Natascha McElhone (left) as Sarah Churchill and Emma Cunniffe as Queen Anne. Photo by Manuel Harlan (c) RSC.

Natascha McElhone (left) as Sarah Churchill and Emma Cunniffe as Queen Anne. Photo by Manuel Harlan (c) RSC.

QUEEN ANNE

* * * *

December 4, 2015

RSC, The Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, January 23, 2016

CONSIDERING the political machinations and personal intrigues surrounding this largely forgotten British monarch, it’s somewhat surprising that no-one has thought to make a play about her before now. Helen Edmundson rectifies that with an intelligent, if wordy, play that premieres in the fitting environs of the RSC’s Swan Theatre.

Running at almost three hours, it’s a hefty, complex construction that demands much of its audience, but delivers considerable returns for that attention. Director Natalie Abrahami keeps the production straightforward and sparse, aiding the comprehension by not overloading it with superfluous dressings and business. The emphasis is very much on the performances.

The narrative traces the crisis around the succession to the throne as Protestant Anne moves out of her child-bearing years, having endured 17 pregnancies without any full-grown offspring to show for them. The possibility of a Hanoverian successor or – worse – a Catholic one exercises the advisers and politicians around her almost as much as it troubles the queen herself.

Meanwhile, in her difficult personal life, Anne is struggling to maintain her childhood friendship with Sarah Churchill, wife of the dashing military leader who will become Lord Marlborough and win a thrilling victory at Blenheim. The pressure of the politicians and the people, as represented by satirists Jonathan Swift and Daniel Defoe, takes a heavy toll on the relationship.

For all the wheeling and dealing of the different factions, it’s this personal drama that carries greatest potential for emotional exploration, and it feels like a missed opportunity when Edmundson opts for the political story as her main thread. Having said that, she makes the dense subject matter work excitingly, always rendering the twists and turns with clarity and authenticity.

In the title role, Emma Cunniffe grows throughout the evening, starting as a naïve pawn and emerging as a political heavyweight in her own right. From the frail fragility of her latest failed pregnancy, she develops a steely self-determination that provides a real engine for the story.

Opposite her, making her RSC debut, Natascha McElhone goes the other way, crashing from a striking schemer to a spent force in spectacular fashion. Her final speech, claiming to be the greatest woman of her age, has a brilliant hollowness to it, reinforced by the lurking figure of Anne, seeming to claim that mantle for herself instead.

Across the capable cast, there are many delightful cameos, from Michael Fenton Stevens’s quack of a doctor to Jonathan Broadbent’s sycophantic Leader of the Commons. Hannah Clark’s simple set serves to highlight the significance of the words and there are some credibly entertaining satirical songs by Edmundson that help leaven the atmosphere at strategic points.

Quite apart from anything else, it’s wonderful to see a new play with such meaty roles for two leading women, piggybacking on the Swan’s 2014 Roaring Girls season to keep strong female characters firmly in the spotlight.

* * * *

December 4, 2015

RSC, The Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, January 23, 2016

CONSIDERING the political machinations and personal intrigues surrounding this largely forgotten British monarch, it’s somewhat surprising that no-one has thought to make a play about her before now. Helen Edmundson rectifies that with an intelligent, if wordy, play that premieres in the fitting environs of the RSC’s Swan Theatre.

Running at almost three hours, it’s a hefty, complex construction that demands much of its audience, but delivers considerable returns for that attention. Director Natalie Abrahami keeps the production straightforward and sparse, aiding the comprehension by not overloading it with superfluous dressings and business. The emphasis is very much on the performances.

The narrative traces the crisis around the succession to the throne as Protestant Anne moves out of her child-bearing years, having endured 17 pregnancies without any full-grown offspring to show for them. The possibility of a Hanoverian successor or – worse – a Catholic one exercises the advisers and politicians around her almost as much as it troubles the queen herself.

Meanwhile, in her difficult personal life, Anne is struggling to maintain her childhood friendship with Sarah Churchill, wife of the dashing military leader who will become Lord Marlborough and win a thrilling victory at Blenheim. The pressure of the politicians and the people, as represented by satirists Jonathan Swift and Daniel Defoe, takes a heavy toll on the relationship.

For all the wheeling and dealing of the different factions, it’s this personal drama that carries greatest potential for emotional exploration, and it feels like a missed opportunity when Edmundson opts for the political story as her main thread. Having said that, she makes the dense subject matter work excitingly, always rendering the twists and turns with clarity and authenticity.

In the title role, Emma Cunniffe grows throughout the evening, starting as a naïve pawn and emerging as a political heavyweight in her own right. From the frail fragility of her latest failed pregnancy, she develops a steely self-determination that provides a real engine for the story.

Opposite her, making her RSC debut, Natascha McElhone goes the other way, crashing from a striking schemer to a spent force in spectacular fashion. Her final speech, claiming to be the greatest woman of her age, has a brilliant hollowness to it, reinforced by the lurking figure of Anne, seeming to claim that mantle for herself instead.

Across the capable cast, there are many delightful cameos, from Michael Fenton Stevens’s quack of a doctor to Jonathan Broadbent’s sycophantic Leader of the Commons. Hannah Clark’s simple set serves to highlight the significance of the words and there are some credibly entertaining satirical songs by Edmundson that help leaven the atmosphere at strategic points.

Quite apart from anything else, it’s wonderful to see a new play with such meaty roles for two leading women, piggybacking on the Swan’s 2014 Roaring Girls season to keep strong female characters firmly in the spotlight.

Mariah Gale and Rhys Rusbatch fly as Wendy and Peter Pan. Photo by Manuel Harlan. (c) RSC

Mariah Gale and Rhys Rusbatch fly as Wendy and Peter Pan. Photo by Manuel Harlan. (c) RSC

WENDY AND PETER PAN

* * * *

November 25, 2015

RSC, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Sunday, January 31, 2016

Ella Hickson’s retelling of the JM Barrie classic returns for a second boisterous helping.

For the full review visit whatsonstage.com

* * * *

November 25, 2015

RSC, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Sunday, January 31, 2016

Ella Hickson’s retelling of the JM Barrie classic returns for a second boisterous helping.

For the full review visit whatsonstage.com

Restoration romp: Tom Turner (left) and Jonathan Broadbent in Love for Love. Photo by Ellie Kurttz.

Restoration romp: Tom Turner (left) and Jonathan Broadbent in Love for Love. Photo by Ellie Kurttz.

LOVE FOR LOVE

* * * *

November 4, 2015

RSC, The Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Friday, January 22, 2016

William Congreve’s Restoration comedy gets a roisterous rendition courtesy of director Selina Cadell and a talented ensemble.

For the full review visit whatsonstage.com

* * * *

November 4, 2015

RSC, The Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Friday, January 22, 2016

William Congreve’s Restoration comedy gets a roisterous rendition courtesy of director Selina Cadell and a talented ensemble.

For the full review visit whatsonstage.com

Alex Hassell as Henry V in Gregory Doran's new production. Picture by Keith Pattison.

Alex Hassell as Henry V in Gregory Doran's new production. Picture by Keith Pattison.

HENRY V

* * * *

October 2, 2015

RSC, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Sunday, October 25, 2015

THERE’S a real sense of transition in Gregory Doran’s excellent new production of Henry V at Stratford. And at the heart of it is the subtle but superbly developed performance of Alex Hassell in the title role.

Somewhat overshadowed by Antony Sher’s glorious Falstaff in the earlier history plays, Hassell’s boy-king emerges from the roisterous ne’er-do-well of his Prince Hal chrysalis into the beautifully formed butterfly of the newly-crowned king. His journey to manhood and statesmanhood continues throughout this production, marking out Hassell’s performance as thoughtful, well-judged and ultimately assertive.

Doran’s show emphasises the king’s devotion to divine right and to God, placing England (and even Wales) at the pinnacle of the medieval league table. If the French suffer as comic idiots as a result, that’s too bad – there’s no mistaking the political line in Shakespeare’s narrative. But Doran doesn’t duck the personal either, with a touching wooing scene (often a lame add-on) with the French princess Katherine (a scene-stealing Jennifer Kirby).

The strong company draw out plenty of humour, too, from the feisty Welsh captain Fluellen (Joshua Richards) to an incoherently brilliant Simon Yadoo as a Scottish officer, contrasting the muddy grimness of war with some welcome lighter touches.

Strolling through proceedings is a schoolmasterly Oliver Ford Davies as the Chorus, imploring us in rich, velvety tones to lend our imaginations to supply the battle scenes. With a constant twinkle in his eye, he’s Everyman up on stage, representing us among the conscripted soldiers and preventing the soaring language from distancing us from the harsh realities.

Stephen Brimson Lewis’s shimmering set design and costumes look fabulous, Paul Englishby’s ever-reliable score works brilliantly, and Tim Mitchell’s lighting adds atmosphere aplenty. With imposing performances from noblemen and peasants alike, it’s a Henry that sits well within the long line of Stratford greats.

* * * *

October 2, 2015

RSC, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Sunday, October 25, 2015

THERE’S a real sense of transition in Gregory Doran’s excellent new production of Henry V at Stratford. And at the heart of it is the subtle but superbly developed performance of Alex Hassell in the title role.

Somewhat overshadowed by Antony Sher’s glorious Falstaff in the earlier history plays, Hassell’s boy-king emerges from the roisterous ne’er-do-well of his Prince Hal chrysalis into the beautifully formed butterfly of the newly-crowned king. His journey to manhood and statesmanhood continues throughout this production, marking out Hassell’s performance as thoughtful, well-judged and ultimately assertive.

Doran’s show emphasises the king’s devotion to divine right and to God, placing England (and even Wales) at the pinnacle of the medieval league table. If the French suffer as comic idiots as a result, that’s too bad – there’s no mistaking the political line in Shakespeare’s narrative. But Doran doesn’t duck the personal either, with a touching wooing scene (often a lame add-on) with the French princess Katherine (a scene-stealing Jennifer Kirby).

The strong company draw out plenty of humour, too, from the feisty Welsh captain Fluellen (Joshua Richards) to an incoherently brilliant Simon Yadoo as a Scottish officer, contrasting the muddy grimness of war with some welcome lighter touches.

Strolling through proceedings is a schoolmasterly Oliver Ford Davies as the Chorus, imploring us in rich, velvety tones to lend our imaginations to supply the battle scenes. With a constant twinkle in his eye, he’s Everyman up on stage, representing us among the conscripted soldiers and preventing the soaring language from distancing us from the harsh realities.

Stephen Brimson Lewis’s shimmering set design and costumes look fabulous, Paul Englishby’s ever-reliable score works brilliantly, and Tim Mitchell’s lighting adds atmosphere aplenty. With imposing performances from noblemen and peasants alike, it’s a Henry that sits well within the long line of Stratford greats.

Derbhle Crotty as Hecuba and Ray Fearon as Agamemnon. Picture by Topher McGrillis.

Derbhle Crotty as Hecuba and Ray Fearon as Agamemnon. Picture by Topher McGrillis.

HECUBA

* * *

September 30, 2015

RSC, The Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, October 17, 2015

THERE’S a dramatic and powerful play in the story of Hecuba, the last tragic queen of Troy who watched as her family was literally dismembered in front of her by the invading Greeks. Sadly, this isn’t it.

Marina Carr’s new version for the RSC adopts the quirky, inaccessible device of having the characters explain the story in reported speech to the audience, rather than simply saying the words to each other. This disastrous decision shifts everything into a kind of detached mode, separating all the characters from their emotions and reducing the extraordinary, bloody narrative to an ancient history lesson.

Coupled with some distinctly unqueenly dialogue (“Shut it!”) and a weirdly measured pace of delivery, it begins to make the almost two-hour production – run inexplicably with no interval – feel like a Homerian epic of endurance.

The weight of the script is not aided by Erica Whyman’s static, sombre production. Soutra Gilmour’s shiny design is simple to the point of basic, with plain costumes preventing any distraction and the predominantly empty stage largely unfettered by props.

There’s refuge in the performances, though, with Ray Fearon in particularly imposing form as the Greek general Agamemnon. His stature and gravitas are impressive, commanding the stage whenever he’s on it, and he gets strong support from Chu Omambala as his lieutenant Odysseus.

The women of Troy, led by Hecuba herself, are stoic under threat. Derbhle Crotty as the eponymous queen is asked to carry insane amounts of misery – the opening scene begins with her description of sitting among the butchered remains of her children – but is prevented from fully engaging with the character’s emotions thanks to the distancing nature of the text. Nadia Albina makes another notable RSC contribution in the role of Cassandra, Hecuba’s prophetess daughter, and singer Lara Stubbs adds an unworldly dimension with some fine vocal expression in Isobel Waller-Bridge’s evocative music.

But it’s a long couple of hours of grim storytelling that leaves you longing for a bit of straightforward playwriting as a way of connecting properly with the audience.

* * *

September 30, 2015

RSC, The Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, October 17, 2015

THERE’S a dramatic and powerful play in the story of Hecuba, the last tragic queen of Troy who watched as her family was literally dismembered in front of her by the invading Greeks. Sadly, this isn’t it.

Marina Carr’s new version for the RSC adopts the quirky, inaccessible device of having the characters explain the story in reported speech to the audience, rather than simply saying the words to each other. This disastrous decision shifts everything into a kind of detached mode, separating all the characters from their emotions and reducing the extraordinary, bloody narrative to an ancient history lesson.

Coupled with some distinctly unqueenly dialogue (“Shut it!”) and a weirdly measured pace of delivery, it begins to make the almost two-hour production – run inexplicably with no interval – feel like a Homerian epic of endurance.

The weight of the script is not aided by Erica Whyman’s static, sombre production. Soutra Gilmour’s shiny design is simple to the point of basic, with plain costumes preventing any distraction and the predominantly empty stage largely unfettered by props.

There’s refuge in the performances, though, with Ray Fearon in particularly imposing form as the Greek general Agamemnon. His stature and gravitas are impressive, commanding the stage whenever he’s on it, and he gets strong support from Chu Omambala as his lieutenant Odysseus.

The women of Troy, led by Hecuba herself, are stoic under threat. Derbhle Crotty as the eponymous queen is asked to carry insane amounts of misery – the opening scene begins with her description of sitting among the butchered remains of her children – but is prevented from fully engaging with the character’s emotions thanks to the distancing nature of the text. Nadia Albina makes another notable RSC contribution in the role of Cassandra, Hecuba’s prophetess daughter, and singer Lara Stubbs adds an unworldly dimension with some fine vocal expression in Isobel Waller-Bridge’s evocative music.

But it’s a long couple of hours of grim storytelling that leaves you longing for a bit of straightforward playwriting as a way of connecting properly with the audience.

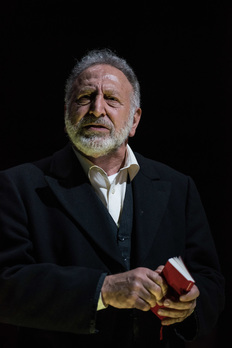

Henry Goodman's Volpone attempts to seduce a victim (Rhiannon Handy) in Trevor Nunn's production. Picture by Manuel Harlan.

Henry Goodman's Volpone attempts to seduce a victim (Rhiannon Handy) in Trevor Nunn's production. Picture by Manuel Harlan.

VOLPONE

* * *

July 11, 2015

RSC, The Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, September 12, 2015

A SATIRE on the self-serving greed of the uber-rich – what could be more apposite for our economically troubled times? A glitzy dissection of the destructive power of avarice – how pertinently entertaining. And insofar as it pokes fun at its easy targets with glee and panache, Trevor Nunn’s new production of Ben Jonson’s 400-year-old comedy is both satirical and entertaining.

But the modern-day world in which the director sets his version is not one that is easily recognisable. The sly, grasping Volpone surrounds himself with the trinkets and baubles of wealth but the victims of his cons are simply other wealthy merchants, so as an audience we’re never really bothered who ends up with the loot. Plainly, it isn’t going to be anyone deserving.

The fact that Jonson brings them all to a sorry conclusion barely makes up for the fact that, for the most part, we’re watching a bunch of scheming, unpleasant City types trying to do each other down. In the end, it all becomes a little tiresome.

There are plenty of fireworks along the way, however, and they pretty much all centre on Henry Goodman’s extraordinary Volpone. Whether he’s impersonating a sick old duffer, an Italian snake-oil salesman or a worldly-wise court officer, his versatility and bravado are breathtaking. At times, it’s like he’s channelling Robin Williams or Ronnie Barker with his range of voices and stunning array of personae. And there’s always a twinkle in the eye, a warmth that belies the unlikeable exterior of this selfish hero.

The rest of the production is clearly built around this virtuoso performance. The problem with that is that whenever he’s off-stage, the pace inevitably flags. Even the opening scene, in which he feigns terminal illness to dupe a variety of would-be heirs, runs out of steam and, like the whole show, could stand some judicious cutting.

It looks fabulous, with a stark modernist design by Stephen Brimson Lewis, and there are enjoyable performances among the supporting cast, notably Steven Pacey’s nice-but-dim toff Sir Politic Would-Be and his Essex wife (Annette McLaughlin). But the pace and tone are too uneven and the evening too long to maintain the enthusiastic energy of its star.

* * *

July 11, 2015

RSC, The Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, September 12, 2015

A SATIRE on the self-serving greed of the uber-rich – what could be more apposite for our economically troubled times? A glitzy dissection of the destructive power of avarice – how pertinently entertaining. And insofar as it pokes fun at its easy targets with glee and panache, Trevor Nunn’s new production of Ben Jonson’s 400-year-old comedy is both satirical and entertaining.

But the modern-day world in which the director sets his version is not one that is easily recognisable. The sly, grasping Volpone surrounds himself with the trinkets and baubles of wealth but the victims of his cons are simply other wealthy merchants, so as an audience we’re never really bothered who ends up with the loot. Plainly, it isn’t going to be anyone deserving.

The fact that Jonson brings them all to a sorry conclusion barely makes up for the fact that, for the most part, we’re watching a bunch of scheming, unpleasant City types trying to do each other down. In the end, it all becomes a little tiresome.

There are plenty of fireworks along the way, however, and they pretty much all centre on Henry Goodman’s extraordinary Volpone. Whether he’s impersonating a sick old duffer, an Italian snake-oil salesman or a worldly-wise court officer, his versatility and bravado are breathtaking. At times, it’s like he’s channelling Robin Williams or Ronnie Barker with his range of voices and stunning array of personae. And there’s always a twinkle in the eye, a warmth that belies the unlikeable exterior of this selfish hero.

The rest of the production is clearly built around this virtuoso performance. The problem with that is that whenever he’s off-stage, the pace inevitably flags. Even the opening scene, in which he feigns terminal illness to dupe a variety of would-be heirs, runs out of steam and, like the whole show, could stand some judicious cutting.

It looks fabulous, with a stark modernist design by Stephen Brimson Lewis, and there are enjoyable performances among the supporting cast, notably Steven Pacey’s nice-but-dim toff Sir Politic Would-Be and his Essex wife (Annette McLaughlin). But the pace and tone are too uneven and the evening too long to maintain the enthusiastic energy of its star.

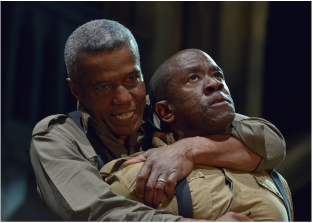

Hugh Quarshie and Lucian Msamati as Othello and Iago. Picture by Keith Pattison.

Hugh Quarshie and Lucian Msamati as Othello and Iago. Picture by Keith Pattison.

OTHELLO

* * * *

July 11, 2015

RSC, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Friday, August 28, 2015

THE notion of the outsider is a self-confessed engine behind this summer’s Stratford offerings from the RSC. We’ve already had a contentious Merchant of Venice and Jew of Malta competing to throw off the centuries-old ‘anti-Semitic’ tag. Now comes Othello, which looks to portray its study of racism in a new light by casting black actors as both the title character and his devious sidekick Iago.

Fortunately, director Iqbal Khan – who brought us a vibrant, Indian-themed Much Ado a few years back – doesn’t overplay this idea, and Hugh Quarshie and Lucian Msamati deliver terrific performances that make this colourblind casting work perfectly well, without sparking worrying questions in the viewer’s mind.

In fact, it’s their counterbalancing that provides the real drive for this considered, well-paced production. Msamati makes the most of his opportunities as Iago, dissembling and deceiving with just the right amount of venom, without ever stepping over into caricature or comedy villainy. Quarshie, meanwhile, is a thoughtful and quiet (sometimes too quiet for this big space) Othello, finding pathos as well as pigheadedness in the doomed general who’s duped into accusing his faithful wife of adultery.

Joanna Vanderham makes a stunning RSC debut as Desdemona, a subtle combination of feisty young bride and obedient wife with a fine vocal delivery and real stage presence. If you haven’t already discovered her from the BBC’s The Paradise, keep an eye on that name – she’s going to be one to watch.

Khan’s production looks sumptuous, thanks to crumbling Venetian architecture and real canals in Ciaran Bagnall’s evocative set, and the supporting ensemble offer plenty of strong interpretations, from Ayesha Dharker’s poignant maid Emilia to Jacob Fortune-Lloyd’s boyish, bemused Cassio, the unfortunate lieutenant co-accused with Desdemona.

With the emphasis on telling this powerful narrative with clarity and excitement, Khan delivers a production that explores its themes of race, jealousy and rage without allowing any one of them to dominate. It’s a fine addition to the summer season.

* * * *

July 11, 2015

RSC, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Friday, August 28, 2015

THE notion of the outsider is a self-confessed engine behind this summer’s Stratford offerings from the RSC. We’ve already had a contentious Merchant of Venice and Jew of Malta competing to throw off the centuries-old ‘anti-Semitic’ tag. Now comes Othello, which looks to portray its study of racism in a new light by casting black actors as both the title character and his devious sidekick Iago.

Fortunately, director Iqbal Khan – who brought us a vibrant, Indian-themed Much Ado a few years back – doesn’t overplay this idea, and Hugh Quarshie and Lucian Msamati deliver terrific performances that make this colourblind casting work perfectly well, without sparking worrying questions in the viewer’s mind.

In fact, it’s their counterbalancing that provides the real drive for this considered, well-paced production. Msamati makes the most of his opportunities as Iago, dissembling and deceiving with just the right amount of venom, without ever stepping over into caricature or comedy villainy. Quarshie, meanwhile, is a thoughtful and quiet (sometimes too quiet for this big space) Othello, finding pathos as well as pigheadedness in the doomed general who’s duped into accusing his faithful wife of adultery.

Joanna Vanderham makes a stunning RSC debut as Desdemona, a subtle combination of feisty young bride and obedient wife with a fine vocal delivery and real stage presence. If you haven’t already discovered her from the BBC’s The Paradise, keep an eye on that name – she’s going to be one to watch.

Khan’s production looks sumptuous, thanks to crumbling Venetian architecture and real canals in Ciaran Bagnall’s evocative set, and the supporting ensemble offer plenty of strong interpretations, from Ayesha Dharker’s poignant maid Emilia to Jacob Fortune-Lloyd’s boyish, bemused Cassio, the unfortunate lieutenant co-accused with Desdemona.

With the emphasis on telling this powerful narrative with clarity and excitement, Khan delivers a production that explores its themes of race, jealousy and rage without allowing any one of them to dominate. It’s a fine addition to the summer season.

Doomed: Catrin Stewart and Matthew Needham in Love's Sacrifice. Picture by Helen Maybanks.

Doomed: Catrin Stewart and Matthew Needham in Love's Sacrifice. Picture by Helen Maybanks.

LOVE’S SACRIFICE

* * * *

May 28, 2015

RSC, The Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Wednesday, June 24, 2015

IT’S quite possible that John Ford’s tragedy of jealousy and misplaced rage has not been professionally performed for nearly 400 years. There’s even a chance that this RSC production is a world premiere. The claim certainly adds a frisson of excitement to the unveiling of what turns out to be rather an impressive evening.

Certainly, there are parallels with Shakespeare’s rather better known tragedy of jealousy, Othello – which will be opening later this summer in the main house next door. As a curtain-raiser, Ford’s brisk, bloody potboiler has a great deal to offer. Its themes are powerful and resonate down the centuries, and director Matthew Dunster brings it entertainingly to life in his debut for the RSC.

Anna Fleischle creates a trompe l’oeil design of iron arches and stained glass that gives the impression of epic scale in the intimate confines of The Swan, and Alexander Balanescu’s underscoring music adds to the atmosphere generated by Lee Curran’s evocative lighting. Dunster keeps the pace rattling along, although the regular dumb-show vignettes are somewhat overdone and unnecessary.

Where the production scores most highly is in its performances. Catrin Stewart and Jamie Thomas King make a striking will-they-won’t-they couple at the heart of the story, tearing themselves apart in their desperate reluctance to cuckold her husband and his friend, the unfortunate Duke of Pavy (Matthew Needham). This rollercoaster emotional struggle provides the driving force for the unfolding narrative, which proceeds relentlessly and chillingly to its inevitable conclusion with verve and vitality.

Comic relief comes in the shape of Matthew Kelly’s touching but idiotic courtier Mauruccio, and the ensemble remains strong across its entirety. With surefooted confidence in their unknown but worthy source material, the company presents a show that asks one big question: why has it taken this long to surface?

* * * *

May 28, 2015

RSC, The Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Wednesday, June 24, 2015

IT’S quite possible that John Ford’s tragedy of jealousy and misplaced rage has not been professionally performed for nearly 400 years. There’s even a chance that this RSC production is a world premiere. The claim certainly adds a frisson of excitement to the unveiling of what turns out to be rather an impressive evening.

Certainly, there are parallels with Shakespeare’s rather better known tragedy of jealousy, Othello – which will be opening later this summer in the main house next door. As a curtain-raiser, Ford’s brisk, bloody potboiler has a great deal to offer. Its themes are powerful and resonate down the centuries, and director Matthew Dunster brings it entertainingly to life in his debut for the RSC.

Anna Fleischle creates a trompe l’oeil design of iron arches and stained glass that gives the impression of epic scale in the intimate confines of The Swan, and Alexander Balanescu’s underscoring music adds to the atmosphere generated by Lee Curran’s evocative lighting. Dunster keeps the pace rattling along, although the regular dumb-show vignettes are somewhat overdone and unnecessary.

Where the production scores most highly is in its performances. Catrin Stewart and Jamie Thomas King make a striking will-they-won’t-they couple at the heart of the story, tearing themselves apart in their desperate reluctance to cuckold her husband and his friend, the unfortunate Duke of Pavy (Matthew Needham). This rollercoaster emotional struggle provides the driving force for the unfolding narrative, which proceeds relentlessly and chillingly to its inevitable conclusion with verve and vitality.

Comic relief comes in the shape of Matthew Kelly’s touching but idiotic courtier Mauruccio, and the ensemble remains strong across its entirety. With surefooted confidence in their unknown but worthy source material, the company presents a show that asks one big question: why has it taken this long to surface?

Sidelined: Makram J Khoury as Shylock. Picture by Hugo Glendinning.

Sidelined: Makram J Khoury as Shylock. Picture by Hugo Glendinning.

THE MERCHANT OF VENICE

* * *

May 28, 2015

RSC, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Wednesday, September 2, 2015

THE shadow of Rupert Goold’s five-star, Las Vegas-inspired 2011 production hangs over Stratford’s main house like an intimidating older brother. But even without the sparkling memory of that extraordinary show, Polly Findlay’s latest version for the RSC would emerge as solid and sound at best.

It’s one of those productions which has the director’s stamp all over it – for better or for worse – and regular readers will know that going for the “concept” interpretation is, to this reviewer’s mind, a veritable tightrope. Goold managed it with a confident swagger; Findlay is less successful.

Her modern-day Merchant sidelines Shylock decisively, placing the titular merchant Antonio and his cross-dressing saviour Portia at the heart of the story. This, in itself, is perfectly reasonable and consistently presented. Where the problems begin to arise is in some of the more obscure directorial decisions and their consequences.

For instance, Antonio is portrayed as a fawning homosexual lover of his good friend Bassanio, whose flakiness almost leads to the unfortunate merchant’s demise. So far, so interesting. But when it comes to following through on this, with Portia’s relationship with Bassanio hanging in the balance, the compelling potential of the subtext is allowed to dissipate, and it never becomes more than a rather intriguing idea.

Elsewhere, a massive metal pendulum, set in motion early on by Portia and left to swing throughout the entire play, is never satisfactorily explained. Nor is the presence of many (but not all) of the performers on benches at the side of the stage, awaiting their entrances in solemnity – or is it boredom?

Despite its shortcomings, the production looks splendid, partly thanks to a gleaming reflective black surface on floor and walls in Johannes Shutz’s pared-back design. Patsy Ferran offers a spirited, nuanced Portia and there’s some useful supporting work from a large ensemble cast. Jamie Ballard’s Antonio is emotional and weepy, while Tim Samuels has a decent go at mining some cynical comedy from the thankless role of Launcelot Gobbo. Makram J Khoury’s Shylock, meanwhile, is underpowered and forgettable – although how much of this is down to the performance and how much to the production it’s hard to say.

For anyone coming new to the play, it’s a perfectly serviceable reading that delivers plenty of action and a clear narrative. If you saw the Goold version, it’s probably a different story.

* * *

May 28, 2015

RSC, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Wednesday, September 2, 2015

THE shadow of Rupert Goold’s five-star, Las Vegas-inspired 2011 production hangs over Stratford’s main house like an intimidating older brother. But even without the sparkling memory of that extraordinary show, Polly Findlay’s latest version for the RSC would emerge as solid and sound at best.

It’s one of those productions which has the director’s stamp all over it – for better or for worse – and regular readers will know that going for the “concept” interpretation is, to this reviewer’s mind, a veritable tightrope. Goold managed it with a confident swagger; Findlay is less successful.

Her modern-day Merchant sidelines Shylock decisively, placing the titular merchant Antonio and his cross-dressing saviour Portia at the heart of the story. This, in itself, is perfectly reasonable and consistently presented. Where the problems begin to arise is in some of the more obscure directorial decisions and their consequences.

For instance, Antonio is portrayed as a fawning homosexual lover of his good friend Bassanio, whose flakiness almost leads to the unfortunate merchant’s demise. So far, so interesting. But when it comes to following through on this, with Portia’s relationship with Bassanio hanging in the balance, the compelling potential of the subtext is allowed to dissipate, and it never becomes more than a rather intriguing idea.

Elsewhere, a massive metal pendulum, set in motion early on by Portia and left to swing throughout the entire play, is never satisfactorily explained. Nor is the presence of many (but not all) of the performers on benches at the side of the stage, awaiting their entrances in solemnity – or is it boredom?

Despite its shortcomings, the production looks splendid, partly thanks to a gleaming reflective black surface on floor and walls in Johannes Shutz’s pared-back design. Patsy Ferran offers a spirited, nuanced Portia and there’s some useful supporting work from a large ensemble cast. Jamie Ballard’s Antonio is emotional and weepy, while Tim Samuels has a decent go at mining some cynical comedy from the thankless role of Launcelot Gobbo. Makram J Khoury’s Shylock, meanwhile, is underpowered and forgettable – although how much of this is down to the performance and how much to the production it’s hard to say.

For anyone coming new to the play, it’s a perfectly serviceable reading that delivers plenty of action and a clear narrative. If you saw the Goold version, it’s probably a different story.

Twinkle: Jasper Britton as The Jew of Malta. Picture by Ellie Kurtz.

Twinkle: Jasper Britton as The Jew of Malta. Picture by Ellie Kurtz.

THE JEW OF MALTA

* * * *

April 25, 2015

RSC, The Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Tuesday, September 8, 2015

FORGET any worries about anti-Semitism in this 400-year-old Christopher Marlowe tragedy. RSC debutant director Justin Audibert renders it thrillingly up to date by drawing out its universal themes of greed, revenge and casual racism. Yes, the eponymous Jew has an evil streak a mile wide, but his deceitfulness and treachery are more than matched by the Christians and Turks who attack him.

The glee with which these are played out by a vibrant cast contribute much to the overall success of the production. It rarely stands still to draw breath, let alone meditate on the unfolding drama. Instead, Marlowe and Audibert give us relentless action, implausible plot twists and a thundering thriller of political intrigue and personal vengeance.

The whole show hinges on its central performance, and Jasper Britton hurls himself at the role of Barabas with brilliantly controlled recklessness. His energy and raw power are constantly gripping, lurching from emotion to emotion as he’s first stripped of his wealth by Malta’s governor to pay off the marauding Turkish army, then abandoned by the daughter he’s just tricked, and finally betrayed by those closest to him.

Britton has a mean twinkle in his eye, but it’s far from a one-man show. Steven Pacey is a finely aristocratic Maltese governor Ferneze, Catrin Stewart a judicious mixture of brittle and bold as Barabas’s daughter Abigail, while Geoffrey Freshwater and Matthew Kelly offer an enjoyable matching pair of Friars niggling each other over her potential conversion.

Lily Arnold’s simple stone wall design is well used and effective, and Oliver Fenwick’s lighting and Jonathan Girling’s atmospheric music add considerably to the effectiveness of the storytelling. The decision to play in Elizabethan costume and period proves a wise one, allowing Marlowe’s verse and the complex narrative plenty of room to speak for themselves, while also giving the drama an entirely appropriate context.

In a witty opening, the prologue is delivered by a man in a T-shirt that sports a logo reading RMC – Royal Marlowe Company. With productions as entertaining as this, you do start to wonder whether things might have worked out a little differently…

* * * *

April 25, 2015

RSC, The Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Tuesday, September 8, 2015

FORGET any worries about anti-Semitism in this 400-year-old Christopher Marlowe tragedy. RSC debutant director Justin Audibert renders it thrillingly up to date by drawing out its universal themes of greed, revenge and casual racism. Yes, the eponymous Jew has an evil streak a mile wide, but his deceitfulness and treachery are more than matched by the Christians and Turks who attack him.

The glee with which these are played out by a vibrant cast contribute much to the overall success of the production. It rarely stands still to draw breath, let alone meditate on the unfolding drama. Instead, Marlowe and Audibert give us relentless action, implausible plot twists and a thundering thriller of political intrigue and personal vengeance.

The whole show hinges on its central performance, and Jasper Britton hurls himself at the role of Barabas with brilliantly controlled recklessness. His energy and raw power are constantly gripping, lurching from emotion to emotion as he’s first stripped of his wealth by Malta’s governor to pay off the marauding Turkish army, then abandoned by the daughter he’s just tricked, and finally betrayed by those closest to him.

Britton has a mean twinkle in his eye, but it’s far from a one-man show. Steven Pacey is a finely aristocratic Maltese governor Ferneze, Catrin Stewart a judicious mixture of brittle and bold as Barabas’s daughter Abigail, while Geoffrey Freshwater and Matthew Kelly offer an enjoyable matching pair of Friars niggling each other over her potential conversion.

Lily Arnold’s simple stone wall design is well used and effective, and Oliver Fenwick’s lighting and Jonathan Girling’s atmospheric music add considerably to the effectiveness of the storytelling. The decision to play in Elizabethan costume and period proves a wise one, allowing Marlowe’s verse and the complex narrative plenty of room to speak for themselves, while also giving the drama an entirely appropriate context.

In a witty opening, the prologue is delivered by a man in a T-shirt that sports a logo reading RMC – Royal Marlowe Company. With productions as entertaining as this, you do start to wonder whether things might have worked out a little differently…

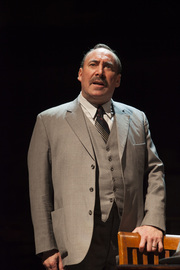

Triumph: Antony Sher as Willy Loman. Picture by Ellie Kurtz.

Triumph: Antony Sher as Willy Loman. Picture by Ellie Kurtz.

DEATH OF A SALESMAN

* * * *

April 25, 2015

RSC, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, May 2, 2015, then transferring to the Noel Coward Theatre, London, until Saturday, July 18, 2015

Marking the centenary of Arthur Miller’s birth, RSC artistic director Gregory Doran takes perhaps his most iconic protagonist, Willy Loman, and places him centre stage in the Royal Shakespeare Theatre. For such a little man, with little to show for his life, it’s a bold step.

But Willy’s dreams are big. They’ve always been big. Now, in the twilight of his career as a salesman, he’s forced to contemplate his own mortality and the notion of transferring his own dreams onto his unwilling sons Biff and Happy, all the while watched and implicitly supported by his long-suffering wife Linda.

Although plenty of ancillary characters come and go in Doran’s immaculately constructed production, it’s this central family quartet that grabs the attention from the outset and never lets go. Stephen Brimson Lewis’s inventive and versatile design renders their home claustrophobic and quietly intimidating, while opening out cleverly for the scenes from Willy’s memory or set in the outside world.

Alex Hassell and Sam Marks manage the difficult feat of delivering Willy’s sons as both grown-ups and gawky teenagers, and they play off each other as highly believable siblings. Harriet Walter is deceptively straightforward and dignified as their loyal mother, ready to spring to the fierce defence of her husband when required.

The real triumph, though, is Antony Sher’s performance as Willy. Utterly credible as a washed-up has-been desperately clinging to the fabricated futility he’s created for himself, Sher is achingly moving, whether he’s giving his boys a paternal pep talk or convincing himself that suicide is the best option for everyone.

And at the height of his greatest vulnerability, just when you think he’s finally realised that his life is not everything he claims it to be, suddenly he reaches deep inside for one more bash at self-deception. It raises a bitter, agonised laugh of astonishment from the audience.

It’s a towering performance in a powerful production. Whether Miller intended it to be quite as bleak and nihilistic as it’s presented here is debatable, and it’s this pessimism which slightly takes the edge off Doran’s revival, but its well-deserved transfer to London will allow plenty more people to be the judge.

* * * *

April 25, 2015

RSC, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, May 2, 2015, then transferring to the Noel Coward Theatre, London, until Saturday, July 18, 2015

Marking the centenary of Arthur Miller’s birth, RSC artistic director Gregory Doran takes perhaps his most iconic protagonist, Willy Loman, and places him centre stage in the Royal Shakespeare Theatre. For such a little man, with little to show for his life, it’s a bold step.

But Willy’s dreams are big. They’ve always been big. Now, in the twilight of his career as a salesman, he’s forced to contemplate his own mortality and the notion of transferring his own dreams onto his unwilling sons Biff and Happy, all the while watched and implicitly supported by his long-suffering wife Linda.

Although plenty of ancillary characters come and go in Doran’s immaculately constructed production, it’s this central family quartet that grabs the attention from the outset and never lets go. Stephen Brimson Lewis’s inventive and versatile design renders their home claustrophobic and quietly intimidating, while opening out cleverly for the scenes from Willy’s memory or set in the outside world.

Alex Hassell and Sam Marks manage the difficult feat of delivering Willy’s sons as both grown-ups and gawky teenagers, and they play off each other as highly believable siblings. Harriet Walter is deceptively straightforward and dignified as their loyal mother, ready to spring to the fierce defence of her husband when required.

The real triumph, though, is Antony Sher’s performance as Willy. Utterly credible as a washed-up has-been desperately clinging to the fabricated futility he’s created for himself, Sher is achingly moving, whether he’s giving his boys a paternal pep talk or convincing himself that suicide is the best option for everyone.

And at the height of his greatest vulnerability, just when you think he’s finally realised that his life is not everything he claims it to be, suddenly he reaches deep inside for one more bash at self-deception. It raises a bitter, agonised laugh of astonishment from the audience.

It’s a towering performance in a powerful production. Whether Miller intended it to be quite as bleak and nihilistic as it’s presented here is debatable, and it’s this pessimism which slightly takes the edge off Doran’s revival, but its well-deserved transfer to London will allow plenty more people to be the judge.

John Heffernan in the title role of Oppenheimer. Picture by Keith Pattison.

John Heffernan in the title role of Oppenheimer. Picture by Keith Pattison.

OPPENHEIMER

* * * *

January 23, 2015

RSC, The Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, March 7, 2015

PLAYWRIGHT Tom Morton-Smith has taken an epic tale of war, politics and conspiracy and delivered a highly-charged, personal story of moral dilemmas, emotional trauma and ultimate tragedy.

How the charismatic J Robert Oppenheimer came to lead a team of vagabond scientists to develop the atom bomb that ended World War Two is not a revelation, and this new play brings little in the way of fresh information. What it has aplenty, however, is the domestic drama that accompanied the big story behind the scenes, including adultery, ambition and an alarming lack of scruples.

Morton-Smith’s taut and gripping script is well served by director Angus Jackson and a terrific, utterly believable ensemble cast, led by the extraordinary John Heffernan in the title role. At times pleasantly affable, he’s prone to launch into a look of startling intensity that reveals as much about the enigmatic Oppenheimer as any of his grandstanding speeches.

William Gaminara is in excellent form as the US Army General charged with keeping the wayward, possibly Communist-sympathising scientists on task, while Thomasin Rand and Catherine Steadman as Oppenheimer’s wife and lover respectively bring real humanity to their roles, struggling to find a place in his life alongside the all-consuming Manhattan project.

A simple but effective set by Robert Innes Hopkins makes superb use of The Swan’s space and Grant Olding’s 1940s-influenced score adds considerable texture to what is a thrilling retelling of event history with more than a dash of political intrigue and individual drive.

* * * *

January 23, 2015

RSC, The Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until Saturday, March 7, 2015

PLAYWRIGHT Tom Morton-Smith has taken an epic tale of war, politics and conspiracy and delivered a highly-charged, personal story of moral dilemmas, emotional trauma and ultimate tragedy.

How the charismatic J Robert Oppenheimer came to lead a team of vagabond scientists to develop the atom bomb that ended World War Two is not a revelation, and this new play brings little in the way of fresh information. What it has aplenty, however, is the domestic drama that accompanied the big story behind the scenes, including adultery, ambition and an alarming lack of scruples.

Morton-Smith’s taut and gripping script is well served by director Angus Jackson and a terrific, utterly believable ensemble cast, led by the extraordinary John Heffernan in the title role. At times pleasantly affable, he’s prone to launch into a look of startling intensity that reveals as much about the enigmatic Oppenheimer as any of his grandstanding speeches.

William Gaminara is in excellent form as the US Army General charged with keeping the wayward, possibly Communist-sympathising scientists on task, while Thomasin Rand and Catherine Steadman as Oppenheimer’s wife and lover respectively bring real humanity to their roles, struggling to find a place in his life alongside the all-consuming Manhattan project.

A simple but effective set by Robert Innes Hopkins makes superb use of The Swan’s space and Grant Olding’s 1940s-influenced score adds considerable texture to what is a thrilling retelling of event history with more than a dash of political intrigue and individual drive.

For Stratford reviews from 2016, please click here

For Stratford reviews from 2014, please click here

For Stratford reviews from 2013, please click here

For Stratford reviews from 2012, please click here

For Stratford reviews from 2011, please click here

For Stratford reviews from 2010, please click here

For Stratford reviews from 2009, please click here

For Stratford reviews from 2008, please click here