-be hardman dad, while the ever-reliable Forbes Masson delivers a terrifying turn as the Scottish headmaster Mr Hawtrey, channelling the teacher in Pink Floyd’s The Wall – even down to shouting his abuse through a megaphone.

The question everyone will really be asking is this: with songs by pop superstar Robbie Williams and his regular co-writer Guy Chambers, does the music stand up? Well, the short answer is yes… to a point. The pair certainly have a wicked way with a memorable tune, as Robbie’s chart career can attest, and there’s more than one catchy refrain repeated along the way here. Whether they constitute musical theatre is probably up for debate: for my money, the outpouring of feelings is too often too on-the-nose, while rhyming and scansion appear to have been cheerfully dispensed with, to have the giants of the genre looking anxiously over their shoulders.

But there’s no debating the response of the audience at this Stratford press night, 24 hours ahead of a gala opening that was expected to attract some major names. Most of the auditorium was on its feet in delight. If a show prompts this kind of eager acceptance that being different is OK, then that’s got to be a good thing, surely.

November 27, 2019

RSC, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Sunday March 8, 2020

When David Walliams first turned his hand to writing stories for children in 2008, there were many who hailed him as the natural successor to Roald Dahl. It probably helped that his illustrator was Dahl’s former collaborator Quentin Blake and there was plenty of giggle-inducing snot, farts and general unpleasantness.

It’s easy to see the parallels – and that might be a clue as to what prompted the RSC, in its search for a follow-up to its hit musical Matilda, to settle on this story, the tale of Dennis Sims, whose secret desire to dress up like a girl lands him in hot water at school. What’s interesting is that 11 years ago, the premise might have seemed daring – shocking, even. Today it feels a little old-fashioned, quaint, sweet.

Playwright Mark Ravenhill has done a terrific job with the script, keeping all the naughtiness that children love so much but also filling it with smart one-liners, clever gags and poignancy. If the ending feels a bit of a cheat and less than earned, it’s not for want of trying.

Gregory Doran’s production ticks all the right boxes too. On a fabulously ingenious set designed by Robert Jones, with sharp choreography from Aleta Collins and superb musical direction by Alan Williams – commanding a storming 11-piece band – the show looks and sounds magnificent. Voices are crystal clear, like the storytelling, and production values are everything you could wish for, from some balletic football sequences to a sparkling first-act disco scene.

The performances too are wonderful, led on press night by Toby Mocrei in the title role. His acting and singing are full of authentic emotion, and he has the charisma to carry a show that asks a lot of its young cast. Rufus Hound is beautifully touching as his would-be hardman dad, while the ever-reliable Forbes Masson delivers a terrifying turn as the Scottish headmaster Mr Hawtrey, channelling the teacher in Pink Floyd’s The Wall – even down to shouting his abuse through a megaphone.

The question everyone will really be asking is this: with songs by pop superstar Robbie Williams and his regular co-writer Guy Chambers, does the music stand up? Well, the short answer is yes… to a point. The pair certainly have a wicked way with a memorable tune, as Robbie’s chart career can attest, and there’s more than one catchy refrain repeated along the way here. Whether they constitute musical theatre is probably up for debate: for my money, the outpouring of feelings is too often too on-the-nose, while rhyming and scansion appear to have been cheerfully dispensed with, to have the giants of the genre looking anxiously over their shoulders.

But there’s no debating the response of the audience at this Stratford press night, 24 hours ahead of a gala opening that was expected to attract some major names. Most of the auditorium was on its feet in delight. If a show prompts this kind of eager acceptance that being different is OK, then that’s got to be a good thing, surely.

Thoroughly modern monarch: Rosie Sheehy as King John. Photo by Steve Tanner © RSC.

Thoroughly modern monarch: Rosie Sheehy as King John. Photo by Steve Tanner © RSC.

KING JOHN

* * * *

September 26, 2019

RSC, The Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday March 21, 2020

RSC debutant director Eleanor Rhode gives Shakespeare’s lesser-performed royal play a vibrant makeover for Brexit Britain.

Read Michael Davies’s full review at whatsonstage.com

* * * *

September 26, 2019

RSC, The Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday March 21, 2020

RSC debutant director Eleanor Rhode gives Shakespeare’s lesser-performed royal play a vibrant makeover for Brexit Britain.

Read Michael Davies’s full review at whatsonstage.com

Kidnapped: The cast surround our critic Michael Davies (second left) in a superfluous attempt to influence his review.

Kidnapped: The cast surround our critic Michael Davies (second left) in a superfluous attempt to influence his review.

TREASURE ISLAND

August 16, 2019

Tread the Boards Productions, The Attic Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Monday, September 21 2019

Never mind 15 men on a dead man’s chest, Tread the Boards’ latest micro-triumph is a swashbuckling romp through Robert Louis Stevenson’s timeless classic delivered by just seven men and women. And a parrot. And a couple of muppets.

And that should tell you all you need to know about this daft but delightful adaptation of the pirate yarn. It’s manic, it’s madcap and it’s moulded to provide a couple of entertaining hours that are very silly indeed. If it wasn’t for that catchy title Stevenson gave it nearly 150 years ago, then Carry On Captain would probably serve just as well.

For this irreverent take on the mutineers’ masterpiece is rooted in a world of very British humour, with glimpses of Basil Fawlty, Blackadder and even ’Allo ’Allo peeking through the yarn that’s being spun. That’s not to say that the adaptation isn’t true to Stevenson’s original – the spine of the story, with its cast of murky characters, sticks closely to the novel. But director John-Robert Partridge never lets duty to the author get in the way of a good gag. Or a bad one, come to that.

In fact, if truth be told, the script is crammed full of jokes that are about as lame as the peg-leg pirate Long John Silver (played with over-the-top relish by Partridge himself). And therein lies much of its charm. The multi-tasking actors love every moment of their costume-changing, identity-swapping anarchy, and the fun is infectious.

From Inspector Clouseau to The Liver Birds, no turn is left unstoned. There’s a brilliantly executed musical interlude in which Matilda Bott and Josh Radcliffe playing a crazed medley of chart hits on duelling ukuleles. There’s a seafaring journey through the Bermuda Triangle featuring every kind of triangle you could imagine, from isosceles to musical. And there are references to every cultural pirate in the book: Jack Sparrow happily rubs shoulders with Captain Pugwash. And there aren’t many places you could write that sentence.

Throw in some wandering eye-patches, special ‘ocean’ effects and some panto-style routines with mops and water-pistols, and it’s about as close as you can get to guaranteeing… well, theatrical treasure. Don’t let on, but the Attic marks the spot.

August 16, 2019

Tread the Boards Productions, The Attic Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Monday, September 21 2019

Never mind 15 men on a dead man’s chest, Tread the Boards’ latest micro-triumph is a swashbuckling romp through Robert Louis Stevenson’s timeless classic delivered by just seven men and women. And a parrot. And a couple of muppets.

And that should tell you all you need to know about this daft but delightful adaptation of the pirate yarn. It’s manic, it’s madcap and it’s moulded to provide a couple of entertaining hours that are very silly indeed. If it wasn’t for that catchy title Stevenson gave it nearly 150 years ago, then Carry On Captain would probably serve just as well.

For this irreverent take on the mutineers’ masterpiece is rooted in a world of very British humour, with glimpses of Basil Fawlty, Blackadder and even ’Allo ’Allo peeking through the yarn that’s being spun. That’s not to say that the adaptation isn’t true to Stevenson’s original – the spine of the story, with its cast of murky characters, sticks closely to the novel. But director John-Robert Partridge never lets duty to the author get in the way of a good gag. Or a bad one, come to that.

In fact, if truth be told, the script is crammed full of jokes that are about as lame as the peg-leg pirate Long John Silver (played with over-the-top relish by Partridge himself). And therein lies much of its charm. The multi-tasking actors love every moment of their costume-changing, identity-swapping anarchy, and the fun is infectious.

From Inspector Clouseau to The Liver Birds, no turn is left unstoned. There’s a brilliantly executed musical interlude in which Matilda Bott and Josh Radcliffe playing a crazed medley of chart hits on duelling ukuleles. There’s a seafaring journey through the Bermuda Triangle featuring every kind of triangle you could imagine, from isosceles to musical. And there are references to every cultural pirate in the book: Jack Sparrow happily rubs shoulders with Captain Pugwash. And there aren’t many places you could write that sentence.

Throw in some wandering eye-patches, special ‘ocean’ effects and some panto-style routines with mops and water-pistols, and it’s about as close as you can get to guaranteeing… well, theatrical treasure. Don’t let on, but the Attic marks the spot.

Lucy Phelps and Sandy Grierson star in Measure for Measure. Photo by Helen Maybanks © RSC.

Lucy Phelps and Sandy Grierson star in Measure for Measure. Photo by Helen Maybanks © RSC.

MEASURE FOR MEASURE

* * * *

July 4, 2019

RSC, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Thursday, August 29, 2019

Artistic director Gregory Doran directs the last of the summer’s three Shakespeare plays at the RSC.

For Michael Davies’s full review, visit whatsonstage.com

* * * *

July 4, 2019

RSC, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Thursday, August 29, 2019

Artistic director Gregory Doran directs the last of the summer’s three Shakespeare plays at the RSC.

For Michael Davies’s full review, visit whatsonstage.com

Jeany Spark intrigues in Crooked Dances at The Other Place. Photo by Ellie Kurttz © RSC.

Jeany Spark intrigues in Crooked Dances at The Other Place. Photo by Ellie Kurttz © RSC.

CROOKED DANCES

* * *

June 26, 2019

RSC, The Other Place, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, July 13, 2019

A new play by Robin French intrigues with its bewildering jumble of ideas and themes.

For Michael Davies’s full review, visit whatsonstage.com

* * *

June 26, 2019

RSC, The Other Place, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, July 13, 2019

A new play by Robin French intrigues with its bewildering jumble of ideas and themes.

For Michael Davies’s full review, visit whatsonstage.com

Jodie McNee in Venice Preserved. Photo by Helen Maybanks © RSC.

Jodie McNee in Venice Preserved. Photo by Helen Maybanks © RSC.

VENICE PRESERVED

* * * *

May 30, 2019

RSC, The Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday September 7, 2019

Michael Davies finds Thomas Otway’s ‘dangerously enticing’ Restoration thriller, directed by Prasanna Puwanarajah, moody and captivating in equal measure.

For the full review, visit whatsonstage.com

* * * *

May 30, 2019

RSC, The Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday September 7, 2019

Michael Davies finds Thomas Otway’s ‘dangerously enticing’ Restoration thriller, directed by Prasanna Puwanarajah, moody and captivating in equal measure.

For the full review, visit whatsonstage.com

Martin Bourne and Katherine Parker-Jones in Aspect Theatre's Duet for One. Photo by David Jones.

Martin Bourne and Katherine Parker-Jones in Aspect Theatre's Duet for One. Photo by David Jones.

DUET FOR ONE

May 16, 2019

Aspect Theatre, The Attic Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, May 18, 2019

This fascinating two-hander was written in 1980 by playwright Tom Kempinski as a vehicle for his then wife, Frances de la Tour. It was subsequently made into a film starring Julie Andrews, and enjoyed a 2009 West End revival with Juliet Stevenson and Henry Goodman.

It reveals, appointment by appointment, the nerve-shredding state of mind of concert violinist Stephanie Abrahams as she offloads to her psychiatrist Dr Feldmann about her struggles with incipient multiple sclerosis. The disease has forced her to give up her career and, over the course of six sessions with the shrink, she approaches her situation with everything from chipper breeziness to outright fury.

Although denied by the playwright, the narrative bears striking similarities to the real-life story of cellist Jacqueline du Pré, and director Marc W Dugmore’s production uses Mendelssohn intelligently to frame and partition the scenes, setting us firmly in a world of classical music. Indeed, the central question posed by the script – is it possible to survive without culture? – is reinforced at every turn.

The tautness of the piece fits well in Stratford’s Attic space. Katherine Parker-Jones as Stephanie and Martin Bourne as the psychiatrist played the roles a couple of years ago at the Swan studio in Worcester and are revisiting the play as the first production by a new company, Aspect Theatre. Aspect will be back at the Attic in November with Patrick Marber’s take on Strindberg, After Miss Julie.

As the debut show from a new company, Duet for One sets a high benchmark. Bourne makes an almost cruelly enigmatic Feldmann, refusing to answer questions or responding with just a raised eyebrow in his cat-and-mouse attempt to get Stephanie to talk. For her part, Parker-Jones carries the burden of the emotional heft of the piece – not to mention a mountainous number of lines – and captures perfectly the broken spirit of an artist denied the ability to create.

They work strongly together, playing off each other with a deftness that is often strikingly effective. The pacing lags from time to time, and the moments of discovery, confession and rage occasionally lack the spark of real electricity, but it’s a sound, sympathetic rendering of a powerful play that deserves a much bigger audience than turned out on this Thursday night in Stratford.

May 16, 2019

Aspect Theatre, The Attic Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, May 18, 2019

This fascinating two-hander was written in 1980 by playwright Tom Kempinski as a vehicle for his then wife, Frances de la Tour. It was subsequently made into a film starring Julie Andrews, and enjoyed a 2009 West End revival with Juliet Stevenson and Henry Goodman.

It reveals, appointment by appointment, the nerve-shredding state of mind of concert violinist Stephanie Abrahams as she offloads to her psychiatrist Dr Feldmann about her struggles with incipient multiple sclerosis. The disease has forced her to give up her career and, over the course of six sessions with the shrink, she approaches her situation with everything from chipper breeziness to outright fury.

Although denied by the playwright, the narrative bears striking similarities to the real-life story of cellist Jacqueline du Pré, and director Marc W Dugmore’s production uses Mendelssohn intelligently to frame and partition the scenes, setting us firmly in a world of classical music. Indeed, the central question posed by the script – is it possible to survive without culture? – is reinforced at every turn.

The tautness of the piece fits well in Stratford’s Attic space. Katherine Parker-Jones as Stephanie and Martin Bourne as the psychiatrist played the roles a couple of years ago at the Swan studio in Worcester and are revisiting the play as the first production by a new company, Aspect Theatre. Aspect will be back at the Attic in November with Patrick Marber’s take on Strindberg, After Miss Julie.

As the debut show from a new company, Duet for One sets a high benchmark. Bourne makes an almost cruelly enigmatic Feldmann, refusing to answer questions or responding with just a raised eyebrow in his cat-and-mouse attempt to get Stephanie to talk. For her part, Parker-Jones carries the burden of the emotional heft of the piece – not to mention a mountainous number of lines – and captures perfectly the broken spirit of an artist denied the ability to create.

They work strongly together, playing off each other with a deftness that is often strikingly effective. The pacing lags from time to time, and the moments of discovery, confession and rage occasionally lack the spark of real electricity, but it’s a sound, sympathetic rendering of a powerful play that deserves a much bigger audience than turned out on this Thursday night in Stratford.

THE PROVOKED WIFE

* * *

May 9, 2019

RSC, The Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday September 7, 2019

John Vanbrugh’s broad, rather seedy 1697 comedy is given an unironic staging with Phillip Breen directing Caroline Quentin, Jonathan Slinger, Alexandra Gilbreath and Rufus Hound.

For Michael Davies’s full review, visit whatsonstage.com

Right: Rufus Hound as Constant in The Provoked Wife. Photo by Pete Le May © RSC.

* * *

May 9, 2019

RSC, The Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday September 7, 2019

John Vanbrugh’s broad, rather seedy 1697 comedy is given an unironic staging with Phillip Breen directing Caroline Quentin, Jonathan Slinger, Alexandra Gilbreath and Rufus Hound.

For Michael Davies’s full review, visit whatsonstage.com

Right: Rufus Hound as Constant in The Provoked Wife. Photo by Pete Le May © RSC.

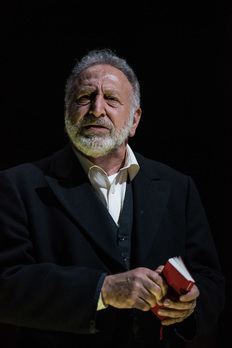

Poignant: Philip Leach in the title role of Tread the Boards' production of King Lear.

Poignant: Philip Leach in the title role of Tread the Boards' production of King Lear.

KING LEAR

April 14, 2019

Tread the Boards Productions, The Attic Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Sunday, April 21, 2019

You could hardly accuse Stratford’s fringe company Tread the Boards of not being ambitious. Not exactly graced with the resources of their internationally famous Shakespearean colleagues across Bancroft Gardens, this enterprising outfit celebrates its tenth year in the home of the Bard with two contrasting productions. Much Ado (reviewed below) provides the laughs: King Lear offers gravitas by the bucketload.

Anyone familiar with the company will not be surprised to learn that the sizeable ensemble has strength in depth, with even the smallest roles delivered with real talent and a youthful energy. Tread the Boards manage to source skilful actors in sufficient numbers to make a production of this scale really work in the tiny loft space of the Attic Theatre.

The wide and shallow playing space means the action is never more than a few inches away from the studio theatre audience, and director John-Robert Partridge exploits the opportunities for intimacy and immediacy that the intense proximity supplies. Effective lighting by Kat Murray and a simple set design by Zoe Rolph also contribute to the overall impact.

Among the players, Matilda Bott doubles intriguingly as Cordelia and the Fool, demonstrating both innocence as the former and a talent for tomfoolery as the latter, while Pete Meredith’s villainous Edmund is charismatic and sinister in equal measure. But the truth is that the acting is universally top-notch, and one of the greatest feathers in the cap of this small but beautifully formed troupe.

Appropriately enough, assuming the performing crown is Philip Leach in the title role. Generally accepted as the Everest of Shakespearean parts, Lear ranges from rage to insanity, poignancy to pathos, and Leach can do them all. There’s never a moment when he’s on stage when you find yourself analysing the acting: it’s always believable, truthful and emotionally engaging. The wayward monarch’s descent from megalomania to madness is intelligently drawn, and Shakespeare’s language is delivered with consistency and care.

At a little over three hours, the production could probably stand a tad more editing, but there’s no denying the quality of the company and its commitment to offering a visceral, vibrant alternative to the big boys (and girls) up the road. There’s nothing second-class about these citizens.

King Lear plays in repertory with Much Ado About Nothing until Sunday, April 21, 2019.

April 14, 2019

Tread the Boards Productions, The Attic Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Sunday, April 21, 2019

You could hardly accuse Stratford’s fringe company Tread the Boards of not being ambitious. Not exactly graced with the resources of their internationally famous Shakespearean colleagues across Bancroft Gardens, this enterprising outfit celebrates its tenth year in the home of the Bard with two contrasting productions. Much Ado (reviewed below) provides the laughs: King Lear offers gravitas by the bucketload.

Anyone familiar with the company will not be surprised to learn that the sizeable ensemble has strength in depth, with even the smallest roles delivered with real talent and a youthful energy. Tread the Boards manage to source skilful actors in sufficient numbers to make a production of this scale really work in the tiny loft space of the Attic Theatre.

The wide and shallow playing space means the action is never more than a few inches away from the studio theatre audience, and director John-Robert Partridge exploits the opportunities for intimacy and immediacy that the intense proximity supplies. Effective lighting by Kat Murray and a simple set design by Zoe Rolph also contribute to the overall impact.

Among the players, Matilda Bott doubles intriguingly as Cordelia and the Fool, demonstrating both innocence as the former and a talent for tomfoolery as the latter, while Pete Meredith’s villainous Edmund is charismatic and sinister in equal measure. But the truth is that the acting is universally top-notch, and one of the greatest feathers in the cap of this small but beautifully formed troupe.

Appropriately enough, assuming the performing crown is Philip Leach in the title role. Generally accepted as the Everest of Shakespearean parts, Lear ranges from rage to insanity, poignancy to pathos, and Leach can do them all. There’s never a moment when he’s on stage when you find yourself analysing the acting: it’s always believable, truthful and emotionally engaging. The wayward monarch’s descent from megalomania to madness is intelligently drawn, and Shakespeare’s language is delivered with consistency and care.

At a little over three hours, the production could probably stand a tad more editing, but there’s no denying the quality of the company and its commitment to offering a visceral, vibrant alternative to the big boys (and girls) up the road. There’s nothing second-class about these citizens.

King Lear plays in repertory with Much Ado About Nothing until Sunday, April 21, 2019.

Brisk and breezy: John Robert Partridge and Alexandra Whitworth as Beatrice and Benedick.

Brisk and breezy: John Robert Partridge and Alexandra Whitworth as Beatrice and Benedick.

MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING

April 6, 2019

Tread the Boards Productions, The Attic Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Sunday, April 28, 2019

Those in the know understand that there is more to Stratford-upon-Avon’s Shakespearean offerings than the RSC. Just across Bancroft Gardens, snuggled in the beams of the Cox’s Yard complex, sits The Attic, whose resident company Tread the Boards regularly delivers some of the most consistently enjoyable and audience-friendly productions of the Bard that you could wish for.

Much Ado, directed by first-timers Matilda Bott and Robert Moore, follows in a long line of appealing, accessible productions of Will’s works, and brings the company’s usual spirit of playfulness and professionalism to bear on the tale of sparring partners Beatrice and Benedick.

Performed in modern dress, on a stage adorned with a lush green lawn and strung with fairy lights, this brisk, breezy interpretation wisely concentrates on the will-they-won’t-they pairing at its heart, while side plots involving the scheming uncle Don John and the dim-witted yokels who make up the neighbourhood watch are given just enough room to make sense without becoming a wearisome distraction.

John Robert Partridge as Benedick has a wonderful facility with the language, ranging intelligently from high comedy to charming pathos, and he’s ably supported by Georgia Kelly and Pete Meredith as his compatriots Donna Patricia and Claudio respectively. Alexandra Whitworth’s Beatrice has flashes of sparkle, and her interactions with her cousin Hero (Kate Gee Finch) are full of fun, while the directors contribute nice cameos as Don John (Moore) and Dogberry – a show-stealing turn in twinset and pearls by Bott.

The action is beautifully paced and the simplicity of the set and lighting (Kat Murray) helps keep the focus on the well-spoken text. The intimacy of the space means there’s precious little room for manoeuvre and every performing nuance is exposed, but with hands as safe as these, that’s never an issue.

Much Ado About Nothing plays in repertory with King Lear until Sunday, April 28, 2019.

April 6, 2019

Tread the Boards Productions, The Attic Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Sunday, April 28, 2019

Those in the know understand that there is more to Stratford-upon-Avon’s Shakespearean offerings than the RSC. Just across Bancroft Gardens, snuggled in the beams of the Cox’s Yard complex, sits The Attic, whose resident company Tread the Boards regularly delivers some of the most consistently enjoyable and audience-friendly productions of the Bard that you could wish for.

Much Ado, directed by first-timers Matilda Bott and Robert Moore, follows in a long line of appealing, accessible productions of Will’s works, and brings the company’s usual spirit of playfulness and professionalism to bear on the tale of sparring partners Beatrice and Benedick.

Performed in modern dress, on a stage adorned with a lush green lawn and strung with fairy lights, this brisk, breezy interpretation wisely concentrates on the will-they-won’t-they pairing at its heart, while side plots involving the scheming uncle Don John and the dim-witted yokels who make up the neighbourhood watch are given just enough room to make sense without becoming a wearisome distraction.

John Robert Partridge as Benedick has a wonderful facility with the language, ranging intelligently from high comedy to charming pathos, and he’s ably supported by Georgia Kelly and Pete Meredith as his compatriots Donna Patricia and Claudio respectively. Alexandra Whitworth’s Beatrice has flashes of sparkle, and her interactions with her cousin Hero (Kate Gee Finch) are full of fun, while the directors contribute nice cameos as Don John (Moore) and Dogberry – a show-stealing turn in twinset and pearls by Bott.

The action is beautifully paced and the simplicity of the set and lighting (Kat Murray) helps keep the focus on the well-spoken text. The intimacy of the space means there’s precious little room for manoeuvre and every performing nuance is exposed, but with hands as safe as these, that’s never an issue.

Much Ado About Nothing plays in repertory with King Lear until Sunday, April 28, 2019.

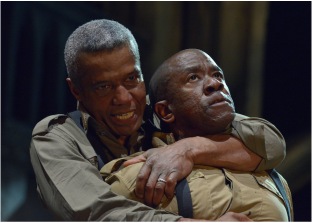

Black and white: John Kani and Antony Sher star in Kani's new play Kunene and the King. Photo by Ellie Kurttz © RSC.

Black and white: John Kani and Antony Sher star in Kani's new play Kunene and the King. Photo by Ellie Kurttz © RSC.

KUNENE AND THE KING

* * * *

April 3, 2019

RSC, Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Tuesday, April 23, 2019

John Kani’s deeply personal new play about the impact of apartheid 25 years on stars the playwright and RSC stalwart Antony Sher.

For Michael Davies’s full review, visit whatsonstage.com

* * * *

April 3, 2019

RSC, Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Tuesday, April 23, 2019

John Kani’s deeply personal new play about the impact of apartheid 25 years on stars the playwright and RSC stalwart Antony Sher.

For Michael Davies’s full review, visit whatsonstage.com

Tricky: Claire Price stars as Petruchia in the gender-swapped production of The Taming of the Shrew. Photo by Ikin Yum © RSC.

Tricky: Claire Price stars as Petruchia in the gender-swapped production of The Taming of the Shrew. Photo by Ikin Yum © RSC.

THE TAMING OF THE SHREW

* * * *

March 19, 2019

RSC, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday August 31, 2019, then touring

A gender-swapped version of Shakespeare’s tricky play, directed by Justin Audibert, plays in rep with As You Like It and Measure for Measure.

For Michael Davies’s full review, visit whatsonstage.com

* * * *

March 19, 2019

RSC, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday August 31, 2019, then touring

A gender-swapped version of Shakespeare’s tricky play, directed by Justin Audibert, plays in rep with As You Like It and Measure for Measure.

For Michael Davies’s full review, visit whatsonstage.com

Sophie Khan Levy and Lucy Phelps as Celia and Rosalind. Photo by Topher McGrillis. © RSC.

Sophie Khan Levy and Lucy Phelps as Celia and Rosalind. Photo by Topher McGrillis. © RSC.

AS YOU LIKE IT

* * *

February 21, 2019

RSC, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday August 31, 2019, then touring

Kimberley Sykes directs the first in the RSC’s new ensemble season.

For Michael Davies’s full review, visit whatsonstage.com

* * *

February 21, 2019

RSC, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday August 31, 2019, then touring

Kimberley Sykes directs the first in the RSC’s new ensemble season.

For Michael Davies’s full review, visit whatsonstage.com

Kathryn Hunter stars as Timon of Athens. Photo by Simon Annand © RSC.

Kathryn Hunter stars as Timon of Athens. Photo by Simon Annand © RSC.

TIMON OF ATHENS

* * * *

December 12, 2018

RSC, Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Friday, February 22, 2019

Kathryn Hunter stars in Simon Godwin’s filleted version of Shakespeare’s play.

For Michael Davies’s full review, visit whatsonstage.com

* * * *

December 12, 2018

RSC, Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Friday, February 22, 2019

Kathryn Hunter stars in Simon Godwin’s filleted version of Shakespeare’s play.

For Michael Davies’s full review, visit whatsonstage.com

Trying It On: David Edgar, writer and performer.

Trying It On: David Edgar, writer and performer.

TRYING IT ON

* * * *

October 19, 2018

RSC, The Other Place, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, October 20, 2018

David Edgar’s 1983 play Maydays reaches the end of its all-too-brief run at Stratford’s The Other Place after shaking up quite a few preconceptions and shining a harsh spotlight on today’s political agenda. Now, to coincide with its closure, the playwright himself gives just three performances of his own one-man show as a kind of companion piece.

Devised following a conversation in which he mused about how he would explain his current political thinking to his younger self – 50 years younger, in fact – Trying It On is a glorious mix of self-effacing fallibility, hilarious pomposity-pricking and biting social comment. Its form (which I won’t divulge for fear of giving too much away) matches the brilliance of its content and it’s no trouble at all to set aside the acting shortcomings of a man who, by his own admission, hasn’t performed on a stage since his student days, and never professionally.

And while he doesn’t let himself off the hook, with frequent challenges to his relative inaction politically or his ‘selling out’ to become a mainstream writer, neither does he allow the audience to be complacent. Instead, we are invited to reflect on our own complicity in creating a world – and legacy – which could hardly be said to be inspiring to the generations coming along behind.

These tough messages are wrapped up in flashes of Edgar humour, but retain their sting nonetheless. Director Christopher Haydon and designer Frankie Bradshaw position their man in front of an array of cardboard boxes and filing cabinets which serve as both backdrop for projected images and video and useful containers for some selectively employed props. The effect is simple but clever, supplementing Edgar’s 90-minute monologue without ever overpowering it.

He’s said to have had second thoughts about going through with the whole project, but it’s a tribute to his resilience, natural charm and profundity that Trying It On carries such a powerful punch. It may not claim a gong for acting, but the production is unquestionably a winner.

* * * *

October 19, 2018

RSC, The Other Place, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, October 20, 2018

David Edgar’s 1983 play Maydays reaches the end of its all-too-brief run at Stratford’s The Other Place after shaking up quite a few preconceptions and shining a harsh spotlight on today’s political agenda. Now, to coincide with its closure, the playwright himself gives just three performances of his own one-man show as a kind of companion piece.

Devised following a conversation in which he mused about how he would explain his current political thinking to his younger self – 50 years younger, in fact – Trying It On is a glorious mix of self-effacing fallibility, hilarious pomposity-pricking and biting social comment. Its form (which I won’t divulge for fear of giving too much away) matches the brilliance of its content and it’s no trouble at all to set aside the acting shortcomings of a man who, by his own admission, hasn’t performed on a stage since his student days, and never professionally.

And while he doesn’t let himself off the hook, with frequent challenges to his relative inaction politically or his ‘selling out’ to become a mainstream writer, neither does he allow the audience to be complacent. Instead, we are invited to reflect on our own complicity in creating a world – and legacy – which could hardly be said to be inspiring to the generations coming along behind.

These tough messages are wrapped up in flashes of Edgar humour, but retain their sting nonetheless. Director Christopher Haydon and designer Frankie Bradshaw position their man in front of an array of cardboard boxes and filing cabinets which serve as both backdrop for projected images and video and useful containers for some selectively employed props. The effect is simple but clever, supplementing Edgar’s 90-minute monologue without ever overpowering it.

He’s said to have had second thoughts about going through with the whole project, but it’s a tribute to his resilience, natural charm and profundity that Trying It On carries such a powerful punch. It may not claim a gong for acting, but the production is unquestionably a winner.

Distress call: Richard Cant as Jeremy in David Edgar's epic Maydays. Photo by Richard Lakos © RSC.

Distress call: Richard Cant as Jeremy in David Edgar's epic Maydays. Photo by Richard Lakos © RSC.

MAYDAYS

* * * *

October 12, 2018

RSC, The Other Place, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, October 20, 2018

It’s been 35 years since David Edgar’s exploration of the roots of Thatcherism was first staged by the RSC. Then, it was at The Barbican in London with a cast of 20 and a contemporary urgency that put a harsh spotlight on the failings of the political left.

Today, it’s got a surprisingly fresh feel to it, and much of that urgency remains. In reworking it for a cast half the size and the studio setting of Stratford’s Other Place, Edgar has transformed it into a history play that still carries significant resonance for a 2018 audience.

It’s political polemic, there are no two ways about it. And while the arguments are constantly shifting in the mouths and minds of the characters, it’s ultimately a hectoring, didactic piece of theatre that never quite breaks free of its politics to engage the heart as strongly as it does the brain.

That’s not to say it isn’t epic, timely and beautifully written, and in the hands of director Owen Horsley and his team it is impeccably delivered, with a carefully judged mix of vinegar and honey. Richard Cant’s pragmatic socialist Jeremy, in particular, smooths the edges of revolutionary zeal with disarming charm and credibility. Mark Quartley as his student Martin is all fire and vibrancy in his youth, but later swayed by middle age and his mentor into a new perspective.

The characters’ through lines are all clearly drawn and the way Edgar has restructured the piece to bring them together in the third part feels less contrived than it might, although his conclusions are far less tidy than his plotting. And quite right too: with the benefit of several decades of hindsight, and with the world in its current state of turmoil, things look much less straightforward than they used to. As Martin angrily demands of his erstwhile communist chums, how will we look back on these days and events in five years’ time?

Horsley and his designer Simon Wells accentuate the themes of each of Edgar’s three unevenly divided sections with the staging. The first part, performed in the round, focuses on the student anger of the post-war years and 1960s, when communal groups worked together to fight the battle of the oppressed. Switching to Cold War Eastern Europe, the theatre is reconfigured as a traverse stage, emphasizing the us-and-them nature of the struggle. By the third part, as Jeremy and Martin both succumb to the practicalities of a kind of libertarian conservatism, the staging has become a conventional end-on theatre – traditional and safe, one might infer.

But the power and strength of all the ensemble’s performances – whether major role or minor supporting player – make this far from safe, and fully in keeping with The Other Place’s stated mission to shake up our view of society. As its title implies, Maydays remains Edgar’s urgent distress call to an increasingly topsy-turvy world.

* * * *

October 12, 2018

RSC, The Other Place, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, October 20, 2018

It’s been 35 years since David Edgar’s exploration of the roots of Thatcherism was first staged by the RSC. Then, it was at The Barbican in London with a cast of 20 and a contemporary urgency that put a harsh spotlight on the failings of the political left.

Today, it’s got a surprisingly fresh feel to it, and much of that urgency remains. In reworking it for a cast half the size and the studio setting of Stratford’s Other Place, Edgar has transformed it into a history play that still carries significant resonance for a 2018 audience.

It’s political polemic, there are no two ways about it. And while the arguments are constantly shifting in the mouths and minds of the characters, it’s ultimately a hectoring, didactic piece of theatre that never quite breaks free of its politics to engage the heart as strongly as it does the brain.

That’s not to say it isn’t epic, timely and beautifully written, and in the hands of director Owen Horsley and his team it is impeccably delivered, with a carefully judged mix of vinegar and honey. Richard Cant’s pragmatic socialist Jeremy, in particular, smooths the edges of revolutionary zeal with disarming charm and credibility. Mark Quartley as his student Martin is all fire and vibrancy in his youth, but later swayed by middle age and his mentor into a new perspective.

The characters’ through lines are all clearly drawn and the way Edgar has restructured the piece to bring them together in the third part feels less contrived than it might, although his conclusions are far less tidy than his plotting. And quite right too: with the benefit of several decades of hindsight, and with the world in its current state of turmoil, things look much less straightforward than they used to. As Martin angrily demands of his erstwhile communist chums, how will we look back on these days and events in five years’ time?

Horsley and his designer Simon Wells accentuate the themes of each of Edgar’s three unevenly divided sections with the staging. The first part, performed in the round, focuses on the student anger of the post-war years and 1960s, when communal groups worked together to fight the battle of the oppressed. Switching to Cold War Eastern Europe, the theatre is reconfigured as a traverse stage, emphasizing the us-and-them nature of the struggle. By the third part, as Jeremy and Martin both succumb to the practicalities of a kind of libertarian conservatism, the staging has become a conventional end-on theatre – traditional and safe, one might infer.

But the power and strength of all the ensemble’s performances – whether major role or minor supporting player – make this far from safe, and fully in keeping with The Other Place’s stated mission to shake up our view of society. As its title implies, Maydays remains Edgar’s urgent distress call to an increasingly topsy-turvy world.

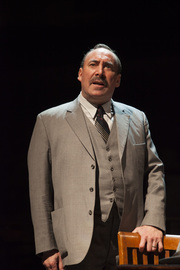

Jude Owusu as Tamburlaine. Photo by Ellie Kurttz © RSC.

Jude Owusu as Tamburlaine. Photo by Ellie Kurttz © RSC.

TAMBURLAINE

* * * *

August 28, 2018

RSC, Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, December 1, 2018

For ten years, Michael Boyd ran the RSC, overseeing the construction of the new main house and the redevelopment of The Other Place. This undoubtedly gave him invaluable insight into how the organisation’s three theatre spaces work, and it’s knowledge that he has put to excellent use in this condensed production of Christopher Marlowe’s bloody history plays.

The Swan is often cited by performers and directors alike as one of their favourite houses in the world, and on this showing it’s easy to see why. Designer Tom Piper has worked brilliantly with director Boyd to locate the many and varied battles and conquests in a semi-recognisable world of greatcoats, AK47s and metallic surfaces. Ladders, grilles and spot-welds abound, creating a kind of gothic dystopia familiar to sci-fi fans yet somehow clearly rooted in Marlowe’s Elizabethan milieu.

This, together with an explosive, percussion-heavy score by James Jones, lays the groundwork for some very fine ensemble performances, strongly reminiscent of the Shakespeare Histories cycle that Boyd directed when he ran the place. Some startling doubling of roles – often achieved with a knowing look to the audience – enables through lines of narratives to emerge even more clearly, so that the double-dealing brother of Persian king Mycetes later becomes the treacherous King of Hungary, both meeting a grisly end at the hands of the eponymous Tamburlaine.

Boyd’s smart decision to fillet Marlowe’s original two plays into one (albeit long) production pays off handsomely, with the storytelling placed firmly centre stage throughout. There may be moments when one bloodthirsty siege starts to look much like another, but the ingenuity of Tamburlaine in finding increasingly sickening and vengeful penalties for his enemies is particularly impressive.

Boyd wisely opts for symbolic representations of the on-stage executions and deaths by having victims smeared with blood from a bucket or, in more extreme cases, having the bucket’s contents emptied over them. On the basis of ‘less is more’, the impact of this symbolism is to enhance its power, even if it requires a small army of stagehands to clear up the mess in the interval.

There are many excellent performances across the company. David Sturzaker speaks the language impeccably and is unquestionably a star Shakespearian in the making; Rosy McEwen appears and sounds serenely controlled as the tyrant’s wife Zenocrate; and Sagar IM Arya and Debbie Korley make a tragic Turkish emperor and empress humiliated beyond endurance.

At the heart of the production is a towering performance from Jude Owusu, who gives Tamburlaine himself enough depth and dimension to range from our sympathy to our outright horror at the vulnerability of the man or the jaw-dropping inhumanity of the despot. He’s every inch the soldier, but also a loving husband reduced to a quivering wreck at the death of his queen. And yet he’s credibly capable of murdering the son who fails to live up to his ideals of what a warmongering ruler should be.

It’s dark, it’s highly resonant for these troubled times and it’s a gruelling three-and-a-quarter hours long, but as a tribute to the vibrant, rollicking narrative style of the young Kit Marlowe, it makes a noise almost as thunderous as the percussion.

* * * *

August 28, 2018

RSC, Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, December 1, 2018

For ten years, Michael Boyd ran the RSC, overseeing the construction of the new main house and the redevelopment of The Other Place. This undoubtedly gave him invaluable insight into how the organisation’s three theatre spaces work, and it’s knowledge that he has put to excellent use in this condensed production of Christopher Marlowe’s bloody history plays.

The Swan is often cited by performers and directors alike as one of their favourite houses in the world, and on this showing it’s easy to see why. Designer Tom Piper has worked brilliantly with director Boyd to locate the many and varied battles and conquests in a semi-recognisable world of greatcoats, AK47s and metallic surfaces. Ladders, grilles and spot-welds abound, creating a kind of gothic dystopia familiar to sci-fi fans yet somehow clearly rooted in Marlowe’s Elizabethan milieu.

This, together with an explosive, percussion-heavy score by James Jones, lays the groundwork for some very fine ensemble performances, strongly reminiscent of the Shakespeare Histories cycle that Boyd directed when he ran the place. Some startling doubling of roles – often achieved with a knowing look to the audience – enables through lines of narratives to emerge even more clearly, so that the double-dealing brother of Persian king Mycetes later becomes the treacherous King of Hungary, both meeting a grisly end at the hands of the eponymous Tamburlaine.

Boyd’s smart decision to fillet Marlowe’s original two plays into one (albeit long) production pays off handsomely, with the storytelling placed firmly centre stage throughout. There may be moments when one bloodthirsty siege starts to look much like another, but the ingenuity of Tamburlaine in finding increasingly sickening and vengeful penalties for his enemies is particularly impressive.

Boyd wisely opts for symbolic representations of the on-stage executions and deaths by having victims smeared with blood from a bucket or, in more extreme cases, having the bucket’s contents emptied over them. On the basis of ‘less is more’, the impact of this symbolism is to enhance its power, even if it requires a small army of stagehands to clear up the mess in the interval.

There are many excellent performances across the company. David Sturzaker speaks the language impeccably and is unquestionably a star Shakespearian in the making; Rosy McEwen appears and sounds serenely controlled as the tyrant’s wife Zenocrate; and Sagar IM Arya and Debbie Korley make a tragic Turkish emperor and empress humiliated beyond endurance.

At the heart of the production is a towering performance from Jude Owusu, who gives Tamburlaine himself enough depth and dimension to range from our sympathy to our outright horror at the vulnerability of the man or the jaw-dropping inhumanity of the despot. He’s every inch the soldier, but also a loving husband reduced to a quivering wreck at the death of his queen. And yet he’s credibly capable of murdering the son who fails to live up to his ideals of what a warmongering ruler should be.

It’s dark, it’s highly resonant for these troubled times and it’s a gruelling three-and-a-quarter hours long, but as a tribute to the vibrant, rollicking narrative style of the young Kit Marlowe, it makes a noise almost as thunderous as the percussion.

Very merry: David Troughton and Beth Cordingly. Photo by Manuel Harlan © RSC.

Very merry: David Troughton and Beth Cordingly. Photo by Manuel Harlan © RSC.

THE MERRY WIVES OF WINDSOR

* * *

August 14, 2018

RSC, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday September 22, 2018

Fiona Laird’s modern-dress version transposes Windsor to Essex, with David Troughton starring as the fat knight Falstaff.

For Michael Davies’s full review, visit whatsonstage.com

* * *

August 14, 2018

RSC, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday September 22, 2018

Fiona Laird’s modern-dress version transposes Windsor to Essex, with David Troughton starring as the fat knight Falstaff.

For Michael Davies’s full review, visit whatsonstage.com

THE WIZARD OF OZ

August 10, 2018

Tread the Boards Theatre Company, The Attic Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Monday, August 27, 2018

There can hardly be an adult alive today who does not know The Wizard of Oz inside out: thanks to perennial Christmas repetitions of the 1939 Judy Garland film, it’s pretty much in everybody’s DNA. Featuring the first major use of Technicolor, it is, of course, a colossal extravaganza of song, dance, special effects and big-budget spectacle.

Which might make you worry about the capabilities of a tiny production, performed by a cast of just seven in an intimate black-box studio theatre above a pub in Stratford-upon-Avon.

But if you think small scale means small ambition, then think again. Tread the Boards Theatre Company – fast approaching its tenth anniversary in the cosy Attic Theatre – manages to make this energetic, joyful production into something that is every bit as spectacular as its glossy predecessor.

Some of it they achieve by borrowing freely from the movie, including Dorothy’s signature song Over the Rainbow, large chunks of instantly recognisable dialogue and the gleeful cackle of the Wicked Witch of the West. But the rest is pure Tread the Boards, an effervescent mixture of idiosyncratic humour, knockabout silliness and, above all, crystal-clear storytelling.

This adaptation veers away from its film forebear in numerous narrative ways, including a number of wonderfully over-the-top character roles by Daniel Arbon, who spends half the time channelling Monty Python and the other half Robin Williams. In fact, he’d be in danger of stealing the show from Dorothy and her three travelling companions were it not for the fact that they are uniformly superb.