THE SNOW QUEEN

* * * *

November 27, 2015

Royal Theatre, Northampton, until Sunday, January 3, 2015

Director Gary Sefton brings his magical touch to another Northampton Christmas treat. For the full review visit whatsonstage.com

* * * *

November 27, 2015

Royal Theatre, Northampton, until Sunday, January 3, 2015

Director Gary Sefton brings his magical touch to another Northampton Christmas treat. For the full review visit whatsonstage.com

Tara Fitzgerald and Jonathan Firth as Bella and Jack Manningham in Gaslight. Photo by Idil Sukan/Draw HQ.

Tara Fitzgerald and Jonathan Firth as Bella and Jack Manningham in Gaslight. Photo by Idil Sukan/Draw HQ.

GASLIGHT

* * * *

October 23, 2015

Royal Theatre, Northampton, until Saturday, November 7, 2015

THE setting for Patrick Hamilton’s Victorian-era thriller could hardly be more perfect: Northampton’s atmospheric Royal Theatre was built in 1888, within a decade of the sinister goings-on that are played out in this psychological masterpiece.

But the environment is just one of many things that this intelligent, exciting production has going for it. Director Lucy Bailey has assembled a formidable team around her – including trusty designer William Dudley, composer Nell Catchpole and stars Tara Fitzgerald and Jonathan Firth – to create an evening of memorable impact and considerable drama.

Dudley’s magnificent set exploits the confines of the Royal’s claustrophobic stage, with perspectives skewed and the sloping ceiling suddenly giving way to impressive video projections at strategic points. I did wonder about potential sightlines from many areas of the auditorium, but from the second row of the Circle it all worked brilliantly.

The psychological tussles between Fitzgerald and Firth, too, are emphatically a success. It’s easy to see how Hamilton’s dialogue, written in the 1930s, could sound stilted and strange to modern ears, but the pair both find meaning and sense in their repeated phrases and awkwardly-constructed sentences, adding a layer of additional complexity to the already tangled relationship between them.

Without giving away crucial plot twists, Fitzgerald evokes Bella Manningham’s descent into madness with acuity and painful realism, while Firth, as her husband Jack, lurches persuasively from charm personified to terrifying intimidation at a moment’s notice. Their devastating interactions lie at the heart of this powerful production, and Bailey quite rightly gives them full throttle.

Personally, I could have done without some of the more melodramatic touches, and Paul Hunter’s eccentric performance as Inspector Rough, the mysterious policeman who steps in to reveal the crucial backstory, veers far to close to comic caricature for my taste, sitting at odds with the production’s overall tone.

But there’s enough menace and imagination on offer to qualify this as a solid, entertaining version of Hamilton’s classic play, well worth the quality outing it’s given here.

* * * *

October 23, 2015

Royal Theatre, Northampton, until Saturday, November 7, 2015

THE setting for Patrick Hamilton’s Victorian-era thriller could hardly be more perfect: Northampton’s atmospheric Royal Theatre was built in 1888, within a decade of the sinister goings-on that are played out in this psychological masterpiece.

But the environment is just one of many things that this intelligent, exciting production has going for it. Director Lucy Bailey has assembled a formidable team around her – including trusty designer William Dudley, composer Nell Catchpole and stars Tara Fitzgerald and Jonathan Firth – to create an evening of memorable impact and considerable drama.

Dudley’s magnificent set exploits the confines of the Royal’s claustrophobic stage, with perspectives skewed and the sloping ceiling suddenly giving way to impressive video projections at strategic points. I did wonder about potential sightlines from many areas of the auditorium, but from the second row of the Circle it all worked brilliantly.

The psychological tussles between Fitzgerald and Firth, too, are emphatically a success. It’s easy to see how Hamilton’s dialogue, written in the 1930s, could sound stilted and strange to modern ears, but the pair both find meaning and sense in their repeated phrases and awkwardly-constructed sentences, adding a layer of additional complexity to the already tangled relationship between them.

Without giving away crucial plot twists, Fitzgerald evokes Bella Manningham’s descent into madness with acuity and painful realism, while Firth, as her husband Jack, lurches persuasively from charm personified to terrifying intimidation at a moment’s notice. Their devastating interactions lie at the heart of this powerful production, and Bailey quite rightly gives them full throttle.

Personally, I could have done without some of the more melodramatic touches, and Paul Hunter’s eccentric performance as Inspector Rough, the mysterious policeman who steps in to reveal the crucial backstory, veers far to close to comic caricature for my taste, sitting at odds with the production’s overall tone.

But there’s enough menace and imagination on offer to qualify this as a solid, entertaining version of Hamilton’s classic play, well worth the quality outing it’s given here.

Gruffud Glyn as Bernard and William Postlethwaite as John the Savage in Brave New World. Picture by Manuel Harlon.

Gruffud Glyn as Bernard and William Postlethwaite as John the Savage in Brave New World. Picture by Manuel Harlon.

BRAVE NEW WORLD

* * * *

September 11, 2015

Royal Theatre, Northampton, until Saturday September 26, 2015, then touring until Saturday, December 5, 2015

PRESCIENT dystopian shows are all over the place at the moment. Maybe it’s something in the political air, but theatres are latching onto the resonance of authors from Kafka to Orwell. So it was probably only a matter of time before Aldous Huxley’s 1930s sci-fi thriller made it to the stage.

In Dawn King’s new adaptation for Royal & Derngate and the Touring Consortium, it emerges as a claustrophobic, sinister and threatening piece in which individual freedoms and personalities are heavily censored and controlled by a supreme world state. Pre-programmed embryos are created to lead, work or serve in drudgery, yet all remain happy thanks to the omnipresent legal drug Soma.

So when a naturally-born outsider from the “savage reservation” beyond the state borders is introduced as a kind of experimental oddity, it’s not just the order of things, but personal happiness that’s at stake.

With such a complex world to introduce, there’s a strong element of information download through the first half of the play. King employs the notion of the genetic control centre’s director taking the audience on a guided tour of his facility to get the details across, but inevitably it’s hard going to begin with. Fortunately, things pick up significantly when the focus shifts to a handful of individuals, notably staff members Bernard and Lenina.

It’s the personal struggles that make or break this potentially sterile story, and Gruffudd Glyn and Olivia Morgan bring these two characters to vivid life. Joining them later in their journey of discovery is John the Savage (William Postlethwaite), earthy and questioning as the human timebomb whose liberal quotation of Shakespeare undermines the stability of the state.

Once the introductions are out of the way, director James Dacre’s production moves pacily through its developing story, keeping things heading rapidly towards their tragic conclusion, and his cast of ten adopt a host of characters to maintain a feeling of thronging impersonality.

There’s a real sense of interwoven skills at work, too, with some intelligent but not overused video designs by Keith Skretch and some vaguely intimidating but highly effective underscored music by These New Puritans. Designer Naomi Dawson brings the threads together with a versatile set that encompasses everything from a flying vehicle to a soulless nightclub, all serving the narrative rather than trying to be clever or tricksy in their own right.

It’s an ambitious project that aims to bring Huxley’s classic nightmare vision to new generations as it tours the country between now and December. Its message is as chilling as when it was first written, and it deserves to be heard in our modern brave new world.

* * * *

September 11, 2015

Royal Theatre, Northampton, until Saturday September 26, 2015, then touring until Saturday, December 5, 2015

PRESCIENT dystopian shows are all over the place at the moment. Maybe it’s something in the political air, but theatres are latching onto the resonance of authors from Kafka to Orwell. So it was probably only a matter of time before Aldous Huxley’s 1930s sci-fi thriller made it to the stage.

In Dawn King’s new adaptation for Royal & Derngate and the Touring Consortium, it emerges as a claustrophobic, sinister and threatening piece in which individual freedoms and personalities are heavily censored and controlled by a supreme world state. Pre-programmed embryos are created to lead, work or serve in drudgery, yet all remain happy thanks to the omnipresent legal drug Soma.

So when a naturally-born outsider from the “savage reservation” beyond the state borders is introduced as a kind of experimental oddity, it’s not just the order of things, but personal happiness that’s at stake.

With such a complex world to introduce, there’s a strong element of information download through the first half of the play. King employs the notion of the genetic control centre’s director taking the audience on a guided tour of his facility to get the details across, but inevitably it’s hard going to begin with. Fortunately, things pick up significantly when the focus shifts to a handful of individuals, notably staff members Bernard and Lenina.

It’s the personal struggles that make or break this potentially sterile story, and Gruffudd Glyn and Olivia Morgan bring these two characters to vivid life. Joining them later in their journey of discovery is John the Savage (William Postlethwaite), earthy and questioning as the human timebomb whose liberal quotation of Shakespeare undermines the stability of the state.

Once the introductions are out of the way, director James Dacre’s production moves pacily through its developing story, keeping things heading rapidly towards their tragic conclusion, and his cast of ten adopt a host of characters to maintain a feeling of thronging impersonality.

There’s a real sense of interwoven skills at work, too, with some intelligent but not overused video designs by Keith Skretch and some vaguely intimidating but highly effective underscored music by These New Puritans. Designer Naomi Dawson brings the threads together with a versatile set that encompasses everything from a flying vehicle to a soulless nightclub, all serving the narrative rather than trying to be clever or tricksy in their own right.

It’s an ambitious project that aims to bring Huxley’s classic nightmare vision to new generations as it tours the country between now and December. Its message is as chilling as when it was first written, and it deserves to be heard in our modern brave new world.

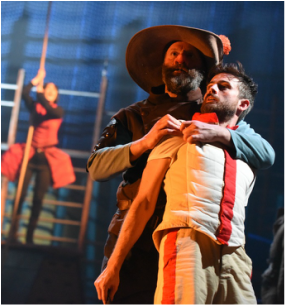

Jamie Sives as Marty, with Joe Alessi (behind) as his nemesis Louis in The Hook. Picture by Manuel Harlan.

Jamie Sives as Marty, with Joe Alessi (behind) as his nemesis Louis in The Hook. Picture by Manuel Harlan.

THE HOOK

* * *

June 11, 2015

Royal Theatre, Northampton, until Saturday June 27, 2015, then transfers to Liverpool Everyman from Wednesday, July 1, to Saturday, July 25, 2015

IT’S intriguing to be treated to the world premiere of a new play ten years after its author’s demise. Thanks to some detective work by artistic director James Dacre and some crafty assemblage by Hollywood veteran scriptwriter Ron Hutchinson, the Royal Theatre is doing exactly that with this Arthur Miller piece, marking the centenary of his birth.

Originally written as a “play for the screen” but never filmed – partly due to Miller’s falling out with its director Elia Kazan over the notorious McCarthy witchhunt trials in the 1950s – it makes a rather uneasy transition to the stage, with a succession of filmic, disjointed scenes playing out against a nicely realised dockside set by designer Patrick Connellan.

But it’s easy to trace the themes of individual integrity versus the greater good, and the evils and iniquities of institutionalised criminality, in some of Miller’s other, better known works. Within two years, he would write The Crucible, and its protagonist John Proctor is templated in a different form here.

In the New York waterfront setting of The Hook, Marty Ferrara is the decent man wanting to earn a wage for an honest day’s work. When the racketeering and gangsterism of the union bosses threatens the livelihood of him and his colleagues, he’s driven to take dramatic and drastic action in the name of the wider struggle – regardless of its individual consequences for him.

The character’s motivations and decisions are clearly drawn out in Dacre’s meaty production, atmospherically lit by Charles Balfour and with a muscular musical underscore from Isobel Waller-Bridge. Supplemented by a large community ensemble, the cast of 11 provide a thronging, urgent mass of disaffected working-class bruisers with an intimidating menace lurking constantly below the surface.

Jamie Sives’s Ferrara takes some adjusting to, with a thick accent that makes him frequently hard to understand, but the sense of unfairness and barely-controlled anger he displays are palpable. Joe Alessi is outstanding as his nemesis, the union leader Louis, and there are some fine supporting performances among the other longshoremen, divided over whether to back their new spokesman or play it safe for the sake of their jobs.

It all gets a bit shouty at times, and the first half isn’t quite as punchy as the second, but Hutchinson’s adherence to the original screenplay’s dialogue and intentions creates a script that makes a fascinating addition to the Miller catalogue.

* * *

June 11, 2015

Royal Theatre, Northampton, until Saturday June 27, 2015, then transfers to Liverpool Everyman from Wednesday, July 1, to Saturday, July 25, 2015

IT’S intriguing to be treated to the world premiere of a new play ten years after its author’s demise. Thanks to some detective work by artistic director James Dacre and some crafty assemblage by Hollywood veteran scriptwriter Ron Hutchinson, the Royal Theatre is doing exactly that with this Arthur Miller piece, marking the centenary of his birth.

Originally written as a “play for the screen” but never filmed – partly due to Miller’s falling out with its director Elia Kazan over the notorious McCarthy witchhunt trials in the 1950s – it makes a rather uneasy transition to the stage, with a succession of filmic, disjointed scenes playing out against a nicely realised dockside set by designer Patrick Connellan.

But it’s easy to trace the themes of individual integrity versus the greater good, and the evils and iniquities of institutionalised criminality, in some of Miller’s other, better known works. Within two years, he would write The Crucible, and its protagonist John Proctor is templated in a different form here.

In the New York waterfront setting of The Hook, Marty Ferrara is the decent man wanting to earn a wage for an honest day’s work. When the racketeering and gangsterism of the union bosses threatens the livelihood of him and his colleagues, he’s driven to take dramatic and drastic action in the name of the wider struggle – regardless of its individual consequences for him.

The character’s motivations and decisions are clearly drawn out in Dacre’s meaty production, atmospherically lit by Charles Balfour and with a muscular musical underscore from Isobel Waller-Bridge. Supplemented by a large community ensemble, the cast of 11 provide a thronging, urgent mass of disaffected working-class bruisers with an intimidating menace lurking constantly below the surface.

Jamie Sives’s Ferrara takes some adjusting to, with a thick accent that makes him frequently hard to understand, but the sense of unfairness and barely-controlled anger he displays are palpable. Joe Alessi is outstanding as his nemesis, the union leader Louis, and there are some fine supporting performances among the other longshoremen, divided over whether to back their new spokesman or play it safe for the sake of their jobs.

It all gets a bit shouty at times, and the first half isn’t quite as punchy as the second, but Hutchinson’s adherence to the original screenplay’s dialogue and intentions creates a script that makes a fascinating addition to the Miller catalogue.

Feisty: Charlie Brooks with Sam Jackson, left, and Thomas Law.

Picture by Anton Belmonte.

Feisty: Charlie Brooks with Sam Jackson, left, and Thomas Law.

Picture by Anton Belmonte.

BEAUTIFUL THING

* * *

May 18, 2015

Royal Theatre, Northampton, until Saturday, May 23, 2015, then tour continues

IT’S 20 years since Jonathan Harvey’s coming-of-age love story between two teenage boys on a south London sink estate premiered at the Bush Theatre. A lot has changed in the world of gay rights since then, which turns Nikolai Foster’s pacy revival into something of a period piece.

That’s not to say it doesn’t have a lot to offer as a tender, amusing observation of blossoming first love, but it doesn’t feel like the groundbreaking play it once must have done. Instead, it’s a gently entertaining slice of life that wouldn’t feel out of place as an EastEnders special – and that’s intended as a compliment.

The real strength of the production is in its performances. Charlie Brooks – herself no stranger to EastEnders, of course – is in blistering form as Sandra, the feisty, no-nonsense mum whose love for her 15-year-old son Jamie shows up in some interesting ways, but who is pivotal to the piece’s ultimately uplifting ending. We already know Ms Brooks can do gutsy and gritty, but she reveals a surprisingly warm and tender side too, and is consistently watchable.

Sam Jackson is touching and vulnerable as her son, with some excellent work between him and Thomas Law as the neighbour’s lad with whom he falls almost accidentally in love. Their scenes together are believable and moving, with Harvey’s typical humour leavening the mix.

Director Foster really knows how to spin a yarn with his raw material, and the accompanying design by Colin Richmond provides an appropriately downbeat setting for the love-among-the-council-flats story. The music of Mama Cass supplies an intermittent soundtrack as the scenes play out, although the piece occasionally suffers from a slight lack of forward momentum, robbing it of some of its potential for emotional impact.

A co-production involving Leicester’s Curve and Nottingham Playhouse, Beautiful Thing certainly merits another airing. Whether it will find a sizeable audience as the tour continues remains to be seen, but those who witnessed its Northampton outing were enthusiastic and vociferous.

* * *

May 18, 2015

Royal Theatre, Northampton, until Saturday, May 23, 2015, then tour continues

IT’S 20 years since Jonathan Harvey’s coming-of-age love story between two teenage boys on a south London sink estate premiered at the Bush Theatre. A lot has changed in the world of gay rights since then, which turns Nikolai Foster’s pacy revival into something of a period piece.

That’s not to say it doesn’t have a lot to offer as a tender, amusing observation of blossoming first love, but it doesn’t feel like the groundbreaking play it once must have done. Instead, it’s a gently entertaining slice of life that wouldn’t feel out of place as an EastEnders special – and that’s intended as a compliment.

The real strength of the production is in its performances. Charlie Brooks – herself no stranger to EastEnders, of course – is in blistering form as Sandra, the feisty, no-nonsense mum whose love for her 15-year-old son Jamie shows up in some interesting ways, but who is pivotal to the piece’s ultimately uplifting ending. We already know Ms Brooks can do gutsy and gritty, but she reveals a surprisingly warm and tender side too, and is consistently watchable.

Sam Jackson is touching and vulnerable as her son, with some excellent work between him and Thomas Law as the neighbour’s lad with whom he falls almost accidentally in love. Their scenes together are believable and moving, with Harvey’s typical humour leavening the mix.

Director Foster really knows how to spin a yarn with his raw material, and the accompanying design by Colin Richmond provides an appropriately downbeat setting for the love-among-the-council-flats story. The music of Mama Cass supplies an intermittent soundtrack as the scenes play out, although the piece occasionally suffers from a slight lack of forward momentum, robbing it of some of its potential for emotional impact.

A co-production involving Leicester’s Curve and Nottingham Playhouse, Beautiful Thing certainly merits another airing. Whether it will find a sizeable audience as the tour continues remains to be seen, but those who witnessed its Northampton outing were enthusiastic and vociferous.

Delicate balance: Jo Stone-Fewings as King John. Picture by Marc Brenner.

Delicate balance: Jo Stone-Fewings as King John. Picture by Marc Brenner.

KING JOHN

* * * *

April 28, 2015

Holy Sepulchre Church, Northampton, until Saturday, May 16, 2015, then transferring to Shakespeare’s Globe

THE ambition of this co-production between Royal & Derngate and Shakespeare’s Globe can hardly be faulted. Putting Shakespeare’s least popular history play on a temporary stage in one of the few round churches in the country – a church King John himself would have known – and lighting it primarily by candlelight is a bold decision.

And, for the most part, director James Dacre makes it work thrillingly. Played in a traverse format down the straight nave of ‘St Sep’s’, the battling factions in English red and French green make for a literally in-yer-face experience. Philip the Bastard, exhilaratingly portrayed by RSC veteran Alex Waldmann, chats his asides to the three rows of pews lining the performance space. Escaping from high battlements, young Prince Arthur (an accomplished Laurence Belcher) ends up dead at your feet, with grieving knights weeping in alarming close-up an arm’s length away.

There are inevitable problems with this innovative staging. There’s a bit of a tennis match feeling as you twist to see from one end of the space to another; to fill the lofty vaults of the church, much of the verse delivery is, by necessity, a bit shouty; and whether the run will reach a safe conclusion without an audience member being unwittingly skewered in one of the visceral, terrifying battle sequences remains to be seen.

But the vitality and vivid, shocking immediacy of the performances win hands down over the disadvantages. Jonathan Fensom’s medieval period design works spectacularly well and the ease with which we are transported back eight centuries is a major accomplishment. The candlelight helps, although acting nuances are lost in the dimness, and Orlando Gough’s ethereal music – played anachronistically on instruments ranging from saxophone and harmonica to accordion and drums – adds considerable texture, even if the sung passages are heavily overused.

Dacre wisely concentrates on unfolding his narrative, and the result is clear and highly intelligible, raising the question of why this lesser known offering isn’t done more often. Appropriate and effective use is made of the church’s organ and bells, and there’s a stunning tableau of old King Richard’s funeral that greets the arriving audience at the outset in the circular part of the church.

The performances are uniformly strong, with Jo Stone-Fewings giving a delicate balance of divine right and weak humanity in the title role. Barbara Marten is impressive and impassioned as his mother Eleanor, while Tanya Moodie offers a moving interpretation of grief in the face of implacable authority as the wronged mother of the royal claimant Arthur. Mark Meadows is a surprisingly touching Hubert, ducking out of murdering his young ward with honour and emotional credibility, and professional debutante Aruhan Galieva suggests there’s much more in store from her future career.

With performances at the Globe fast selling out, this is a rare chance to see Shakespeare of the highest quality in a unique setting. For all its foibles, it’s a production definitely worth catching.

* * * *

April 28, 2015

Holy Sepulchre Church, Northampton, until Saturday, May 16, 2015, then transferring to Shakespeare’s Globe

THE ambition of this co-production between Royal & Derngate and Shakespeare’s Globe can hardly be faulted. Putting Shakespeare’s least popular history play on a temporary stage in one of the few round churches in the country – a church King John himself would have known – and lighting it primarily by candlelight is a bold decision.

And, for the most part, director James Dacre makes it work thrillingly. Played in a traverse format down the straight nave of ‘St Sep’s’, the battling factions in English red and French green make for a literally in-yer-face experience. Philip the Bastard, exhilaratingly portrayed by RSC veteran Alex Waldmann, chats his asides to the three rows of pews lining the performance space. Escaping from high battlements, young Prince Arthur (an accomplished Laurence Belcher) ends up dead at your feet, with grieving knights weeping in alarming close-up an arm’s length away.

There are inevitable problems with this innovative staging. There’s a bit of a tennis match feeling as you twist to see from one end of the space to another; to fill the lofty vaults of the church, much of the verse delivery is, by necessity, a bit shouty; and whether the run will reach a safe conclusion without an audience member being unwittingly skewered in one of the visceral, terrifying battle sequences remains to be seen.

But the vitality and vivid, shocking immediacy of the performances win hands down over the disadvantages. Jonathan Fensom’s medieval period design works spectacularly well and the ease with which we are transported back eight centuries is a major accomplishment. The candlelight helps, although acting nuances are lost in the dimness, and Orlando Gough’s ethereal music – played anachronistically on instruments ranging from saxophone and harmonica to accordion and drums – adds considerable texture, even if the sung passages are heavily overused.

Dacre wisely concentrates on unfolding his narrative, and the result is clear and highly intelligible, raising the question of why this lesser known offering isn’t done more often. Appropriate and effective use is made of the church’s organ and bells, and there’s a stunning tableau of old King Richard’s funeral that greets the arriving audience at the outset in the circular part of the church.

The performances are uniformly strong, with Jo Stone-Fewings giving a delicate balance of divine right and weak humanity in the title role. Barbara Marten is impressive and impassioned as his mother Eleanor, while Tanya Moodie offers a moving interpretation of grief in the face of implacable authority as the wronged mother of the royal claimant Arthur. Mark Meadows is a surprisingly touching Hubert, ducking out of murdering his young ward with honour and emotional credibility, and professional debutante Aruhan Galieva suggests there’s much more in store from her future career.

With performances at the Globe fast selling out, this is a rare chance to see Shakespeare of the highest quality in a unique setting. For all its foibles, it’s a production definitely worth catching.

Nigel Barett leads the cast of Cyrano. Picture by Robert Day.

Nigel Barett leads the cast of Cyrano. Picture by Robert Day.

CYRANO DE BERGERAC

* * *

April 9, 2015

Royal Theatre, Northampton, until Saturday April 25, 2015, then transfers to Northern Stage from Wednesday, April 29, to Saturday, May 16, 2015

THE story of the 17th Century poet-soldier with the whopping conk has proved popular in a multitude of artforms since it was first performed more than 100 years ago. Sometimes dubbed the most romantic play ever written, its theme of unrequited love and poignant tragedy tugs at the heartstrings.

Royal & Derngate have teamed up with Northern Stage again after last year’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof to produce this new version of Anthony Burgess’s 1971 clever rhyming couplet translation of Edmond Rostand’s French original. It’s a bold, ambitious production but for me, many of the directorial decisions – helmed by Northern Stage’s Lorne Campbell – seem strangely misguided.

Set unaccountably in a gymnasium in some indeterminate time period, the action plays out among monkey bars, sporting equipment and raked plastic seating. There’s a boxing ring-style microphone that’s used occasionally and randomly, and an ensemble of young supporting players are dressed, for some unexplained reason, in fencing gear. There’s also some irritatingly unhelpful music, varying from drum ’n’ bass to jarring rap, which does Burgess’s poetry no favours whatsoever.

Unfortunately, neither do the performers. The intricacy and brilliance of the verse is utterly lost in speeches that trample all over the carefully crafted structure. The story survives, but its delivery dramatically undermines the possibilities that lurk tantalisingly below the surface of this Marmite production.

Nigel Barrett’s performance in the title role seems to sum up the whole paradox. He’s certainly got the swagger, the twinkle in the eye and the tenderness of Cyrano’s doomed romanticism, but his voice seems somehow flat and unvarying as he powers through vast swathes of potentially sparkling soliloquy at breakneck speed.

Cath Whitefield and George Potts emerge favourably as the object of Cyrano’s desire and his baker friend respectively, but this three-hour marathon could comfortably have been cut by a third to make it snappier, sexier and altogether more digestible.

* * *

April 9, 2015

Royal Theatre, Northampton, until Saturday April 25, 2015, then transfers to Northern Stage from Wednesday, April 29, to Saturday, May 16, 2015

THE story of the 17th Century poet-soldier with the whopping conk has proved popular in a multitude of artforms since it was first performed more than 100 years ago. Sometimes dubbed the most romantic play ever written, its theme of unrequited love and poignant tragedy tugs at the heartstrings.

Royal & Derngate have teamed up with Northern Stage again after last year’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof to produce this new version of Anthony Burgess’s 1971 clever rhyming couplet translation of Edmond Rostand’s French original. It’s a bold, ambitious production but for me, many of the directorial decisions – helmed by Northern Stage’s Lorne Campbell – seem strangely misguided.

Set unaccountably in a gymnasium in some indeterminate time period, the action plays out among monkey bars, sporting equipment and raked plastic seating. There’s a boxing ring-style microphone that’s used occasionally and randomly, and an ensemble of young supporting players are dressed, for some unexplained reason, in fencing gear. There’s also some irritatingly unhelpful music, varying from drum ’n’ bass to jarring rap, which does Burgess’s poetry no favours whatsoever.

Unfortunately, neither do the performers. The intricacy and brilliance of the verse is utterly lost in speeches that trample all over the carefully crafted structure. The story survives, but its delivery dramatically undermines the possibilities that lurk tantalisingly below the surface of this Marmite production.

Nigel Barrett’s performance in the title role seems to sum up the whole paradox. He’s certainly got the swagger, the twinkle in the eye and the tenderness of Cyrano’s doomed romanticism, but his voice seems somehow flat and unvarying as he powers through vast swathes of potentially sparkling soliloquy at breakneck speed.

Cath Whitefield and George Potts emerge favourably as the object of Cyrano’s desire and his baker friend respectively, but this three-hour marathon could comfortably have been cut by a third to make it snappier, sexier and altogether more digestible.

Joshua Jenkins as Christopher.

Joshua Jenkins as Christopher.

THE CURIOUS INCIDENT OF THE DOG IN THE NIGHT-TIME

* * * *

March 24, 2015

Derngate, Northampton, until Saturday, March 29, 2015, then tour continues

SO much more than a simple story about a boy with Asperger Syndrome, The Curious Incident has become a set text around the world as an entertaining literary classic. Mark Haddon’s novel has been thrillingly adapted for the stage by Simon Stephens and now, a couple of years after opening at the National Theatre, gets a UK tour.

Understandably, it’s been modified from its original in-the-round setting to allow for theatres such as Northampton’s Derngate, but the cleverness of Bunny Christie’s mathematically-based design is retained in vast walls of squared graph paper and algebraic projections to reinforce the story.

The narrative ostensibly hangs on the mystery of the grisly murder of a neighbour’s dog, and 15-year-old AS sufferer Christopher’s decision to investigate with the dispassionate clinicalism of his hero, Sherlock Holmes. When the emerging solution touches close to home – both literally and emotionally – it’s the study of how Christopher deals with this unfamiliar territory that forms the basis of the powerful drama.

Joshua Jenkins plays the dysfunctional teenager with considerable charm and likeability, tapping into the unpredictability but immense warmth of the character. Geraldine Alexander as his foil, the support worker Siobhan, provides a credible link between Christopher’s detached world and the real life that surrounds him, while Stuart Laing and Gina Isaac are both deeply moving as his parents, struggling with the problems he presents as well as with their own inner lives.

Marianne Elliott directs a rather brilliant staging, using lights, props, projection and physical theatre in every conceivable way to bring Christopher’s thought processes and rational logic into sharp focus. Occasionally the stunning technology is allowed to overtake the humanity at the heart of the story, but in the end it’s Christopher we’re rooting for, and the hugely optimistic final moments are uplifting and rewarding.

* * * *

March 24, 2015

Derngate, Northampton, until Saturday, March 29, 2015, then tour continues

SO much more than a simple story about a boy with Asperger Syndrome, The Curious Incident has become a set text around the world as an entertaining literary classic. Mark Haddon’s novel has been thrillingly adapted for the stage by Simon Stephens and now, a couple of years after opening at the National Theatre, gets a UK tour.

Understandably, it’s been modified from its original in-the-round setting to allow for theatres such as Northampton’s Derngate, but the cleverness of Bunny Christie’s mathematically-based design is retained in vast walls of squared graph paper and algebraic projections to reinforce the story.

The narrative ostensibly hangs on the mystery of the grisly murder of a neighbour’s dog, and 15-year-old AS sufferer Christopher’s decision to investigate with the dispassionate clinicalism of his hero, Sherlock Holmes. When the emerging solution touches close to home – both literally and emotionally – it’s the study of how Christopher deals with this unfamiliar territory that forms the basis of the powerful drama.

Joshua Jenkins plays the dysfunctional teenager with considerable charm and likeability, tapping into the unpredictability but immense warmth of the character. Geraldine Alexander as his foil, the support worker Siobhan, provides a credible link between Christopher’s detached world and the real life that surrounds him, while Stuart Laing and Gina Isaac are both deeply moving as his parents, struggling with the problems he presents as well as with their own inner lives.

Marianne Elliott directs a rather brilliant staging, using lights, props, projection and physical theatre in every conceivable way to bring Christopher’s thought processes and rational logic into sharp focus. Occasionally the stunning technology is allowed to overtake the humanity at the heart of the story, but in the end it’s Christopher we’re rooting for, and the hugely optimistic final moments are uplifting and rewarding.

Glenn Carter in the title role of Jesus Christ Superstar. Picture by Pamela Raith.

Glenn Carter in the title role of Jesus Christ Superstar. Picture by Pamela Raith.

JESUS CHRIST SUPERSTAR

* * *

March 16, 2015

Derngate, Northampton, until Saturday, March 21, 2015, then tour continues

IT’S a show that’s more than 40 years old and broke the mould when it came to guitar-driven rock musicals. Not only was its form the precursor to a whole generation of 70s and 80s creations, but its content was controversial in itself, putting the last week of Jesus’s life on stage with a screaming soundtrack of distortion and falsetto virtuosity.

The fact that Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber’s first massive success still has the power to move and impress says much about the quality of its writing. It may look a little dated in its naïve ideology, it may have long been overtaken in shock value, but it remains a landmark musical.

This new touring production from producer Bill Kenwright certainly looks the part. It has a monumental, facilitative design by Paul Farnsworth that is hugely imposing in scale and appearance. It also has a sizeable cast of enthusiastic young performers filling its nooks and crannies as adoring apostles or baying crowds, depending on requirements.

The highly experienced Glenn Carter – who’s played Jesus on Broadway – is relaxed and assured in the title role, and there’s particularly strong support from a rich-voiced Cavin Cornwall as the high priest Caiaphas and a fine understudying turn from Johnathan Tweedie as Pontius Pilate.

Elsewhere, pitching and control of Lloyd Webber’s ridiculously difficult score prove an issue for some, while Bob Tomson’s co-direction with Kenwright seems to lack some of his usual flair for the spectacular and the emotionally powerful. The overall effect is not helped by a worryingly mushy sound mix, awash with acoustically overpowering reverb, which gives the impression of the whole show taking place in a Turkish bath.

Musical director Bob Broad keeps the seven-piece band on their toes but it makes for a tough watch – and not just because of the subject matter. More clarity within the band and a much better mix to allow the vocals to be heard properly would make a huge difference to the ability of the production to reach the audience across the pit in the way that Tim and Andrew originally intended.

* * *

March 16, 2015

Derngate, Northampton, until Saturday, March 21, 2015, then tour continues

IT’S a show that’s more than 40 years old and broke the mould when it came to guitar-driven rock musicals. Not only was its form the precursor to a whole generation of 70s and 80s creations, but its content was controversial in itself, putting the last week of Jesus’s life on stage with a screaming soundtrack of distortion and falsetto virtuosity.

The fact that Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber’s first massive success still has the power to move and impress says much about the quality of its writing. It may look a little dated in its naïve ideology, it may have long been overtaken in shock value, but it remains a landmark musical.

This new touring production from producer Bill Kenwright certainly looks the part. It has a monumental, facilitative design by Paul Farnsworth that is hugely imposing in scale and appearance. It also has a sizeable cast of enthusiastic young performers filling its nooks and crannies as adoring apostles or baying crowds, depending on requirements.

The highly experienced Glenn Carter – who’s played Jesus on Broadway – is relaxed and assured in the title role, and there’s particularly strong support from a rich-voiced Cavin Cornwall as the high priest Caiaphas and a fine understudying turn from Johnathan Tweedie as Pontius Pilate.

Elsewhere, pitching and control of Lloyd Webber’s ridiculously difficult score prove an issue for some, while Bob Tomson’s co-direction with Kenwright seems to lack some of his usual flair for the spectacular and the emotionally powerful. The overall effect is not helped by a worryingly mushy sound mix, awash with acoustically overpowering reverb, which gives the impression of the whole show taking place in a Turkish bath.

Musical director Bob Broad keeps the seven-piece band on their toes but it makes for a tough watch – and not just because of the subject matter. More clarity within the band and a much better mix to allow the vocals to be heard properly would make a huge difference to the ability of the production to reach the audience across the pit in the way that Tim and Andrew originally intended.

Cameron Duncan as Bruno and Sam Peterson as Shmuel in The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas.

Cameron Duncan as Bruno and Sam Peterson as Shmuel in The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas.

THE BOY IN THE STRIPED PYJAMAS

* * *

March 3, 2015

Royal Theatre, Northampton, until Saturday, March 7, 2015, then tour continues

AUTHOR John Boyne’s book about an unlikely friendship between two nine-year-old boys is one of the publishing phenomena of the 21st Century. When the son of the Auschwitz camp commandant happens upon a young Jewish prisoner on the other side of the giant barbed-wire fence, his innocence about who he is and why they can’t play together offers dramatic irony by the bucketload, as well as a tragic denouement.

Adapter Angus Jackson uses this inherent tragedy to full effect in his stage version of the story, co-produced by the Children’s Touring Partnership, which had such success with its earlier adaptation of another wartime tale, Goodnight Mr Tom. The result is every bit as chilling as you might expect.

It’s given a thoughtful and well-paced staging by director Joe Murphy, employing a large revolve set from designer Robert Innes Hopkins to great advantage, while a monumental back wall of wooden slats and steel provides an imposing presence throughout.

Touring extensively to the end of June, an eleven-strong cast of adults gives the framework and backdrop to the unfolding story, while at its heart are the two boys, tenderly naïve and uncomprehending as their tiny tale of forbidden friendship puts into sharp focus the enormity of the horror that surrounds them.

In this performance, Cameron Duncan and Sam Peterson are highly accomplished as the commandant’s son and the Jewish boy respectively, learning and delivering vast swathes of text with understanding and considerable pathos. The entire weight of the drama is placed somewhat unfairly on their young shoulders, making the resulting admiration as much about their amazing feat as about the poignancy of the drama. For me, this casting decision actually takes something away from the power and importance of the play’s fundamental message, however impressive the children’s performances may be.

But it remains a piece of imagined history that fully reflects the truth of the nightmare that was the Nazis’ final solution, and it retains all the relevance of Boyne’s original book.

* * *

March 3, 2015

Royal Theatre, Northampton, until Saturday, March 7, 2015, then tour continues

AUTHOR John Boyne’s book about an unlikely friendship between two nine-year-old boys is one of the publishing phenomena of the 21st Century. When the son of the Auschwitz camp commandant happens upon a young Jewish prisoner on the other side of the giant barbed-wire fence, his innocence about who he is and why they can’t play together offers dramatic irony by the bucketload, as well as a tragic denouement.

Adapter Angus Jackson uses this inherent tragedy to full effect in his stage version of the story, co-produced by the Children’s Touring Partnership, which had such success with its earlier adaptation of another wartime tale, Goodnight Mr Tom. The result is every bit as chilling as you might expect.

It’s given a thoughtful and well-paced staging by director Joe Murphy, employing a large revolve set from designer Robert Innes Hopkins to great advantage, while a monumental back wall of wooden slats and steel provides an imposing presence throughout.

Touring extensively to the end of June, an eleven-strong cast of adults gives the framework and backdrop to the unfolding story, while at its heart are the two boys, tenderly naïve and uncomprehending as their tiny tale of forbidden friendship puts into sharp focus the enormity of the horror that surrounds them.

In this performance, Cameron Duncan and Sam Peterson are highly accomplished as the commandant’s son and the Jewish boy respectively, learning and delivering vast swathes of text with understanding and considerable pathos. The entire weight of the drama is placed somewhat unfairly on their young shoulders, making the resulting admiration as much about their amazing feat as about the poignancy of the drama. For me, this casting decision actually takes something away from the power and importance of the play’s fundamental message, however impressive the children’s performances may be.

But it remains a piece of imagined history that fully reflects the truth of the nightmare that was the Nazis’ final solution, and it retains all the relevance of Boyne’s original book.

Charlotte Wakefield and Ashley Day as Laurey and Curly in Oklahoma! Picture by Pamela Raith.

Charlotte Wakefield and Ashley Day as Laurey and Curly in Oklahoma! Picture by Pamela Raith.

OKLAHOMA!

* * * * *

February 25, 2015

Derngate, Northampton, until Saturday, February 28, 2015, then touring

REGULAR readers will be aware that five-star reviews are far from the norm for this site. A show really has to earn its accolade with a comprehensive package of performances, direction and creative teamwork. The fantastic news about this new production of the 70-year-old Rodgers and Hammerstein classic is that it thoroughly deserves the rating.

Much of its success is down to the sheer heart that is on display everywhere you look. Co-produced by the Royal & Derngate and Music & Lyrics, this tour shows no sign of stinting on costs or commitment, from the size of the hugely talented on-stage ensemble to the richness of the musical contribution from Stephen Ridley’s terrific band of ten in the pit.

Director Rachel Kavanaugh must take much of the credit for her clearly thought-out and delivered version of the always popular story of Midwest pioneer folk at the turn of the 20th Century. Of course she has those fabulous tunes to work with - including The Surrey With a Fringe on Top, Oh What a Beautiful Mornin’ and the title song itself - but it would be so easy to descend into corn as high as that elephant’s eye without a strong directorial vision.

One of the delights of this show is its depth across the board. From Charlotte Wakefield’s simply delightful Laurey, acting tough while secretly yearning for cowboy Curly, to the spirited rendition of matriarch Aunt Eller from the impeccable Belinda Lang, there’s not a crack in the whole joyful edifice. Curly himself is charmingly provided by Ashley Day, whose grin and warmth are more than matched by his vocal and dancing abilities.

Among the supporting cast, Lucy May Barker offers a mischievously entertaining Ado Annie, the Girl Who Cain’t Say No, who’s well matched with James O'Connell as her down-to-earth suitor Will. Gary Wilmot also puts in a well-judged comic performance as the pedlar Ali Hakim.

And lurking darkly around the edges of the sunny central plot is the disturbingly sinister figure of Nic Greenshields as Jud Fry, the misfit farmhand whose jealous obsession with Laurey threatens to derail her ultimate happiness. The combination of his imposing frame and stunning voice works to bring to life a characterisation of emotional power and genuine creepiness.

Drew McOnie’s fresh and inventive choreography, Steven Edis’s intelligent orchestrations and Francis O’Connor’s barn set also complement each other effectively, making a whole that is toe-tappingly greater than the sum of its parts, and deserves to win acclaim and audiences as it two-steps its way round the country between now and August. Yee-ha!

* * * * *

February 25, 2015

Derngate, Northampton, until Saturday, February 28, 2015, then touring

REGULAR readers will be aware that five-star reviews are far from the norm for this site. A show really has to earn its accolade with a comprehensive package of performances, direction and creative teamwork. The fantastic news about this new production of the 70-year-old Rodgers and Hammerstein classic is that it thoroughly deserves the rating.

Much of its success is down to the sheer heart that is on display everywhere you look. Co-produced by the Royal & Derngate and Music & Lyrics, this tour shows no sign of stinting on costs or commitment, from the size of the hugely talented on-stage ensemble to the richness of the musical contribution from Stephen Ridley’s terrific band of ten in the pit.

Director Rachel Kavanaugh must take much of the credit for her clearly thought-out and delivered version of the always popular story of Midwest pioneer folk at the turn of the 20th Century. Of course she has those fabulous tunes to work with - including The Surrey With a Fringe on Top, Oh What a Beautiful Mornin’ and the title song itself - but it would be so easy to descend into corn as high as that elephant’s eye without a strong directorial vision.

One of the delights of this show is its depth across the board. From Charlotte Wakefield’s simply delightful Laurey, acting tough while secretly yearning for cowboy Curly, to the spirited rendition of matriarch Aunt Eller from the impeccable Belinda Lang, there’s not a crack in the whole joyful edifice. Curly himself is charmingly provided by Ashley Day, whose grin and warmth are more than matched by his vocal and dancing abilities.

Among the supporting cast, Lucy May Barker offers a mischievously entertaining Ado Annie, the Girl Who Cain’t Say No, who’s well matched with James O'Connell as her down-to-earth suitor Will. Gary Wilmot also puts in a well-judged comic performance as the pedlar Ali Hakim.

And lurking darkly around the edges of the sunny central plot is the disturbingly sinister figure of Nic Greenshields as Jud Fry, the misfit farmhand whose jealous obsession with Laurey threatens to derail her ultimate happiness. The combination of his imposing frame and stunning voice works to bring to life a characterisation of emotional power and genuine creepiness.

Drew McOnie’s fresh and inventive choreography, Steven Edis’s intelligent orchestrations and Francis O’Connor’s barn set also complement each other effectively, making a whole that is toe-tappingly greater than the sum of its parts, and deserves to win acclaim and audiences as it two-steps its way round the country between now and August. Yee-ha!

Elizabeth Carter and Alex Beaumont as Laura and Bobby in Dreamboats and Miniskirts.

Elizabeth Carter and Alex Beaumont as Laura and Bobby in Dreamboats and Miniskirts.

DREAMBOATS AND MINISKIRTS

* * *

January 26, 2015

Derngate, Northampton, until Saturday, January 31, then tour continues

DREAMBOATS and Petticoats was the jukebox musical that introduced us to the members of St Mungo’s Youth Club at the dawn of the 1960s, borrowing the extensive Universal Music back catalogue to supply the live accompaniment to its gently entertaining story of young love.

Now the same team is back for more with a sequel, advancing the story by a couple of years to 1963 to take advantage of a new clutch of songs. The story’s as lightweight and unchallenging as before, with the music undeniably the selling point. Performed by the 16-strong cast, live on stage, it’s energetic, ably delivered and relentlessly designed to get your toes tapping.

The finest moments come with the beautifully arranged vocal harmonies, and there’s barely a foot wrong in the singing department, while musical director Michael Kantola leads the band with a tight sound through faithful representations of a host of hits, from Oh Pretty Woman to Venus in Blue Jeans.

Producer Bill Kenwright shares directing duties with musical supervisor Keith Strachan, with some memory-sparking choreography from Carole Todd, while writers Laurence Marks and Maurice Gran – of Birds of a Feather fame – pull off their usual trick of dialogue laced with witty gags and affable humour.

It doesn’t carry quite the same impact as its predecessor, maybe because the song list isn’t as strong. But for a harmless night of reminiscence to the accomplished strains of a bunch of talented youngsters, it’s dependably entertaining.

* * *

January 26, 2015

Derngate, Northampton, until Saturday, January 31, then tour continues

DREAMBOATS and Petticoats was the jukebox musical that introduced us to the members of St Mungo’s Youth Club at the dawn of the 1960s, borrowing the extensive Universal Music back catalogue to supply the live accompaniment to its gently entertaining story of young love.

Now the same team is back for more with a sequel, advancing the story by a couple of years to 1963 to take advantage of a new clutch of songs. The story’s as lightweight and unchallenging as before, with the music undeniably the selling point. Performed by the 16-strong cast, live on stage, it’s energetic, ably delivered and relentlessly designed to get your toes tapping.

The finest moments come with the beautifully arranged vocal harmonies, and there’s barely a foot wrong in the singing department, while musical director Michael Kantola leads the band with a tight sound through faithful representations of a host of hits, from Oh Pretty Woman to Venus in Blue Jeans.

Producer Bill Kenwright shares directing duties with musical supervisor Keith Strachan, with some memory-sparking choreography from Carole Todd, while writers Laurence Marks and Maurice Gran – of Birds of a Feather fame – pull off their usual trick of dialogue laced with witty gags and affable humour.

It doesn’t carry quite the same impact as its predecessor, maybe because the song list isn’t as strong. But for a harmless night of reminiscence to the accomplished strains of a bunch of talented youngsters, it’s dependably entertaining.

Mo Shapiro.

Mo Shapiro.

VICTORIA WOOD AND ME

January 17, 2015

Mo Shapiro, NN Café, Northampton

IT’S hard to make out who exactly it is that you’re reviewing in this one-woman tribute-within-a-tribute to the extraordinary talents of Victoria Wood. Performed with the blessing of the national treasure herself, it’s a cleverly woven collection of some of her sketches and songs into a production that’s a tour de force of memory and delivery, quite apart from its comic content.

Performer Mo Shapiro has dedicated herself to recreating Wood’s characters, mannerisms and infectious appeal, but neatly avoids the dangerous path of impersonation. Instead, she plays Gladys Winter, an endearingly pathetic woman of a certain age who claims to be Wood’s biggest fan. It’s Gladys who confesses her obsession with the star, to the point of learning her routines, monologues and songs by heart, and consequently being able to offer them up at the drop of a hat.

The device, with Gladys’s script contributions written by Louise Roche, works well in holding together an otherwise disparate collection of items in one complete piece. Without too much intrusion, Gladys supplies such wonderful Woodisms as Madeleine the gossipy hairdresser, the acid Sasharelle sales assistant and the crowning glory of those terrific songs.

Shapiro has an eye for her target’s visual tics – the tongue at the side of the mouth, the hand gestures – and an ear for her vocal intonations, while costumes and wigs leave you wondering at odd moments if she’s somehow channelling her idol. And with the sublime quality of the material at her disposal, it goes without saying that the audience has a ball.

January 17, 2015

Mo Shapiro, NN Café, Northampton

IT’S hard to make out who exactly it is that you’re reviewing in this one-woman tribute-within-a-tribute to the extraordinary talents of Victoria Wood. Performed with the blessing of the national treasure herself, it’s a cleverly woven collection of some of her sketches and songs into a production that’s a tour de force of memory and delivery, quite apart from its comic content.

Performer Mo Shapiro has dedicated herself to recreating Wood’s characters, mannerisms and infectious appeal, but neatly avoids the dangerous path of impersonation. Instead, she plays Gladys Winter, an endearingly pathetic woman of a certain age who claims to be Wood’s biggest fan. It’s Gladys who confesses her obsession with the star, to the point of learning her routines, monologues and songs by heart, and consequently being able to offer them up at the drop of a hat.

The device, with Gladys’s script contributions written by Louise Roche, works well in holding together an otherwise disparate collection of items in one complete piece. Without too much intrusion, Gladys supplies such wonderful Woodisms as Madeleine the gossipy hairdresser, the acid Sasharelle sales assistant and the crowning glory of those terrific songs.

Shapiro has an eye for her target’s visual tics – the tongue at the side of the mouth, the hand gestures – and an ear for her vocal intonations, while costumes and wigs leave you wondering at odd moments if she’s somehow channelling her idol. And with the sublime quality of the material at her disposal, it goes without saying that the audience has a ball.

Liliya Oryekhova and Talgat Kozhabaev in Moscow City Ballet's Giselle.

Liliya Oryekhova and Talgat Kozhabaev in Moscow City Ballet's Giselle.

GISELLE

* * * *

January 12, 2015

Moscow City Ballet, Derngate, Northampton, until Saturday, January 17, 2015, then tour continues

IT may not be as well known or as popular as Swan Lake or The Nutcracker, but the ballet Giselle has its own moments of sublime beauty and lyrical tenderness. Moscow City Ballet, touring their version alongside Swan Lake, deliver a fine interpretation with plenty to delight the ear and eye.

Musically, the two-act piece is performed by a generous orchestra, making a sound much deeper than its numbers should permit, with some careful direction from conductor Igor Shavruk. Adolphe Adam’s lush tunes and delicate orchestrations create a soundscape that’s fascinating and evocative.

And while the fairytale narrative may not be the most plot-heavy ever written – girl dies of broken heart when would-be lover is exposed as a two-timer – the dancers on stage make the most of their opportunities to impress.

Liliya Oryekhova plays Giselle herself, a winsome presence with emotional depth, while Talgat Kozhabaev and Artem Minakov compete for her affections with surefooted individuality. There’s strong support too from Ekaterina Tokareva as the queen of the ghostly corp of dead, broken-hearted young women betrayed by their loves. Some of the most elegant, moving passages come from the subtly affecting images this corp creates.

Artistic director Ludmila Nerubashenko continues the Moscow City Ballet’s tradition of bringing great classical ballets in the Russian style to audiences all over the world. In a wet Northampton on a Monday night in January, it’s an impressive achievement.

* * * *

January 12, 2015

Moscow City Ballet, Derngate, Northampton, until Saturday, January 17, 2015, then tour continues

IT may not be as well known or as popular as Swan Lake or The Nutcracker, but the ballet Giselle has its own moments of sublime beauty and lyrical tenderness. Moscow City Ballet, touring their version alongside Swan Lake, deliver a fine interpretation with plenty to delight the ear and eye.

Musically, the two-act piece is performed by a generous orchestra, making a sound much deeper than its numbers should permit, with some careful direction from conductor Igor Shavruk. Adolphe Adam’s lush tunes and delicate orchestrations create a soundscape that’s fascinating and evocative.

And while the fairytale narrative may not be the most plot-heavy ever written – girl dies of broken heart when would-be lover is exposed as a two-timer – the dancers on stage make the most of their opportunities to impress.

Liliya Oryekhova plays Giselle herself, a winsome presence with emotional depth, while Talgat Kozhabaev and Artem Minakov compete for her affections with surefooted individuality. There’s strong support too from Ekaterina Tokareva as the queen of the ghostly corp of dead, broken-hearted young women betrayed by their loves. Some of the most elegant, moving passages come from the subtly affecting images this corp creates.

Artistic director Ludmila Nerubashenko continues the Moscow City Ballet’s tradition of bringing great classical ballets in the Russian style to audiences all over the world. In a wet Northampton on a Monday night in January, it’s an impressive achievement.

For Northampton reviews from 2016, please click here

For Northampton reviews from 2014, please click here

For Northampton reviews from 2013, please click here

For Northampton reviews from 2012, please click here

For Northampton reviews from 2011, please click here

For Northampton reviews from 2010, please click here

For Northampton reviews from 2009, please click here

For Northampton reviews from 2008, please click here